Why am I telling this total stranger about my tattoo?

I’m a fairly private person, but in my first 30 minutes on the phone with this woman, I’ve told her details of my childhood, my bedroom furniture, and greatest grief. I know about the birth of her son, the art in her office, her sense of self. Another half-hour later, she’s gone.

After a year of isolation and Zoom art fatigue, the feeling of Brooklyn theatre company 600 Highwaymen’s A Thousand Ways, Part One: A Phone Call was revelatory, an antidote to the exhausting, never-ending quarantine question: “How are you?”

“At first, we thought we were going to make a conversation between strangers,” said Michael Silverstone (he/him), who, with Abigail Browde (she/her), comprises 600 Highwaymen. But conversation, in turned out, wasn’t what they needed. “Conversation pulls us into behavioral mannerisms that are about politeness, and how we’re socialized to engage with someone,” Browde said. That getting-to-know-you, first-date chit-chat—what’s your name? what do you do?—keeps things pretty surface level.

“Connection is kind of an overused term,” Silverstone said. “But if I’m starting to understand who you are, what you care about, what you’re looking at, what you’re thinking about, what you come from—if you can connect the dots of those details, you can start to create a connection.”

So sitting on my bed in Seattle, I called an Arizona phone number—I’d booked my ticket through Arizona Arts Live, in Tucson—and was connected to my anonymous partner, wherever she may have been. I was A, she was B. Guided by automated, recorded voice prompts, we answered routine but revealing questions and completed simple, shared tasks, like counting. Later, as our auto-guide moved us from question-and-answer into a narrative, we rode together down a desert highway. I could see us so clearly in my mind. Then, we hung up.

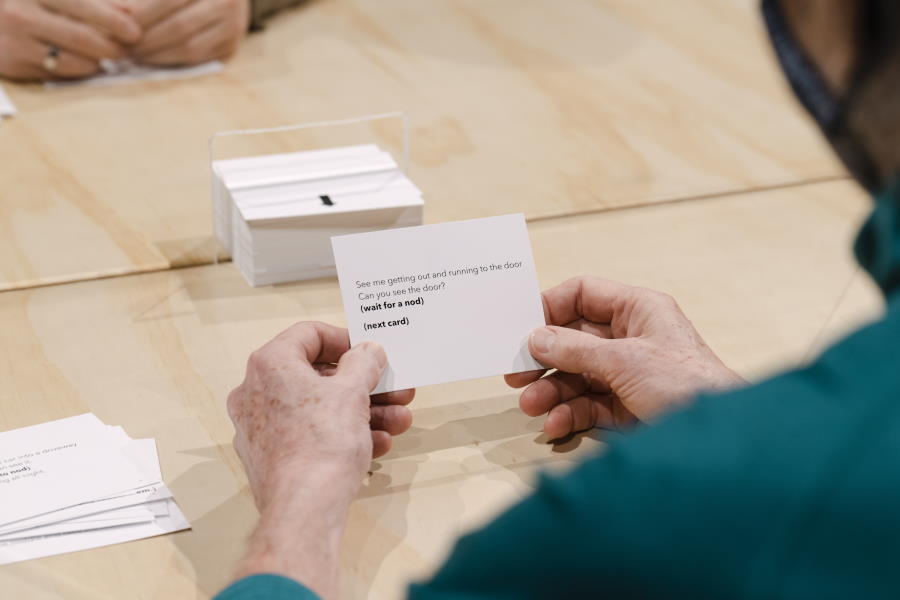

A Thousand Ways is, per its official description, “a triptych of encounters between strangers.” Part One: the phone call. In Part Two: An Encounter, two people sit across from one another at a table, separated by plexiglass, and follow instructions provided on a series of notecards. When the time safely comes, Part Three: An Assembly will gather participants in a theatre en masse.

In much of their work, 600 Highwaymen pull off the magic trick of capitalizing on, but not exploiting, the intimacy of strangers. With gentle but clear guidance, built on unsentimental honesty and un-self-conscious rigor, people who normally despise audience participation become convinced. And though theatre is fundamentally about pretending, 600 Highwaymen seems uninterested in pretending that the form’s more arbitrary rules matter. As the world reopens and we reacquaint ourselves with each other, as humans and artist-audiences, that guidance feels like exactly what we need.

Browde and Silverstone met in college and began making work together as 600 Highwaymen in 2009, the same year they got married. They’ve since toured their shows around the world, and critical praise from major outlets up to and including The New York Times has followed.

When talking about theatre, they’re scrupulously non-prescriptive, constantly reiterating that they don’t have answers or solutions—they’re just following their own curiosities.

Those curiosities eddy around ideas of collectivity and spectatorship, of dissolving arbitrary lines between artist and audience, “professional” and non. Employee of the Year starred 9- and 10-year-old girls, who stayed with the show until their early teenage years. The wordless dance-theatre piece The Record starred 45 ordinary people, of all ages, cast anew in every city in which the show opened. In The Fever, audience and performer were almost indistinguishable, seated arm-to-arm in chairs arranged in a large square on the stage before rising to build the show together.

In early 2020, Browde and Silverstone were already workshopping the show that would become Part Two: An Encounter, as they grappled with American anxieties about ideological division, exacerbated by a stressful election year. In it, two strangers sit at a table, seeing each other across a distance but not losing sight of that distance.

“We’re not trying to pretend there’s harmony between us,” Silverstone explained. “We actually want to frame the fact that we don’t see eye to eye, that we’re sharing this furniture and this room, and we are not together in any way, shape or form. We can pretend to be for an hour, but the truth is, we know we will always see things differently.”

When COVID-19 hit and human contact vanished, it was A Thousand Ways’s executive producer Thomas O. Kriegsmann who saw a path forward. “Tommy was the one who had a sober sense of how long this was going to last,” Silverstone said. “And he’s the one who helped us structure the idea of a triptych, of a project that could actually guide audiences from this moment of isolation to this moment of togetherness.”

Dramaturg Andrew Kircher and line producer Cynthia J. Tong soon rounded out the Thousand Ways team. “We spent all summer online with each other, and held on,” said Silverstone. With Kircher, he said, they’d stay up until 2 a.m. talking through scripts and thinking through the three-show arc. Tong handled the mechanics of getting each show up and running. “She makes the whole thing happen,” he said.

Kriegsmann started calling previous 600 Highwaymen presenters to gauge interest in joining forces; early co-commissioners included Stanford Live, NYU Abu Dhabi, and On the Boards in Seattle. “We were all in this moment of freefall when the lockdown happened—like, whoa, is our art form extinct?” Browde said. “And Tommy had this perspective into the institutions, that they were also like, What do we do? He saw that there’s a mutuality here. We all need each other.”

For On the Boards artistic director Rachel Cook (she/her), the shows were an easy yes. “This idea of longing for a connection, it seemed like the right moment to try something like this out,” said Cook.

Part One was built in part in response to missing the liveness of regular human encounters, and the Zoom theatre of early quarantine wasn’t helping. “We were feeling like, Gosh, I’m really not needed here as a viewer,” Browde said. Talking on the phone took on an unexpected potency. “It still somehow felt embodied, because it wasn’t asking me to play this game of pretend, where I’m looking into a camera and we’re pretending to see each other—because we’re not,” she said.

In hindsight, it seems obvious that telephone calls facilitated connection across a vast distance—that’s literally the point of phones—but Browde and Silverstone were still shocked at how far-flung their callers have been. “In this moment, we’re both completely bound to our place, but [place] is also very vaporous,” Silverstone said. “It threw us for a loop in an incredible way.”

The numbers are indeed incredible. For On the Boards’ February 2021 presentation of Part One: A Phone Call, Cook told me, 58 percent of participants were first-time ticket buyers (typically somewhere between five and 15 percent), and 73 percent were from 25 miles or more outside of Seattle. “We had people from Canada, Ireland, New Zealand, England, Hong Kong, Iceland, and Mexico,” Cook said. “I get a little bit utopic, like, This is how theatre is connecting us across the world.”

The show’s individual connections also create a sense of responsibility to another person. In thousands of calls to date, Silverstone can’t recall anyone ever calling it quits and hanging up.

For these historically hands-on artists, letting go has been a challenge. They keep close tabs on shows via box office reports and a feedback hotline they set up for participants to share their experiences. Otherwise, there’s no record that these experiences even happened.

Since its American premiere at On the Boards last September, Part One has since been presented by theatre companies from Arkansas to Abu Dhabi. But Part Two has opened piecemeal, for obvious safety and logistical reasons. I caught it during its March 4-14 run at Seattle’s On the Boards. A few weeks after my phone call, I sat across from a masked stranger in a pool of light on the company’s mainstage. Plexiglass and a stack of notecards with words and actions separated us. We read our cards and undertook simple collaborative tasks. Later, we became storytellers, spinning a tale about attending a party in winter and slipping on ice in too-fancy shoes.

My experience of A Thousand Ways so far has been the inverse of all too many theatrical experiences: While I was very literally told what to do, I never felt like I was told what to think. Sitting in a theatre again after so long, during Part Two, I thought about the ways we extend unspoken kindness, the way we follow rules or don’t, how we follow and lead. I cried, not because the show led me there but because it met me where I was. Being really looked at by someone else can be excruciating, and this has been a hard year.

According to Browde and Silverstone, building these shows on the fly in collaboration with so many theatres has been a beautiful, surprising reminder of what it’s like to like to just turn off the lights and make a show together. Or not quite together: Plans are for Part Three to premiere at the Singapore International Festival of the Arts in May (a U.S. premiere remains TBD), but without 600 Highwaymen present. “The process of making Part Three that has us written out of the experience is probably the greatest thing that could possibly be, even though we don’t know how the hell we’re gonna do it,” Silverstone said.

For this company, the art is all in the crafting of instructions; when these instructions are built, the rest is up to us.

“Our hope is that the project is fully created by the people doing it,” said Silverstone. “We’re always interested in taking risks in our shows, something where we’re like, Oh my God, I can’t believe we’re doing that,” he said. “This show feels to me like it’s taking that idea all the way, which is like, taking audience members, putting them into a theatre together—and then walking out the door.”

Gemma Wilson (she/her) is a contributing editor to American Theatre.