Barclay Goldsmith, founding artistic director of Borderlands Theater in Tuscon, Ariz., died on April 3. He was 87.

Oh, Barclay Goldsmith, damn it. We have all been thinking you would die on us unexpectedly since the ’80s, and now you have gone and done it.

Barclay had serious asthma that brought him to our Sonoran desert in the first place. From the first day I met Barclay, and long before I knew of his diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease, I always worried about losing him. I’m not the only one who had this fear. It was a threaded conversation held over many years, in many cities and countries, across his networks of people—his gente. If you traveled on the road as a Tucson artist and could not give an update on Barclay’s well-being, you simply were not doing your job.

We would come home from a Borderlands Theater play and I’d ask my husband, Brad, if Barclay seemed okay. The anticipatory grief I felt foretold we would lose him suddenly. And we did: He’d gone to the hospital, improved, and then, inexplicably, was gone. The visceral feelings people shared about his time here in this mortal coil remained the greatest evidence that Barclay had his fist at once around our hearts and raised defiantly in the air: No justice, no peace! No human being is illegal!

Barclay lived a jam-packed life in his 87 years. He received a Master’s degree in Directing at Carnegie Mellon University, but as his wife of 63 years, revered historian Raquel Rubio Goldsmith, recalls, “He’d do anything to support his family.” That included a job at a car brake shoe factory in Pittsburgh and a stint at the mines in Southern Arizona driving a big truck full of dynamite—and that last gig came after he’d served as artistic director in the early days of Arizona Civic Theatre (now Arizona Theatre Company).

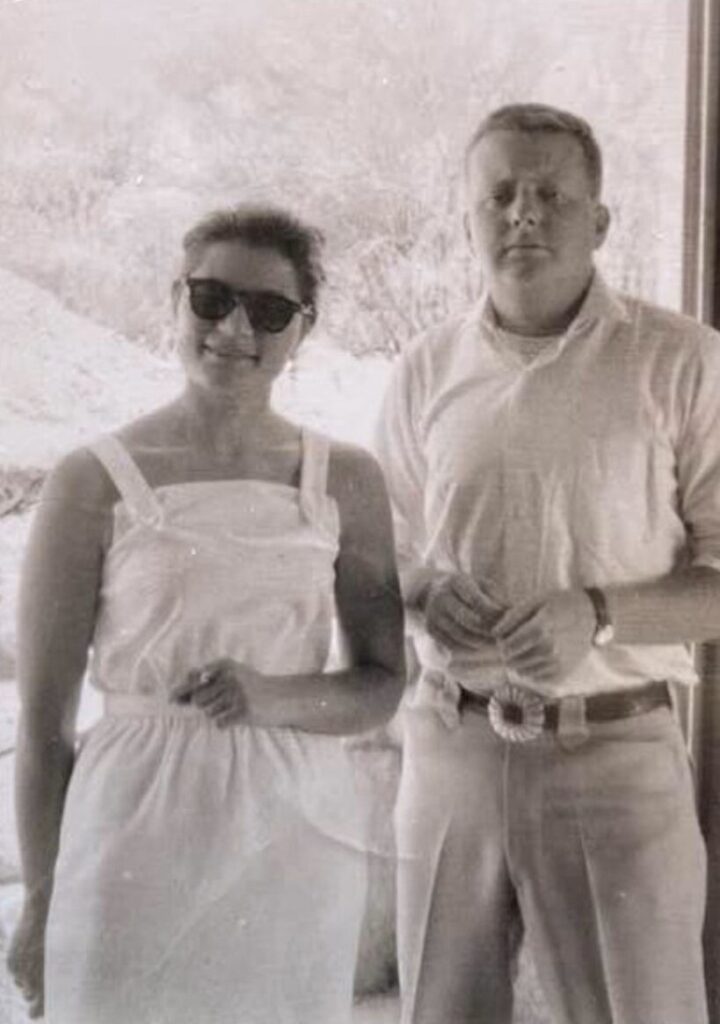

He and Raquel met shortly after he’d finished his degree in English at Stanford University. He’d taken a job as a journalist on the Arizona border at the Douglas Daily Dispatch. This was before he served as an assistant cultural attaché in Argentina in advance of that country’s Dirty War. He had friends who would later be counted among Argentina’s “disappeared.”

His father was playwright Clifford Goldsmith, whose work spawned the popular radio show Henry Aldrich. After the show moved to NBC television, Goldsmith stood by its star, Jean Muir, after she was accused of being a Communist and interviewed by the House Committee on Un-American Activities; General Foods pulled their funding from the show. While Barclay’s father was never officially blacklisted, his career was never the same. This was formative for Barclay. Injustice forges warriors. In this case, it also fashioned an artist. “Barclay just wanted a better world,” Raquel says.

In a rare fusion of politics and art, Barclay sought that better world through theatre. Barclay elevated the underdog, the immigrant, the unseen. His was a theatre of social justice, steeped in Brecht, commedia dell’arte, Teatro Campesino, and the San Francisco Mime Troupe, with whom he maintained a decades-long alliance. When he was part of Teatro Libertad, the San Francisco Mime Troupe actress Sandra Archer trained the members of the company. Later, in a recorded panel about Teatro Libertad, Barclay made a note about the confluence of Chicano theatre companies in Tucson: Those who started Teatro del Pueblo, he said, later formed Teatro Carmen and brought in outside theatres. He also acknowledged that Chuck Tatum had done a series of Mexican plays at the Tucson Historical Society. Said Barclay, “It takes all these currents to build a theatre movement…they need to be recognized.” Later, when Barclay founded Borderlands Theater, he brought along such Teatro Libertad veteranos as Silviana Wood. The roots were strong and deep.

To be recognized by Barclay Goldsmith was to be anointed by an international figure who had strong opinions born from an incisive mind. He was a brilliant producer, talent identifier, and nurturer of the downtrodden. He’d match artists together from across the country and across the border. If you were oppressed, he was your defender. If you lived on the margins of society, Barclay was your man. If you were an immigrant, Barclay made space for you on the page and on the stage.

An unindicted co-conspirator from the Sanctuary movement indictments of the mid-1980s—the Spanish-speaking informant couldn’t remember Barclay’s unfamiliar name—Barclay spent time on both sides of the border assisting migrants and fighting for human rights. He hid folks in his truck and his home. Nuns in Mexico worried he might have a fall, as he continued to volunteer even while advancing in age. His given first name was Charles, and the Mexican nuns called him Carlitos. To a white man with a Chicano heart, the sweetness of that diminutive nickname must have been worth the risk and the drive.

Recently, after a makeshift vigil for Barclay at our local shrine, El Tiradito, I joked with myself, “If you were to write something about Barclay, it would be 80,000 words.” We were an epic book, not a Facebook post. I assure you I’m not the only one who feels that way. Barclay would wait before speaking as if collecting his thoughts into one giant swirl. And when he delivered a pearl of wisdom, you held onto it. There were no forgotten conversations or memories. I remember standing outside before a play at Pima Community College and looking up at the sky, at the forming clouds, with Barclay. That sky played a role in his exit: He went with the eclipse.

Tucsonans laud El Tiradito as sacred ground, which is ironic because it is unconsecrated ground, a sinner’s shrine. The Coalición de Derechos Humanos activists have used the site to remember migrants who have lost their lives crossing our desert for about 25 years. These same activists, such as Isabel Garcia, the coalition’s co-founder and former Pima County Legal Defender, often spoke on panels before and after Borderlands’ plays, which delivered intelligent perspectives and analysis of the failures of politics and the law.

Fittingly, Barclay’s pop-up vigil was folded into one of their remembrances. Barclay’s church influence happened during a time when the alliance between God and art had more to do with the Sermon on the Mount than the Second Amendment. It reflected a God of ethics, not retribution. He told me more than once about a fellow volunteer who was actually an infiltrator, a spy who had penetrated the Sanctuary movement centered around Tucson’s Southside Presbyterian Church. Barclay understood that injustice, like justice, plays the long game. So we have to remain vigilant. And we have to create theatre.

I snuck over at sunset to El Tiradito to light a candle for Barclay the night prior to the vigil. Area legend holds that if a candle lit at El Tiradito at sunset burns through the night, your wish will come true. When I realized my candle had kept burning through the night, I tripped over another candle on my way to tell my husband, Brad, and splattered white wax all over my black work pants. That’s us in Tucson: knee-deep in candle wax, eking life out of a desert, making deals with spirit, saints, or justice itself—whoever will listen—and saying goodbye in sacred places in desecrated barrios on the edge of downtown. White-washed histories with brown bones. This place is stories layered upon stories layered upon stories if you dig.

Barclay saw all that and sought to capture it in his work. He believed our border had a story worth telling, worthy of the global stage. The last play Barclay saw of mine was called El Tiradito, performed at the same site. It had been commissioned by and starred his theatrical daughter, Alba Jaramillo (Teatro Dignidad), with his long-term collaborator, Alida Holguín Wilson-Gunn, directing. He lit up when he saw us working together.

Everyone who knows Barclay knows he was writing his memoir when he died. Raquel tells me he had just organized his papers shortly before he passed. Barclay kept starting his memoir over and over again. I and Eva Tessler, his longtime associate artistic director, both told him that if he kept rewriting the beginning he would never finish. The last time he talked to me about it, I encouraged him to just get out a rough draft and worry about the rest later. He told me, “I’ve got my process and you’ve got yours.” I wish I had not lost that round. Now we stand amid the stardust, attempting to capture the comet that was Barclay’s life.

If Barclay committed to your play, he really worked to find the right team. He had a keen producerial eye and instinct for talent and sensed what a playwright might need. I remember in the first reading I had at Borderlands with Refugees, a play I had written during my MFA at UC Davis, he brought José Cruz González from California to direct. It was the first time I had had a Chicano director work on one of my plays. It was the first time that I sat at a table in rehearsal that also felt like a table in my kitchen. Barclay was also the first person to commission my work. The play, Walking Home, was to be a collection of women’s voices on the border. He had spewed a bunch of names of people at me who he thought I should talk to, and one of them handed me a bunch of books. I studied those books for hours; it was at a time when I felt more comfortable in a library than a conversation. At some point I realized Barclay was not going to produce the show. I was devastated. I fired the play off to a national competition, the Chicano/Latino Literary Prize. It won first place. Some might say that when Barclay kicked me out of the nest, it began my national career.

If Barclay gave you even a secondhand compliment, you would carry it for the rest of your life. One of my favorite Barclay moments was back in the early days, before Barclay had produced my work, when Frank de la Cruz led the literary office and Barclay reported to me that Frank had told him, “Someday Elaine Romero is going to win the Nobel Prize and she is going to curse Borderlands for not doing her work.” I loved that he told me that story, and that it was the Nobel—we Chicanos have to embellish a little to make a point.

Barclay understood community like few others. He used every ounce of privilege he had in the world on behalf of us. Eva Tessler says he loved walking to rehearsal in Mexico City, where he had access to the highly trained actors of the day. He admired the work of such Mexican writers as Victor Rascón Banda, who you will hear referred to as Rascón Banda. He turned to Tessler, a multi-hyphenate translator and choreographer, to translate the plays into English. She translated at least 10 plays for him, often collaborating with El Círculo Teatral, often bringing Victor Carpinteiro to Tucson to perform.

Borderlands had an unspoken ensemble of veteranos and more recently trained actors, Pima grads, non-students, immigrants, and community members. Barclay committed to this network of artists, refining their talents, giving them multiple roles, having them direct, and requiring they rock a play monolingually in English and in Spanish on alternating nights. I can feel my neurons firing just thinking about it. He’d take the greenest actor in the world and give them a shot. Sometimes we’d be aghast: Where is Barclay finding these actors? But he was a true teacher at heart. He saw something in them that others didn’t see. He never held having an accent against an actor. He was far ahead of his time, working with an actor’s natural voice. He understood that having accented English meant you had two worlds living inside you. He celebrated that.

The actors worked in the office and always took care of the huge net of affiliated artists. We were Steppenwolf without the titles or, perhaps, the power. I remember back when he was producing at the historical Teatro Carmen (the oldest Spanish-language theatre in the United States), a place where the shows merged with the history of the place. It was there I saw the production of Milcha Sanchez-Scott’s Roosters (the text of which the troupe found in American Theatre), starring a 16-year-old Michelle Navarro. She now calls the experience life-changing. We all felt so at home at Teatro Carmen, which was inclusive before its time. Then one day, Barclay told me that a beam had fallen into the audience area; it was a miracle no one was hurt. It was his way of breaking it to me that we had to flee again, like refugees, in our own town.

His office was always filled with brilliant, often Latine women: Adriana Valenzuela, Marisa Grijalva, Annabelle Nuñez, Debra Padilla, Toni Press-Coffman, Suzi List, Alida Holguín Wilson-Gunn, Tessler. Nuñez says he would have run to the main post office to haggle a 11:59 p.m. timestamp on a grant. Raquel remembers that Barclay would stay up until 3:00 a.m. writing grants, then be up early the next morning to teach at Pima Community College, where he and Raquel were both founding faculty members. Barclay’s first associate artistic director, Chris Wilken, reminds me how groundbreaking it was at the time to have a professional theatre company in residence at a community college. Regina Romero, who at about 19 starred in my inaugural reading of The Fat-Free Chicana and the Snow Cap Queen, is now the kick-ass mayor of my town. Artists of color talk about Barclay finding them when they were young, broken, undocumented, uncastable, and brown. And then we would all watch them step into their power. He did it for me: The play of mine he premiered, Barrio Hollywood, was the first play in Samuel French’s history published in both English and Spanish acting editions.

He brought Diane Rodriguez in to direct Latins Anonymous and William Virchis to helm Real Women Have Curves. Shows sold out. (Valenzuela told me she had to reprogram the answering machine because Barclay was always holding up the phone line to check on that night’s reservations.) He received an NEA grant with Luis Alfaro and took great pride in developing Alfaro’s Greek plays. He made sure people knew that the work began here; if anyone got that narrative wrong, it would irk him. I once got into trouble for saying the plays had started elsewhere online. Barclay wrote me back, “Elaine, you know those plays started at Borderlands. Why would you say that?” The only problem was that it was a different Elaine who’d made the claim. Still, it took him a long while to forgive me. Oh, Barclay.

Barclay adored his National New Play Network (NNPN) community, of which he was a co-founder. Networks have always existed in Chicano theatre where people have always shared plays like contraband. Barclay often schemed with his Minneapolis counterpart Jack Reuler, former artistic director of Mixed Blood. Barclay’s involvement with NNPN elevated his every dream to the national scale, and in those early days, I’m not even sure if the most optimistic visionary could dream what the organization would become. NNPN deeply feels this loss.

Raquel tells a great story about an Argentinian theatre friend of Barclay’s who survived the Dirty War. When he went to attend this friend’s play in Buenos Aires, Barclay sent a note to him backstage. In turn, his friend got onstage to announce that the great American director Barclay Goldsmith was in the audience that night, news that was met with thunderous applause. “That meant so much to Barclay,” Raquel says.

As I talk to his wife Raquel at their kitchen table, I see a cell phone sitting next to her and one next to me. I wonder if it is his. I wonder if he was waiting for our calls. The last time I saw Barclay was a few months ago. He was sitting in a chair, in his requisite white guayabera shirt, and I was standing in the dirt, as we in Tucson are wont to do. I leaned over him and looked him straight in the face and said, “I love you, Barclay.”

I want to offer that moment to you, if you loved him too, to have your love heard through the vehicle of that moment, the past which is present, which is future, for him also to hear your love, for you to lean in with me, and through the potent power of theatre, which is both ephemeral and eternal, know that this bond we feel with our mentor, friend, fellow traveler, remains everlasting.

¡Barclay Goldsmith, presente! QEPD.

Elaine Romero (she/hers/ella) is a Chicana playwright. She is the playwright-in-residence/director of the National Latine Playwrights Award and Festival at the Arizona Theatre Company. Her plays include Wetback, Mother of Exiles, Title IX, Barrio Hollywood, Graveyard of Empires, Like Heaven, and Secret Things among others. She is an associate professor in the School of Theatre, Film, & Television at the University of Arizona, where she teaches playwriting and dramaturgy.