“I really don’t want to be onstage,” Skye Eiman (they/them) said to their sixth-grade English teacher during their first theatre experience, a rendition of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. “Can I have the role with the least amount of lines?”

And so a theatre technician was born.

Now 26, Eiman is a freelance, non-union general technician who works steadily in collegiate theatre, Off-Broadway, and Off-Off-Broadway. Or, to be more precise, who was working steadily in those realms until COVID-19 hit.

After operating the soundboard for the school musicals in seventh and eighth grade, Eiman went on to continue their love of performance through marching band in high school and studying percussion in college. They used their classically trained ear to their advantage when mixing the audio board for live productions.

After graduating from Christopher Newport University, they briefly did wardrobe at Busch Gardens in Williamsburg, Va., before booking a job at the Westchester Broadway Theatre in Elmsford, N.Y. as a dresser for Anything Goes. “That was decently short-lived,” they said, “because I found out I’m a lot better at audio than at sewing.”

They next transitioned to a technician role in audio after a colleague left before the theatre’s next production, Phantom. Suddenly Eiman was responsible for the upkeep of all microphones, monitors, and communication and audio systems.

The duties and responsibilities of a theatre technician can vary widely. In Eiman’s next such assignment, they were hired under the title of general technician for a dinner theatre but ended up working primarily as a kitchen assistant.

“I would be plating a dish,” Eiman said, “and the assistant stage manager would call me over and I’d go help move a prop piece or a set and then have to run back and get the next dish ready.” They did not last long in that role, as that is not the type of tech work they signed up for.

To Eiman, the life of a technician consists of trial, error—and figuring it out. They have dabbled in sound design in the East Village, as well as lighting, set building and design, and painting. Eiman studied music but worked with technicians who went to school for tech, alongside people who had been in the field for a decade.

“Theatre is a really, really accepting place a lot of the time,” they said. “But it’s also really, really intimidating because of how many people you meet who are so good at what they do.”

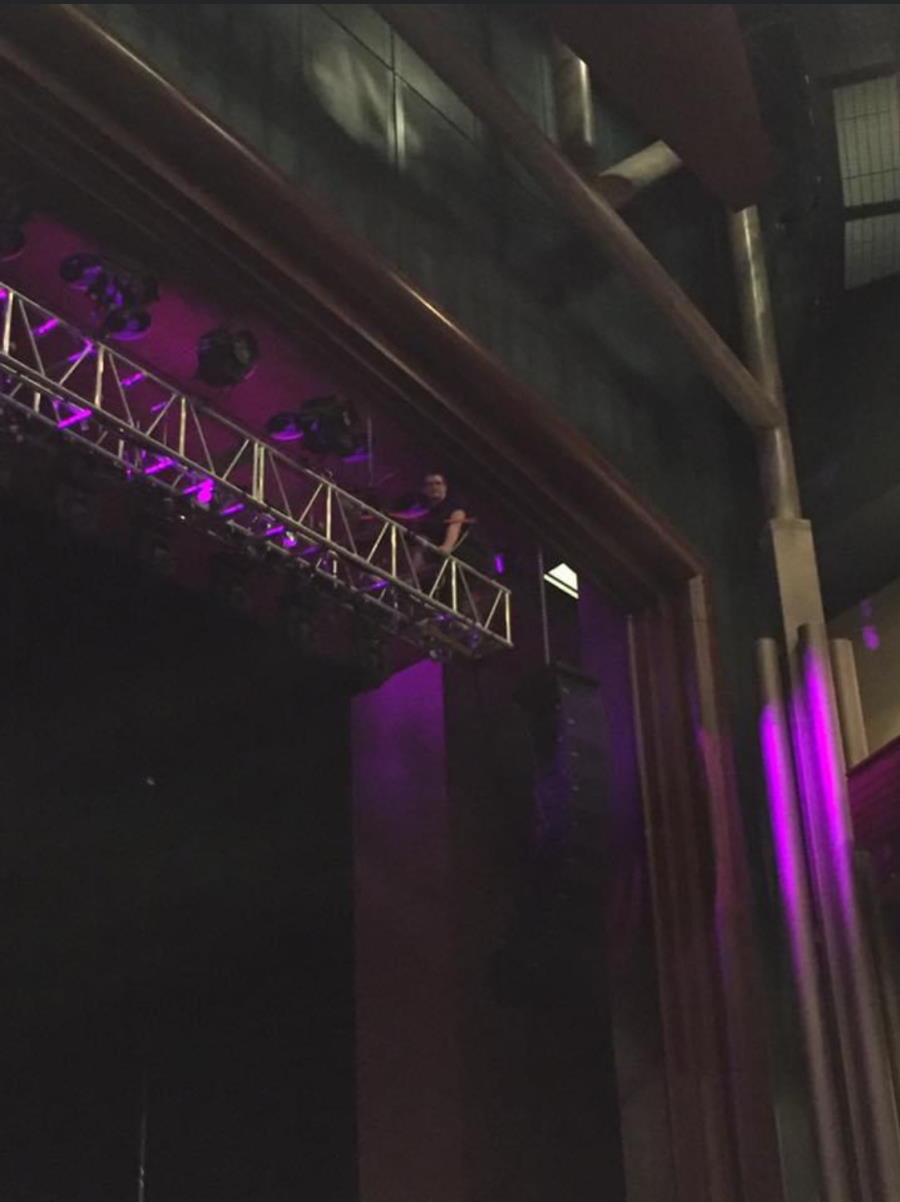

Though theirs is a mostly invisible role, great care goes into cleaning audio equipment, setup, rigging backdrops, the lighting grid, scenic pieces to move up- or offstage, and producing clear, level audio. “You don’t do this job because you want the limelight,” Eiman said. “Your job is to be hidden. If you’re seen by an audience member, you’re not doing it right.”

When COVID-19 hit, Eiman had just wrapped working on Forbidden Broadway. They had consecutive collegiate jobs lined up this spring at CUNY Queens College, Marymount Manhattan College, and Montclair State University, as well as freelancing for two different production companies. When all of these jobs were cancelled within four days of one another back in March, Eiman thought, “New York is not going to have any jobs for a very, very, very long time.”

Now, with Broadway’s reopening date pushed back at least to the beginning of 2021, Eiman doesn’t know what the future holds for anyone in theatre, let alone technicians.

“All these actors and technicians on Broadway are the best in the world at what they do, but even they can’t go six months without doing a three-hour production and be fine,” they said. “It’s still going to be weeks of rehearsals at that point to get used to doing things again. Weeks of dance rehearsals, blocking rehearsals, tech rehearsals, running lines, combat training—everything that goes into a production. It’s going to take weeks if not months at that point.”

During this great pause, some performers and productions have pivoted to online versions, but Zoom theatre doesn’t really have a place for most technicians.

“I was worried that I wouldn’t have a job until May,” Eiman said. “Then April hits and I’m worried I’m not going to have a job until the summer. Then May hits and I’m worried I’m not going to have a job until Christmas. And now I’m worried we’re not going to have jobs until 2021 or beyond.”

Until then, you’ll find Eiman in the back of an empty cargo van they bought back in January. It sat idle for months, first because they were busy working, then because they were afraid to go outside and work on it when COVID-19 was at its peak in NYC. But now it’s a work of art and a labor of love for Eiman, who is building it from scratch. Their plan is not just to travel in it but live out of the soon-to-be-camper-van, while they wait for the arts to return.

Victoria Mescall is a Magazine, Newspaper, and Online Journalism graduate student at Syracuse University.

This article previously used a different name for Skye.