A pillow fight between two characters in separate cities, turning off the lights in two different places at the exact same time, throwing the ball in one part of the country and catching it in another—how much virtual rehearsal is enough to sync up moments like these, which would be much simpler to execute on a single stage? As colleges and universities around the country have shifted to virtual classes in the wake of COVID-19, theatre training programs are coping with the challenges of moving their rehearsals online.

Directors, professors, actors, and students all had to come up with answers quickly. “March 11 was when we found out that we needed to shelter in place for three weeks, but our executive director anticipated that it would be longer than that,” said Melissa Smith, conservatory director and head of acting at American Conservatory Theater in San Francisco. By March 30, the ACT MFA students came out of spring break ready to rehearse their first play, Roberto Aguirre-Sacasa’s Rough Magic, which is being rehearsed on Zoom, recorded as an audio play, and presented on Vimeo on May 6.

“There were technical glitches—somebody would get bumped out of a rehearsal, or somebody’s microphone wouldn’t work,” Smith said. “But improvisation is the heart of theatre.” Though she conceded that the physical theatre classes were among the hardest to teach online, within a week students reported that they had it all figured out.

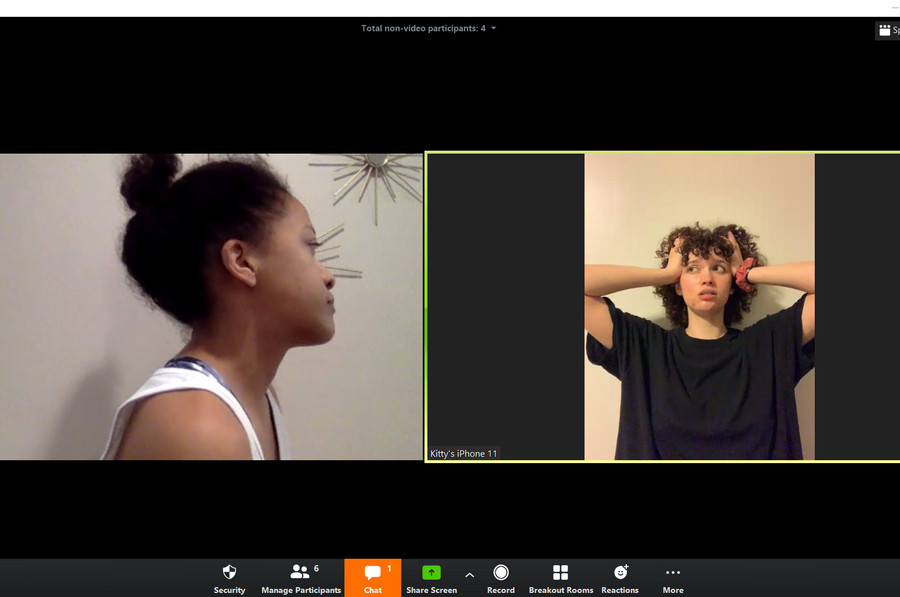

For many administrators, the very idea of converting Zoom rooms into classrooms and rehearsal rooms also took some figuring out. “Never in a million years would I have imagined plays being directed when everyone is in their own little squares,” said Risa Brainin, artistic director of Launch Pad at the Department of Theatre and Dance at the University of California-Santa Barbara.

Brainin has been working for the past 15 years with the Launch Pad, which is designed to fill the gap between readings and workshops on the one hand and professional premieres on the other. “We do these unique things called ‘Preview Productions,’” she said, “where we give the play all the bells and whistles of design but it stays in previews so the writer can continue to work.”

One of Brainin’s students, Daniel Blanco, who is trying to direct monologues from Libby Appel’s new adaptation of Chekov’s The Seagull and Aaron Posner’s own adaptation, Stupid F**king Bird, over Zoom. Blanco found himself struggling to set the tone for the room during their first rehearsal and working hard to not succumb to anxiety.

“If you have very low energy and you’re kind of sad, then there’s a big chance that your actors are going to feel the same way,” said Blanco, a fourth-year BFA acting student at UCSB who is also in the directing program. “I am trying to keep my own morale up.”

Students at Shenandoah University in Winchester, Va., had morale issues of their own when they learned that their production of Judith Leora’s The Hierarchy of Fish, produced with the Farm Theater’s College Collaboration Project, had shifted to the virtual realm. But Farm artistic director Padraic Lillis said online rehearsals provided an interesting push.

“The theatre doesn’t stop,” Lillis said. “I’m not going to say this new online platform replaces theatre, I just think that temporarily it is a really interesting form of storytelling.”

Adapting to the recent needs of continuing theatre while staying put in quarantine, Launch Pad is working on a “Zoom Festival,” which starts with a performance of Alone, Together on Saturday, June 6. About 75 people attended the first online reading of the piece, a compendium of scenes and monologues written by 24 playwrights during quarantine specifically to be performed on Zoom. “It wasn’t exactly live, but it’s the closest thing we have to live,” Brainin said. For example, one character throws an onion at another in a scene in a coffee shop; the two actors synced the throwing and catching so well that it looked for a minute as if they were in the same room.

“Things are curated as best they can be from what they have at home,” Brainin said. “It’s working with what people have, and then making choices.”

Like many others, Brainin had a hard time imagining how the chemistry between actors would translate to the screen, especially with everyone in a different physical space. After all, they are now looking at a picture of the person, not the actual person.

“The actors told me what’s different is that you’re getting a close-up of the other person,” Brainin said. “When you’re onstage, you’re not necessarily that close. You’re not right there looking at their face, which you are on Zoom.”

ACT’s Smith finds that the students in her acting class are enthusiastic about experimenting with how they can approach things from different angles. “They are finding it creative, and that’s what they care the most about,” she said. “It is an opportunity to still practice the craft that they’ve come to train for.”

And while Zoom cannot provide the group energy one feels upon entering a rehearsal room, Smith said this new configuration can make one aware of all the individual personalities.

“I find that the Zoom camera, like a film camera, is a magnifying glass,” she said. “When we’re working on a monologue or a scene, I read quickly how deeply, or not so deeply, connected somebody is to the material they’re working on. Sometimes in the classroom I have to let it go a little longer or look harder. I don’t have to look as hard here on Zoom.”

Sheila Correa, a third-year BFA student at UCSB who was part of Launch Pad’s reading of Fortunes by Dan Castellaneta and Deb Lacusta earlier this month, said she finds it difficult to look at the camera and simultaneously connect with the audience as well as her fellow performers. “As actors, we feed off of the audience,” she said, “but on Zoom we are not able to do that. It is now all about emoting as much on the face as possible.”

Even the most pedestrian physical actions need to be rethought entirely. If one character is asleep in a dorm room, for example, that character’s screen is on while the lights are off; then, when somebody else enters the room and turns on the light, the two actors have to figure out a way to turn on their lights at the same time.

“Since you are not in the same room, it forces the actors to really listen to one another,” said the Farm’s Lillis. “The play that’s happening this Sunday has a pillow fight scene. They have different matching pillow covers, but it is fun to watch the pillow go out of screen and then the other actor brings it in. The students were all game for that.”

Love scenes pose additional difficulties, he said, as do comedic scenes that lack the feedback usually provided by the audience.

“The idea of shared breath, of being in a live audience next to somebody, is not happening,” Lillis said. “The frustrating part every now and then is you wish you could be in the same room.”

Utkarsha Laharia is a Goldring Arts Journalism graduate student at Syracuse University.