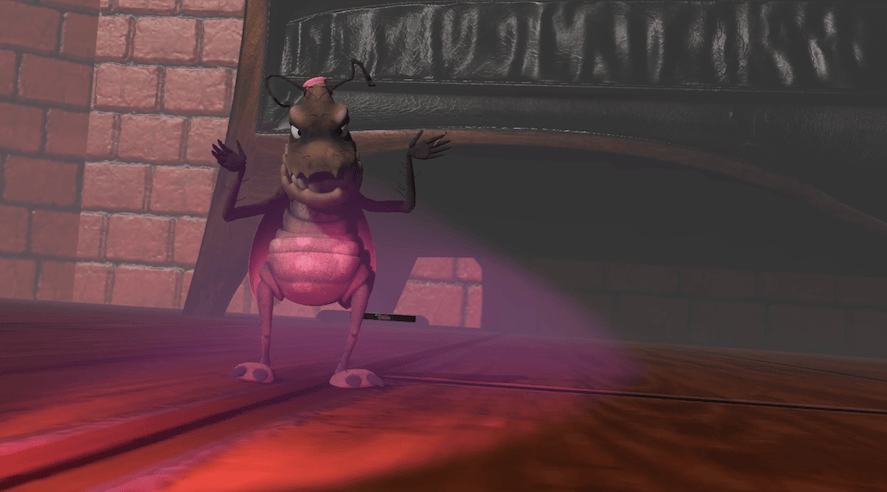

There’s one group of New Yorkers who aren’t contemplating a move to the suburbs: the cockroaches. In the six-part virtual reality play Crush, which premiered on YouTube, a Kafka-esque exploration of survival is told through the eyes of a roach.

Krista Knight’s Crush was first developed as an interstitial play presented between short works in the F*It Club’s 2019 Spring Fling Festival, but this story of a lonely cockroach riding out the dog days of summer in a studio apartment feels, well, very apt for the moment.

Selected as a finalist in the Samuel French Off Off Broadway Short Play Festival—an honor which means that Crush will receive publication and licensing—the play didn’t get a staging, as this year’s festival contenders were judged on scripts alone due to the pandemic. That got Knight—herself cooped up in her 500-square-foot studio—thinking about bringing the cockroach to the screen instead.

“This play felt like a good candidate to try out some of these tools and just go ahead and make something in a time that has been very hard,” says Knight, who performed the movements of the cockroach avatar with a VR headset (the results can be viewed via a normal screen). Inspired in part by the company Tender Claws, which brings theatrical storytelling to video games, Knight worked with longtime collaborator Barry Brinegar, and with Ben Beckley, who voiced the beatnik-inspired pest for Crush.

“Unintentionally, the cockroach emerged as kind of a metaphor or symbol of resilience and surviving, you know?” says Brinegar. “I think that’s what drives our collaboration: We’re both compelled to make work, for better or for worse. We’re just going to have to do it—no matter what happens.”

Knight likens the production process of Crush, in which she created the choreography in response to Beckley’s audio recordings, to the exquisite corpse method, in which images and words are collectively assembled. (She was also inspired by a particular vermin that took up residence in her bedroom.) With some New Yorkers fleeing the city, Knight concedes that she has felt a little left behind. “It really did feel like it was me, Barry, and this cockroach that we lived with,” she says with a laugh, noting that the play did get some updates in response to the current moment.

“Virtual reality is innately theatrical because it can be immersive and because it can be live—I think it offers a lot of tools that are really exciting to theatre artists and that can continue to enhance our vision,” says Knight. She hopes Crush can be available someday as a play that viewers can virtually experience in 3-D with headsets in real time.

Wiggling and dancing around as a bug, and exploring this new world of VR, has proved to be a positive creative outlet for the writer during this time of social distancing. “As a playwright and a sort of proselytizer of playwrights, there’s lots of opportunities for us to sort of be artist-entrepreneurs,” she says. “The more platforms that arise, the more opportunity there becomes to realize our vision.”

The current upsurge of virtual reality theatre is also providing out-of-work stage actors a creative outlet. Deirdre Lyons is straddling tech week and live performances for two VR theatre experiences, Tender Claws‘ The Tempest and Double Eye Studios’ Finding Pandora X.

The Under Presents is a virtual world of recorded performances full of magic for multiplayers that has been enchanting gamers who have Oculus and Rift headsets for more than a year. The Tempest, which will run through September, is the latest experience available on the platform and features live performances.

The show’s 11 actors are stationed remotely with Oculus Quest or Rift headsets and guide the viewers, who serve as Prospero’s spirits, through the virtual experience. In this adaptation, the pandemic has closed a playhouse and its production of Shakespeare’s The Tempest. The viewers must help the actor playing Prospero to perform the cancelled play in this new sphere. The action begins in the lobby of a shuttered theatre.

In this time of social distancing, Lyons says that audiences, which are capped at eight people, often become fast friends. The first scene is usually full of virtual hugs. “It’s kind of a strange thing where people will seek out connection and touching, especially now,” says Lyons. “There is that satisfaction of feeling like you’re giving another person a hug, and I think that’s a beautiful thing.”

Performances with viewers who are familiar with the universe of the Under Presents and know the world’s magic tricks are especially fun, she says. For example, one recent participant usurped the Ferdinand and Miranda scene by magically creating a new character, a plush dog named Buster. The magic-making extends to the actors too. “We can make a storm and lightning while we’re doing the show,” says Lyons, noting that a stage manager is always available during performances via Zoom for any disasters, weather-related or otherwise.

For Finding Pandora X—which just won the top prize for VR Theatre this week in the Venice Biennale Cinema against Jon Favreau’s latest project—the actors are aided by domain masters that trigger scene changes and special effects.

The VR experience is a modern take of the myth of Pandora, and viewers must help Zeus and Hera, the remaining gods of Mount Olympus, to recover Pandora’s illustrious box of hope to fix the unbalanced world. Audiences are tasked with solving puzzles together and navigating an escape room of sorts during the experience.

“We believe in collaboration and cooperation, so when people are having a social experience they’re working together to solve something—and that leads to something good,” says Kiira Benzing, the director of the show and founder of Double Eye Studios.

Benzing got her start in theatre and went on to write and direct non-traditional documentary films, some with immersive musical dance numbers. “I was making some of my documentary films and I felt like the linear format—this thing that’s inside a frame—doesn’t really fit my thinking as an artist, and as a trained theatre performer,” says Benzing. “The best thing that I could do was to make tangential companion pieces for my documentary films.”

Benzing’s nonlinear, interactive 3-D companion pieces eventually led her to found Double Eye Studios in 2009. “The thinking is different, because now you’re capturing the world instead of something inside of the frame,” she says of using a 360 camera. “But that makes total sense from all my theatre background.”

The company has a team of writers, developers, and coders to bring these stories together, but the world-building process isn’t complete without audience participation. “We really believe in players having a role inside the story, so we think of our audience as players,” explains Benzing. “That also goes back to theatre, because I love what the French do with that word jouer—to play, to act.”

In Finding Pandora X the players can talk, which adds an element of fun for the actors. “Audience members can talk, and we are encouraging them to do so,” says Lyons, who portrays Coryphaeus in Finding Pandora X. “It is quite exciting that the audience tends to participate. They like it, and it seems easier because there is anonymity.”

The players begin in the clouds, where the gods who have disappeared from Mount Olympus are represented by light pillars. Players ask the pillars for protection and guidance before their respective quests. Benzing plans to update this light forest scene with user-generated content, so that audiences can submit people and things that they’ve lost during the pandemic to shine on. In many ways, this unbalanced world in the clouds and the seeking of hope to restore it feel relevant to our current predicament.

While Double Eye Studios has been developing and producing interactive virtual theatre experiences for years, the pandemic has definitely changed the process. The shows are generally staged in front of live audiences with virtual elements for remote viewers, so technical teams were able to assist actors with headsets and rigs, and even to hold wires onstage so they wouldn’t trip. Now the actors have to learn how to install and run the machinery in their homes.

“They’re becoming these incredible troubleshooters and their own self-technicians to solve things,” says Benzing. “I think it’s really powerful that as an industry we’re saying, ‘You’re going to learn the technology.’ Now we have more skilled and super proactive actors.”

For her part, Lyons recommends that actors venturing into VR anticipate things not going right all the time. “You may lose your internet connection, you may push the wrong button or trigger something, you may even fall off of a building, but of course you won’t die!” she says with a laugh. “And that is where the fun starts—you have to troubleshoot your way out of it.”

The learning curve extends to the audience too. Lyons hopes that VR headsets become the norm, and that more theatremakers and fans will explore VR theatre experiences while live performances remain paused. Whether it is to watch a dancing cockroach, help to put on a production of The Tempest, or to find Pandora’s box, virtual theatre shows can provide a space to connect and commiserate in these trying times.

“[The headset] sort of does the suspension of disbelief or that magic circle for you, like all of a sudden you’re just another world,” explains Lyons. “You lose yourself in it, and that is magical—there’s a realness, and then there’s also a fantasy.”

Benzing is ready for the theatre industry to come play in these virtual spaces. “Those of us who have been creating in this space for years have just been waiting for people to join us here. We’ll continue to build seats for them, and we’ll just hold the seat!”