One of the biggest single-day protests in United States history took place on Oct. 18. The “No Kings” marches, in which an estimated seven million people took to the streets nationwide to protest the policies of President Donald J. Trump, didn’t come out of nowhere: American citizens’ anger was spurred in large part by images of federal agents slamming down mothers taking kids to school, choppers landing on apartment buildings with naked children dragged out in the middle of the night, and the hallways outside immigration hearings becoming sites of physical altercations as folks were cuffed and arrested. ICE and border patrol agents had been wreaking havoc on American cities since the summer, especially targeting brown folks who may or may not be undocumented, with a strong “arrest first, sort it out later” energy.

When, starting in June 2025, protestors and border patrol agents clashed for 40 days in the historic downtown area of Los Angeles, Latino Theater Company founding artistic director José Luis Valenzuela recalled, “Everybody was freaked out, and people were deciding that they didn’t want to come to work. Our employees were saying, ‘I don’t want to come to work. Can I stay home?’ The answer was yes, because you could be arrested. City Hall is right here; all the detention centers were only nine blocks away. And we are all brown.”

In a year that Valenzuela hoped would be all about celebrating his company’s 40th anniversary and its legacy of Latino storytelling, his purpose had boiled down to one critical task in those summer days: serving as a caretaker for his fellow workers in a company in which having “Latino” in the name could make it an automatic target.

These fears are not new, of course. Nor is the history of Latino theatre persevering in spite of oppression, which dates back to the earliest days of the modern teatro movement, when Luis Valdez and striking farmworkers on a flatbed truck in California’s Central Valley in the 1960s told the story of the huelga (strike). El Teatro Campesino’s agitprop ethos—Valdez once described the company as combining “Bertolt Brecht and Cantinflas”—was aligned with the Cesar Chavez-led United Farm Workers Union through theatre and improvisation.

Latino Theater Company, founded in the mid-1980s, shares some roots with El Teatro but has pursued its own path, grounded in a similar attitude of resistance but in a different theatrical frame.

“We are rooted in Chicano theatre, and we pride ourselves in the professionalism of our shows,” said the company’s resident playwright, Evelina Fernández. “This may sound corny, but our work is not just based in professionalism but also in love and self-respect. We’re kind to each other, and we try to create a culture that is different from many places. We do continue to try and bring that family, love, and kindness into the theatre. I really feel like that’s part of it.”

Daphnie Sicre, an assistant professor in the department of theatre, film, and digital production at UC Riverside, who has directed plays at LTC, including most recently The Last Play by Rickérby Hinds, marveled at the company’s cohesion.

“When you have this incredible core of folks that have been working together for 40 years, that says something,” Sicre said. “One thing José Luis has done is he’s been able to enter rooms and spaces and speak for theatre, not just for himself, but for other people.”

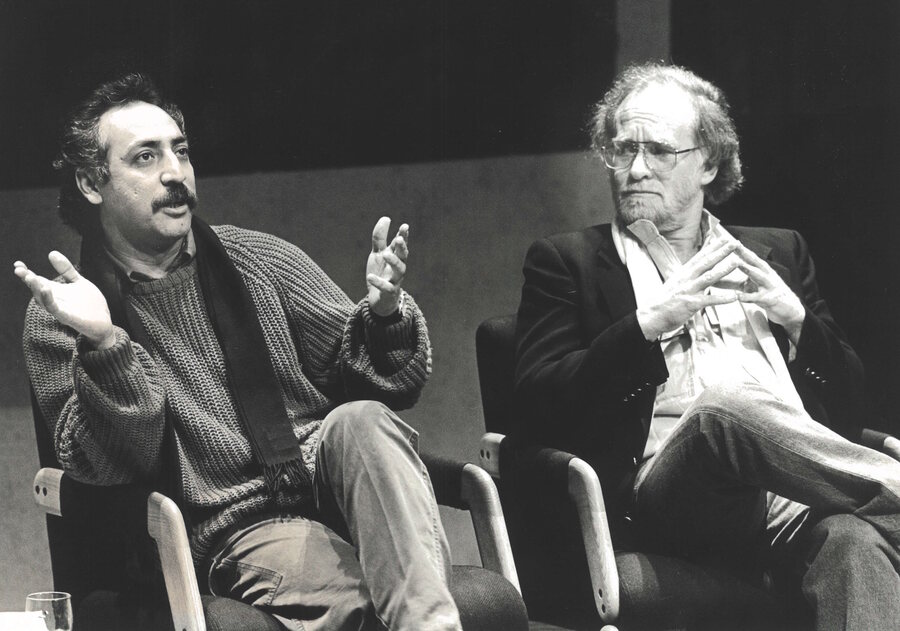

The core within the core of the company are Valenzuela and Fernández, who is also his wife. Valenzuela was born in San Francisco and raised mostly in Los Mochis, Sinaloa, Mexico, while Fernández grew up in East L.A. and was active in the Chicano movement of the 1970s and ’80s. Together with such fellow Latino talents Geoffrey Rivas, Sal Lopez, and Lupe Ontiveros, the couple formed Latino Theater Lab in 1985, and held meetings and workshop at the recently opened Los Angeles Theater Center, a city-funded venue built out within a 1916 bank building, and somewhat modeled on New York City’s Public Theatre. Bill “Bush” Bushnell, the artistic producing director, and Diane White, the producing director, took some of their leadership cues from C. Bernard Jackson, who had long headed the Hollywood-based Inner City Cultural Center, and who was an early champion of multicultural theatre.

“All three were committed way before anyone else, and for a very authentic reason—they wanted to build a theatre for Los Angeles,” Fernández said.

For six historic years, LATC hosted some of the most consequential theatre being produced anywhere, including work by Culture Clash, Reza Abdoh, and Sheldon Epps, among others. The center’s 80,000-square-feet were filled with as many 18 shows a season, and reached 25,000 subscribers. But that wasn’t enough to sustain the effort, and the Bushnell-White producing outfit shuttered in 1991, leaving the future of the center—and of the many companies it gave a home to—in limbo. It even led to a standoff in which the Latino Theater Lab occupied the building for 11 days, with result being that the LATC was declared a city-run rental facility, and the Lab found a new home at Center Theatre Group, where artistic director Gordon Davidson (an early commissioner of Valdez’s Zoot Suit, which gave Fernández her first professional theatre job) invited the troupe to become the beneficiary of the Latino Theatre Initiative, a five-year funding program designed to develop new commissions for CTG’s Mark Taper Forum.

When that program ended in 1995, the troupe finally adopted the name Latino Theater Company and briefly staged plays at a small theatre at East L.A.’s Lincoln Park, before returning to still functioning LATC, renting an office and a theatre for their production of Luminarias in the 1996-97 season.

When the city sought a new operator for LATC in 2003, the Latino Theater Company applied. After tense negotiations with a big developer, Valenzuela and his band of artists were named operator in 2006, receiving a 25-year lease and a $4 million grant to refurbish the historical building and funding committed to supporting the company’s programming, which has continued to blossom over the years.

Among their initiatives: the Circulo of Imaginistas, a five-year commission-oriented writing circle which looks to produce new works from both established and mid-career Latine voices, addressing timely issues and concerns. This particular collaboration pairs established playwrights with those who identify more as early- or mid-career, with the task of creating full-length plays over the course of a year.

Luis Alfaro, a playwright who is part of Circulo, has been a poet, playwright, and professor for the entirety of his career. Though this is his first official collaboration with the company, he’s been around the company and its artists long enough to recognize the company’s special sauce.

“Having an ensemble that’s been together for 40 years really does make the familial happen,” Alfaro said. “What is also really extraordinary is that, for lack of a better word, the audience is not a sophisticated theatre audience—not subscribers. It’s the community that’s coming. A lot of them have never been to the theatre before and that’s really exciting. Building theatre for people who don’t see theatre, building popular culture for people who don’t invest in the way we think of the traditional norm of investing is a really fantastic thing that José Luis has done there.”

Indeed, the company has modeled radical access with their $10 Thursday program, in which all shows on Thursdays cost just one Hamilton bill. Talking about that program brings Fernández to tears; she can barely say the number before her voice begins to tremble.

“Our audiences are working people, working families,” Fernández said. “You’re talking about families who have five kids and make $25,000 a year.” She expects them to show up for La Virgen de Guadalupe, Dios Inantzin, which is offered free. But to pay to see a play in a traditional theatre? Said Fernández, “They can’t afford to see The Nutcracker because those tickets are $100 each. That’s our audience, and I get emotional, because that’s who we do theatre for.”

The family feeling isn’t just reflected onstage and in the house but in the rehearsal room as well. Said Valenzuela, “It’s a big thing for our company and our theatre in this space: We don’t allow anybody to raise their voice here. In a rehearsal, no one is allowed to yell at or disrespect anybody. In every beginning rehearsal, I go through the first read-through with directors and designers and say that this is the law of the land.”

In addition to producing plays, many of them by Fernández (including her ambitious Mexican Trilogy), the company has also hosted large convenings, including a few iterations of the Encuentro Festival. The most recent, in 2024, saw 19 theatre companies and 165 artists from the United States and Puerto Rico gather and turn the center into a transformative cornucopia of Latino theatre for three weeks as it celebrated its 10th year.

Valenzuela is also especially proud of the National Latinx Theater Initiative, a regranting program that donates nearly $3.8 million to 52 Latino theatre companies across the United States and Puerto Rico.

“To me, that’s crucial,” Valenzuela said. “These companies don’t get any money from anybody. That is meaningful—really the beginning of something that can last 10 to 15 years and re-establish the ecosystem of Latino theatres around the country. Just having money to pay your director or your designers or your actors or your artists. That makes you feel a lot better about doing more work.”

Nurturing the next generation is on the company’s mind; Valenzuela, longtime head of UCLA’s MFA directing program, left that post in 2019, and though no one wants to think too much about it, there is an active succession plan to replace Valenzuela and Fernández, ensuring that the company will be around for many years after its founders move on to other projects. Valenzuela has no plans to stop directing or teaching, nor Fernández to hang up her profound pen.

Meanwhile the company and its space continue to hum along. Nearby shops and parking garages love when the company is bustling. Guisados Restaurant a few doors down certainly knows when one of their events is happening. Despite this past summer’s 40 days of chaos, it is the 40 years of community and collaboration that is the company’s real legacy.

Based in San José, California, David John Chávez is chair of the American Theatre Critics/Journalists Association and a two-time juror for the Pulitzer Prize for Drama, serving as jury chair in ’23. He is a regular theatre contributor to the San Francisco Chronicle, San Jose Mercury News, KQED and American Theatre magazine among others. Follow him on Bluesky @davidjchavez.bsky.social.

Support American Theatre: a just and thriving theatre ecology begins with information for all. Please join us in this mission by joining TCG, which entitles you to copies of our quarterly print magazine and helps support a long legacy of quality nonprofit arts journalism.