Actor/playwright Chadwick Boseman died on Aug. 28 of colon cancer. He was 43.

Dear Chad,

As I prepared to write this letter, my last one to you, I decided to reread a text I sent you on back in February 2018, the opening week of Black Panther.

“You prepared your whole life for this moment,” I earnestly typed on my phone. “The moment in which folklore and Black beauty are used to change and transform the world. This is what we talked about, this is what we dreamed about way back when, and you went up and did it.” On the heels of what would become the biggest Black film of all time, you replied, “LOL, that’s right, Kam.”

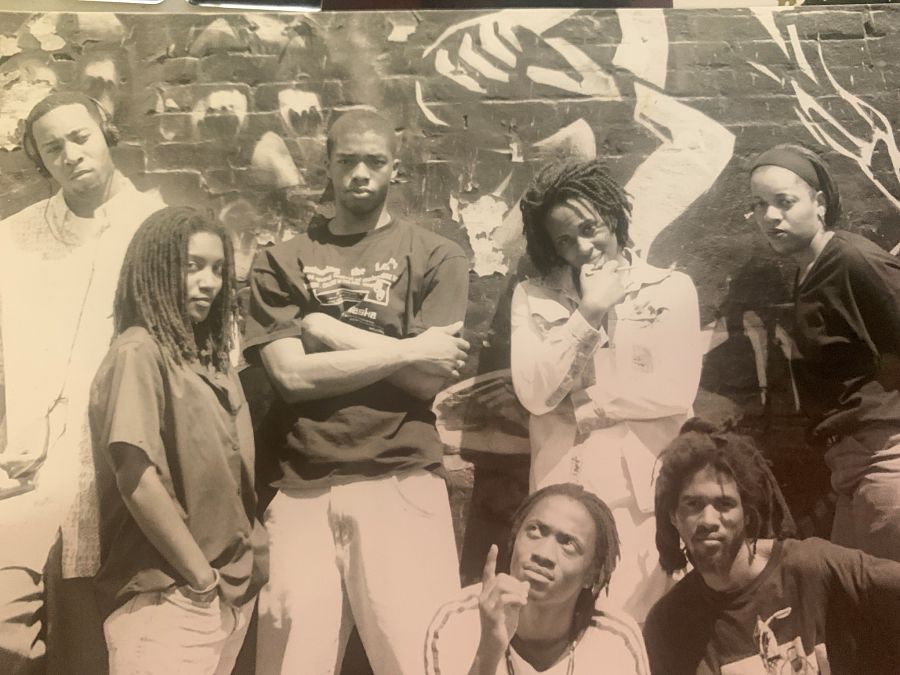

Do you remember when we met? I first saw you as a student at Howard University in the mid-1990s. We were both in a program called “Playwrights Lab” for artists interested in more experimental writing. We were both majoring in directing and we were all curious about the idea of “artistic possibility.” Back in the late ’90s, hip-hop gave us the permission to reinvent ourselves. You became “Aharon Sun of the Griots,” and I was “Kindred” (later to be known as Killa Kam). We were the generation defined by the boom-bap of Rakim, the poetic mastery of Lauryn Hill, and the political justice fight of Public Enemy. We dreamed of theatre having that possibility and the power to move the masses, the power to speak to a generation, and transform the world.

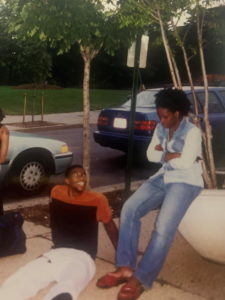

We learned In Playwrights Lab what we now know as devised theatre. But you—this young kid from South Carolina, spiritually grounded, family-centered, and curious about all things in the world, from Jewish and Christian faith to Egyptian mythology—yearned for something beyond plot and mere performance. I can see you in the hallway with incense always tucked behind one ear, a leather-bound book in one hand, and a half-chewed pen in the other, always ready to record, always observing. That was the writer and the director in you. In your satchel, an August Wilson play and a Bible. Your compassion for the world was infectious, your passion for creating new worlds even moreso. When we were roommates in Bedfort-Stuyvesant in the early 2000s, I would marvel at your discipline. I would hear the clickety-clack of your laptop at 3 a.m., only to find you up at 7 a.m., practicing tai chi in the kitchen. This is when I knew I would never cut it as a writer; one needs stillness and focus, all of which you possessed so effortlessly.

You would observe human behavior and chuckle at moments that many would find curious. But Chad, you also filtered the world through a cosmic lens—a lens that saw men as gods and recognized godly beauty in the mundane. Without question, you knew that Black people are divine. You always saw. You always felt, you always floated through the world with a self-assuredness, crooked smile, as in constant conversation with God and the Orishas. I think you could see the other side, as if by a conduit. Your writing told me as much.

In college, when we began writing Rhyme Deferred in 1997, you insisted that the character of Herc (inspired by DJ Kool Herc, godfather of hip-hop) represent the Yoruba of deity of Elegba, the god of the crossroads, choices, lessons. Herc you manifested on the page and in performance. Herc was the Godfather, the guide, the ancestor. We revered his character.

Hieroglyphic Graffiti became your work about graffiti art, and how it was a parallel to Egyptian hieroglyphs, coded graffiti scrolls as encoded messages for future and past generations to wrestle and reckon with their meaning. But more importantly, Graf as a symbol, a symbol of existence, scrolled on walls to say “WE WERE HERE.”

So many years later, you explored your lyrical prowess and shared your gift for spoken word and heightened language again in your play Deep Azure. This is the one that broke me wide open; it was a lyrical sonnet, written all in prose. You spoke of the character of Azure as a widow, suffering from bulimia, as through the course of the play we watched her physical body waste away as an allegory of the disease of racism that plagues our country.

Deep Azure was also the reflection of the death of our mutual friend and classmate Prince Carmen Jones Jr., gunned down by Prince George’s County police. As I write to you, Ta-Nehisi Coates and I have begun to work on a film to remember Prince. It is cruel to have to mourn you both at once; it is an act of love to remember you both. I am listening and still learning from you. What always struck me about your writing on Prince’s death is how much you insisted on exalting Black life.

Of course, this is what you always did with your acting. You could disappear into a role, without ego, in order to bring the fullness, the humanity, the magic of the characters to life. Fewer people know that you also did this in your writing. Producing your work meant that I had a front-row seat to your brilliance; being your friend meant that I had a brother who loved people like you loved your characters. I remember how easily and often you would share, “Love You, Kam.” Your love for life, family, and your community were the morals and values that guided you every day.

Because you lived on several planes, I sometimes heard your words as parables and riddles, many of which I am still trying to decode. I would like to think you meant it to be that way. Leaving us with lasting artifacts of your whisperings from the other side. Leaving us with a legacy of our the depth and beauty of Black brilliance.

This is the hardest letter I have ever written. I have lost a friend, a comrade, a brother in arms, but I know, if I sit still with my leatherbound book and incense, I can hope to hear your voice whispering back.

Chad, Aharon Sun of the Griots:

Dear brother, you have done all you dreamed of and more

Brother, you moved the masses

You spoke to many generations

Chad, you transformed our world.

Kamilah Forbes is executive producer of the Apollo Theatre, and was previously the co-founder and artistic director of HiARTS/Hip Hop Theater Festival.