In the simultaneous use of the living actor and the talking picture in the theatre lies a wholly new theatrical art an art whose possibilities are as infinite as those of speech itself. —Robert Edmond Jones (1929)

Knowledge of the technical makes creativity possible. —Josef Svoboda (1968)

What is the greatest challenge facing theatre as we know it today—and, more important, as we dream it? Daunting ticket prices in a wobbling economy? Perhaps. Divides across class, and among cultures? Maybe.

Or is it the aging of the audience for live, serious-minded performance? Let’s say that is it, for the sake of argument. How are we to transform the theatre to attract young audiences, in this time when live performance could not be more important as a platform for much-needed social discourse?

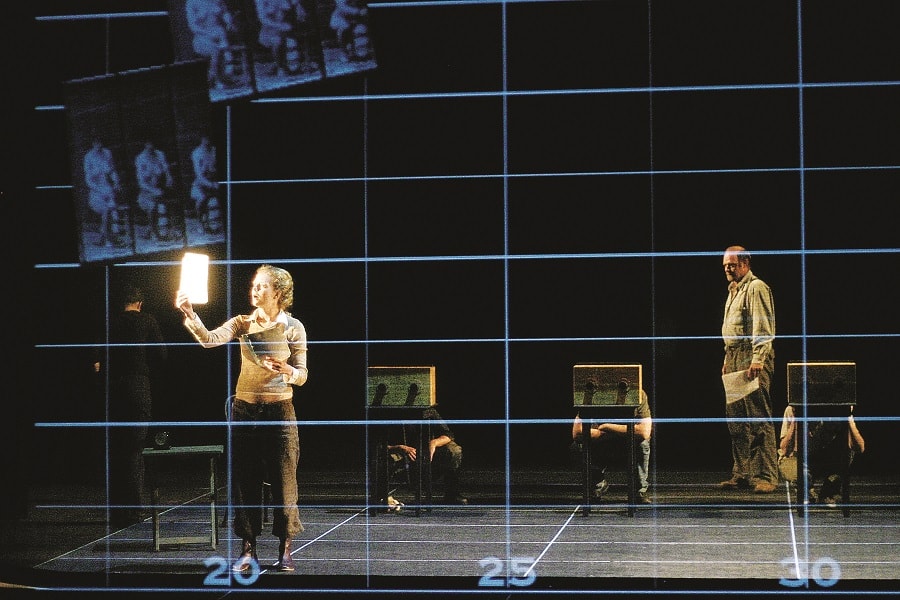

One answer to the question is to embrace the technosphere in which the youth of today are immersed (along with, of course, the rest of us not-so-young, yet nevertheless immersed), and to engage it passionately, while attempting to maintain a critical distance. This means opening the theatre’s stage door to projection designers, new media artists and systems engineers—to animators, filmmakers and laptop wizards—and to the panoply of technologies they practice.

In 1999, we founded the Multimedia Performance Studio at George Mason University in Fairfax, Va. Our goals were to explore new directions in the deployment of new technologies in the performing arts; to form cooperative connections with other like-minded artists, scholars and theorists; and to experiment with learning and teaching methods that would encourage students (and all collaborating artists) to discover how to make a new kind of theatre—theatre that explores and expands the rich possibilities of new-media scenography.

Old “New Media”: A Paradoxical (Pre-)History

The teaching of new-media projection is, in some ways, a matter of paradoxes and ironies. What we call “new media” are in fact old media—one might even say, the oldest media. (The wryly titled anthology New Media 1740–1915, edited by Lisa Gitelman and Geoffrey B. Pingree, is enlightening as to how new media becomes old media, and then becomes new again.) When we project images onto actors’ bodies and their environments, we have ancestors, even a history—in cave paintings (an early instance of, and mirror to our own, visual culture); in all-night outdoor Balinese and Indian shadow-puppet theatre; in the multimedia awe machine that was the medieval cathedral (with its backlit stained glass, looming vaults, ritual props and costuming, ghostly voices, breathtaking acoustics and drifting incense); in Mystery Plays, Jonsonian masques and Swiss automata; and in the 19th century’s dioramas and panoramas, stage magic, tableaux vivants and arcades.

As we approach the 20th century, we find Vsevolod Meyerhold (and his student Sergei Eisenstein) creating kinetic, cinematic, montage theatre with Cubo-Futurists and Constructivists in Moscow; in France, Jean Cocteau and Antonin Artaud exiting Surrealism to lay cinematic and theoretical foundations for future new media; and, perhaps most important, Erwin Piscator (while training Brecht) more or less inventing Epic projection theatre in Berlin. In the U.S., Piscator’s methods were adopted fruitfully by the Federal Theatre Project’s Living Newspaper, but this old version of “new media” evaporated, as did the German, French and Russian work, in the face of World War II.

In the 1950s (as he had earlier and more quietly in the ’20s), designer Robert Edmond Jones prophesied a theatre form that would interweave live performers and film—he called it “The Theatre of the Future.” In post-WWII Prague, Josef Svoboda embarked on a career that would come to epitomize the notion of “scenography”—creating, as he did, a unified approach to synthesizing scenic, lighting and projection design into a coherent (or at least manageable) whole, for theatre, opera and his Laterna Magika.

Emerging from the 1960s and ’70s, and working mostly outside the regional theatre, independent artists and companies began to revive approaches to interweaving the live and the projected. Mixing 8mm and 16mm film with slides and shadow play and video monitors, they evolved multiple approaches to making “new-media theatre.” These innovators include (to name just a few) Ping Chong & Company, Mabou Mines, Robert Whitman, John Jesurun, John Kelly, Julia Heyward, the Wooster Group, Laurie Anderson, Ridge Theater, Carbone 14, Guillermo Gómez-Peña, Anne Bogart, Impossible Theater, Theatre X, George Coates, Rinde Eckert, Snake Theater/Antenna Theater and Robert Lepage. Meanwhile, designers Richard Pilbrow, Boris Aronson, Ron Chase, Willie Williams and Wendall K. Harrington brought projection design to Broadway, Off Broadway, opera, rock concerts and regional theatre.

As new-media theatre’s constellation of the tools of projection design—show control systems and video projectors, animation software and hi-def flatscreens, 3-D stereoscopic display and infrared sensors—spiraled into the 21st century, a new stage practice began to come into its own, much as sound design had done some 10 to 20 years earlier, with sound sampling, wireless microphones, audio processing and multi-track recording. Ten or 20 years from now, projected imagery and new-media design will be as familiar a component of most theatrical practice as sound design is now. The emerging manifestation of a new area in performance design coincides with the proliferation of cell phones and iPods, text messaging and “social networks,” that comprise the lives of youth today, theatre’s future audience. With a new practice comes new teaching.

The teaching of set and lighting design has a rich and detailed history, but that of projection design is still being written. Not only are there budding artists wishing to enter the field of new media and learn its attendant theory and tech, but there are others studying theatre who can benefit from considering the field as well—directors, other designers, actors, composers, stage managers, producers and writers. (Artistic directors, and others who read a lot of contemporary scripts, point out that many writers are already writing new-media cues into their work, drawing on their own cinematic, televisual and online upbringings.) One set of players in the theatrical experience who may not need much training are young-adult audiences, who already want the kind of theatre new-media scenography can construct and offer.

Training for the incorporation of projection design into theatrical production calls for the discovery and development of new methods. The set and the performer are the surfaces on which projections fall—projections that are also a kind of light. These conditions encourage intensive collaboration and re-thinking of how the new and traditional design and production disciplines relate to each other, balancing harmonic coexistence with creative tension. There is no rule book, just a need to strive for precision and freedom simultaneously, in the learning, in the teaching, in the making, in the doing. There is no avoiding making it up, this new thing, as we go.

This learning by doing is in the throes of invention across the university and college theatrical landscape, where laboratories with roots (conscious or not) in the Wagnerian total artwork, the Gesamtkunstwerk, grope and lurch and burst into existence.

A Subjective Map of the (Teaching/Training/Learning) Field

Across North America, projection design is being taught, unsurprisingly, by working projection designers themselves. In the Design Department at the Yale School of Drama, Wendall K. Harrington teaches, in her words, “all the scenic, lighting, sound and costume design students, for whom it is mandatory, as well as stage managers, directors and even some students in the fine arts program. I am hoping to give seminars to the playwrights…soon.” One of Harrington’s MFA students, Sarah Pearline, recently created scenic and projection design for a mainstage show at Yale Repertory Theatre, Happy Now? by Lucinda Coxon.

Zachary Borovay and Maya Ciarrocchi have taught projection design for the Stage at Long Island University in Brooklyn, in an MFA program designated as New Media Art and Performance. At Arizona State University, in the Herberger College School of Theatre and Film, Jake Pinholster heads an MFA program in integrated digital media as well as one in performance design. Leah Gelpe has taught at Brandeis University, and Jamie Jewett at Brown University. Marc Downie, Shelley Eshkar and Paul Kaiser—the Openended Group—have conducted numerous guest residencies at the University of California–Irvine, Ohio State University and elsewhere.

Others—scenic designers, directors, choreographers, composers—teaching in the field of projection and new-media design approach it from a broader scenographic perspective. At the University of Kansas’s Department of Theatre and Film, since the 1990s, designer Mark Reaney, scholar/director/designer Delbert Unruh and their collaborators have forged marriages of live action and 3-D projection in the Institute for the Exploration of Virtual Realities (i.e.VR), staging experimental productions of Elmer Rice’s The Adding Machine, Mozart’s The Magic Flute, Sophie Treadwell’s Machinal and an original performance called Tesla Electric.

While much of the activity in projection design takes place at better-known schools with established theatrical reputations, many exciting research projects and experimental, stylized stagings occur at smaller institutions as well. At Gardner-Webb University in Boiling Springs, N.C., production designer Christopher Keene and director/writer Scot Lahaie recently assembled a team of student artists from their advanced stagecraft class to fill key production roles for an adventurous multimedia Shakespeare adaptation, LEAR ReLoaded. (This production is thoroughly documented in lavish book form.) In spring 2010 they will create a stage adaptation, employing projections, of Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451.

The University of Georgia’s Department of Theatre and Film Studies hosts a program in dramatic media; and the Departments of Theatre and Dance at UC–San Diego, and Drama and Dance at Colorado College, have recently created faculty positions in digital media, while the Department of Theatre at Michigan State University has created one in integrated performance media design. A job listing at Colorado College, in performance design, states, “A willingness to explore and experiment with new technologies and concepts of design media are essential to our program and to our educational mission.” While this is not an exhaustive list, these are some of the more forward-looking programs in the country.

In Canada, Josette Féral and Louise Poissant have created a center for new-media performance, Performativité et Effets de Présence, at Université du Québec à Montréal. In the Department of Film at York University in Toronto, Caitlin Fisher directs the Augmented Reality Lab. Composer Steve Gibson at the University of Victoria rehearses “telepresently” across the border, with new media artist/scholar Dene Grigar at Washington State University–Vancouver.

In the department of Theatre and Film at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, scenographer Robert Gardiner heads one of the most daring and sustained pedagogical explorations of new media for the theatre. With guest artists, students and faculty, he conducts research and creates stagings that employ projection not only as imagery and scenery but often as stage lighting as well. These productions, such as Studies in Motion: The Hauntings of Eadweard Muybridge (co-produced with Electric Company Theatre), have sometimes been showcased in Vancouver’s PuSh International Performing Arts Festival.

Outside the community known as “higher education,” training is also happening at art and media centers, and with theatre and dance companies. Foremost among these institutions is 3-Legged Dog at 3LD Art and Technology Center in Lower Manhattan, where Kevin Cunningham directs, produces and nurtures stage works incorporating a range of new media, including the revolutionary “Pepper’s Ghost” Eyeliner projection system. 3LD also offers residencies to guest artists and companies, and presents Moving Image Media Artists (MIMA) Workshops by Troika Ranch artistic directors Mark Coniglio (inventor of the Isadora show-control system) and Dawn Stoppiello.

Where from Here?

There is much to consider for theatre departments (and for regional theatres, opera companies and performance groups) in opening themselves to an unfolding aesthetic that comes toward us from the future, but has many roots in the past. Create faculty and staff positions in new media design. Form alliances with dance, music, visual art, filmmaking and animation programs; with puppeteers and computer scientists, engineers and critical theorists, film archivists and librarians. Come to grips with the need to invest initially in machinery and software for image creation, projection and show control—the first show’s not free…but the rest are cheaper. You then can transform the stage from a polar icecap to a Piranesi dungeon to a Brueghel landscape to the interior of a human brain, all with the cinematic application of cross-fades.

Bring projection designers in at the conception of the production, rather than as an afterthought. Embrace the idea of new media projection as a design area all its own, and not a subset of lighting or set design. Approach it in a visionary mode. Explore the montage aesthetic of audio-visual energy that pulsates at the core of our mediascape (use the machines to critique the machines). Incorporate storyboards and virtual theatre models to complement traditional drawings and tabletop set models.

In the spirit(s) of the Bauhaus and Black Mountain College, build ensembles of guest artists, faculty and students, in which innovative stage works are created collaboratively, drawing on the full range of scenographic innovations new media offer; and then those new media will become old media. And when even newer media appear, absorb them, keep working, and expect the next wave to arise any day now. It will. These media depict and reflect and emerge from the lives of theatregoers, who seek history, horror, satire and knowledge. If there are two things audiences want—to understand their world, and to escape it—maybe we, as practitioners of new-media theatre, can help them with both.

Writer/director/projection designer Kirby Malone and new-media scenographer/animator Gail Scott White are the artistic directors of Cyburbia Productions. They teach at George Mason University and are the editors of “Live Movies: A Field Guide to New Media for the Performing Arts.”