Picture a telephone booth, if you’re old enough to have seen one of those, or a shower stall with glass doors. Except this one is on wheels, and instead of running water or a landline inside, this one comes equipped with soundproofing, pull-down blackout shades, and a pair of headphones. It is a safe space meant to offset a chaotic environment, tucked in the back of a crowded theatre or in the corner at a rock concert. With a little ingenuity, it could be the future of sensory-friendly performance.

Live theatre is a mixed bag of sights and sounds. It can be loud, bright, and startling even for the most unflappable audience members. Neurodivergent theatregoers still want to be able to have fulfilling experiences. While programming labeled as sensory-friendly is often tailored to young audiences, or features a toned-down version of a production, the members of Spectrum Theatre Ensemble, a company of neurodiverse theatre artists based in Providence, R.I., believe that such efforts can cheapen the experience. After all, what is Hamilton without a gunshot? Instead of altering production elements, Spectrum advocates for theatres to provide warnings about content and even live special effects so that potentially affected audience members can be fully prepared.

The company is now in the early stages of developing their NICE (Neurodiverse Inclusive Certified Entertainment) program to establish standards of practice and implementation guidelines for the inclusion of neurodiverse audiences and theatremakers, somewhat akin to the LEED rating system for environmentally friendly institutions. STE is currently piloting the certification program in the Boston theatre community with American Repertory Theater.

“I think the NICE program is a very good way for STE to get involved with other theatres and to promote the idea of inclusive entertainment that doesn’t infantilize or, frankly, bastardize productions,” said resident playwright Dave Osmundsen. “A lot of neurodivergent-friendly performances on Broadway tend to be Disney shows or shows that appeal to a more general audience. But we find that there are neurodivergent audiences who want to see Sweeney Todd, who want to see Fun Home. They want to see riskier works, and they don’t want to see the ‘autism version’ of that production. They want to see the production as it was directed,” though with additional sensory supports put in place.

Osmundsen explained, “It’s really about giving neurodivergent audiences agency in their own experience of a production.”

While they do not yet currently exist, portable, sensory-friendly booths as described above are one of the measures suggested by NICE, along with such recommendations as live warnings in advance of particularly intense lighting and sound cues. Designed to create a safe bit of distance from the action, the booths would give people a place to take breaks without having to exit the theatre or retreat to the bathroom if things become overwhelming. The audience member could simply close the door, pull the shades, and block everything out, or adjust the volume on the in-booth headphones—and they wouldn’t necessarily have to miss what happens next.

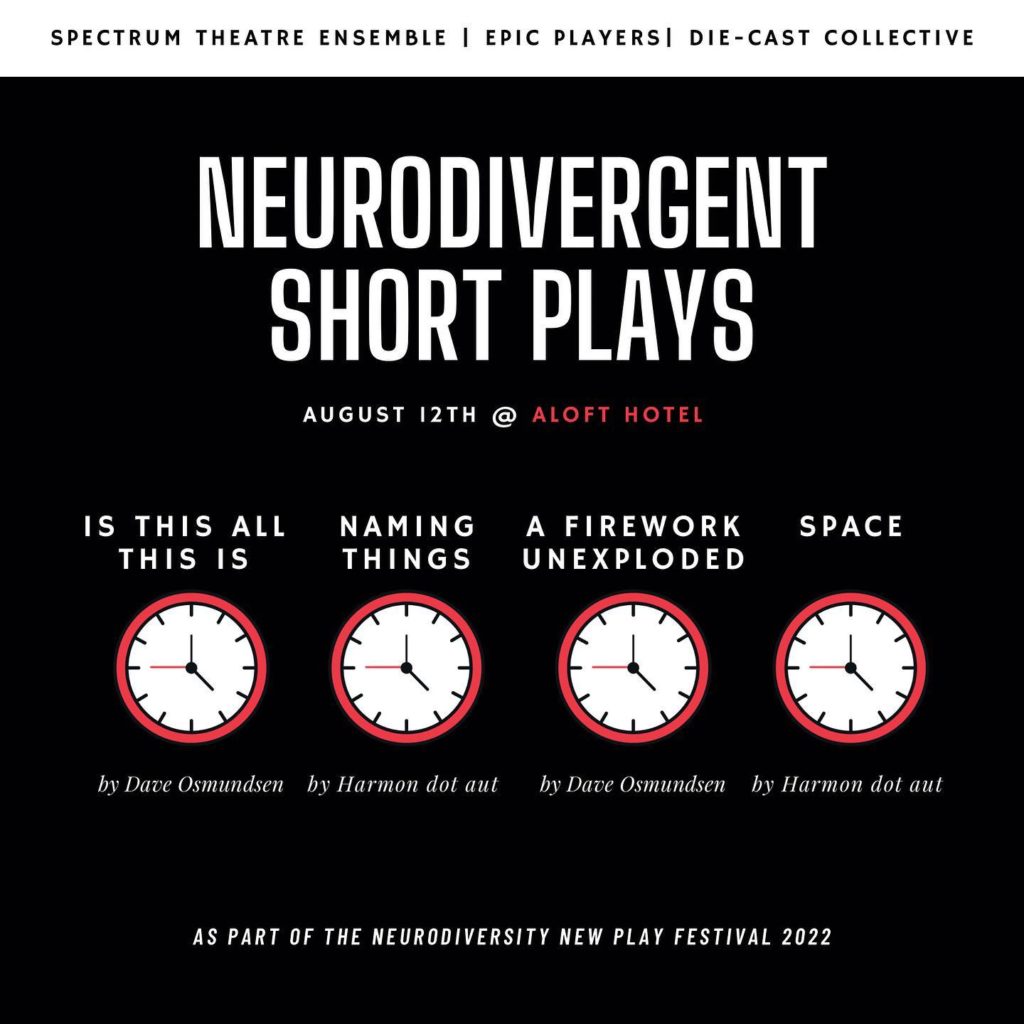

Better access for neurodiverse audiences is just one of Spectrum’s goals. The company is composed of many nuerodiverse artists, and puts a focus on fostering greater inclusion in the field. To that end the company develops productions created by neurodiverse playwrights and performers. In August I was on hand for their second annual Neurodiversity New Play Festival, which was presented in partnership by STE, EPIC Players, and the Die-Cast Collective and featured readings of four short play excerpts by Spectrum resident playwright Dave Osmundsen and director of new-work development Harmon dot aut, as well as an immersive installation Sense of Time: A Neurodiverse Devised Play.

Osmundsen’s two plays, Is This All This Is and A Firework Unexploded, explore their protagonists’ complicated relationships to the world around them. The former depicts an autistic character’s anxiety about navigating a job interview: Jamie is an autistic, non-binary lesbian who craves independence, but feels insecure about their place in the world. Support comes in the form of their aunt’s autistic boyfriend Tyson, who sees their potential and helps build their confidence. The play highlights the affirming process of creating opportunities for those who have been marginalized.

The latter play focuses on a couple failing to connect in their relationship. Ned loves fireworks, but Gina doesn’t understand his hyperfixation or how he can be so passionate about something so fleeting; she’s not sure whether she can even feel that deeply about anything. A Firework Unexploded offers an example of how neurodiversity can complicate romantic situations by delving into a discussion about the ways that chemicals react in time to create a singular spark.

“I gave my heart to him and he’s one of the best things that ever happened to me,” said longtime Spectrum ensemble member Daniel Perkins, who played Henry in STE’s premiere production of Light Switch as well as Ned in Firework, of his experience working with Osmundsen. “Dave writes these beautiful, complex characters, both on the spectrum and off, and he doesn’t make them either good or evil, just human beings.”

The characters he writes may be fictional, but their interactions are informed by real observations from Osmundsen’s life as a queer autistic playwright.

“The American theatre doesn’t know what to do with neurodivergent playwrights, because we’re not used to neurodivergent people telling their stories and centering themselves and their narratives,” Osmundsen said. “I feel like there’s this desire on a theoretical level for theatres to diversify, and we’ve gotten a lot better with BIPOC representation. But where does neurodiversity and disability fit into that? Disability is the only community where race, class, sexuality, and gender all intersect with each other.”

This is why, he continued, companies like Spectrum, EPIC, and Action Play “are really important. My hope is that neurodivergent representation does not stay siloed in those three companies and that it expands to regional theatres across the country.”

Harmon dot aut submitted a play to Spectrum in summer 2021 after spending many years away from the theatre. A mutual friend got in touch with them when STE artistic director Clay Martin put out a call for submissions to the Neurodivergent Playwright Initiative.

Harmon was diagnosed with autism and ADD as an adult—while already living with Tourette’s and a chronic illness—after having survived 20 years of medical and mental health treatment, misdiagnoses, and intermittent hospitalizations. The expensive diagnosis process took eight months, but it finally allowed them to mourn the years that they had lost and come to a place of self-acceptance.

“I think that truth is just, after all these years, the best thing in the world,” said Harmon, who is the sort of soulful, easygoing person with whom you could spend several hours sitting and talking in a coffee shop, nursing the same cup of black coffee until it’s well past cold.

Harmon’s two plays presented at the festival were Space and Naming Things. The first place arose from a desire to share the experience of being neurodivergent and poor, struggling with Medicaid red tape—a situation Harmon knows firsthand. Set in the waiting room of an underfunded mental health clinic in rural Oklahoma, Space introduces us to Margaret, a mad, nonbinary autistic poet who is waiting for an Access-A-Ride. As we wait with them, we gain insight into the way they see the world and come to glimpse fragments of their inner light through poetry and pop culture.

Naming Things is an autobiographical piece reflecting on Harmon’s experiences of abuse and electroshock therapy. It’s a play about striving to be joyful in the face of trauma, nurturing what Harmon calls a “fuck you spark,” and learning to sing your own song.

“The best experience that I had at the festival,” Harmon said, “was afterward, when a young autistic trans person came up to me and said, ‘I felt like you were telling my story.’ That’s everything, and we need so much more of that. For me the risk of being vulnerable, or just saying the truth, whether the truth is difficult for people or not, is worth it. There’s celebration in doing that. Because we haven’t seen ourselves in these spaces.”

Last Friday, STE hosted a holiday fundraiser and a selection of new-play readings at the Social Enterprise Greenhouse. The event featured readings from four of the six new plays selected for STE’s 2022-23 season, including Space, A Firework Unexploded, The Loudness of It All by Mashuq Mushtaq Deen, and Keeping Mum by resident dramaturg Craven Poole.

Sense of Time: A Neurodiverse Devised Play was developed over four days during the festival in collaboration with members of STE, EPIC Players, and Die-Cast Collective. Facilitated by Die-Cast co-founder Brenna Geffers, Sense of Time took its theme from conversations with Harmon dot aut, who has complex synesthesia, a perceptual condition triggered by the stimulation of connected sensory pathways, leading to linked sensory experiences, like seeing smells or feeling colors. For Harmon, this includes a visual and tactile perception of time in space.

“It’s like I can hold it. I can feel it, it is tactile,” Harmon explained. “It’s almost like the concepts of past, present, and future don’t really make too much sense to me, because clocks to me are all wrong. All clocks really are just timers. They are designed to make sure that we’re all on time to our appointments. Time to me is like little thin slices. I have to kind of physically pull them out and go, ‘Oh, that’s a memory.’ Almost like a record cabinet.”

The Die-Cast storytelling approach consists of a collective creation process, in which participants individually determine their relationships to the space and then investigate how their narratives intersect. The name Die-Cast refers to the process by which hot metal is poured into a mold; when the entire mold is filled, a new shape is made. In this way, the work of the Die-Cast Collective is shaped and inspired by the different spaces they occupy. This time around, the performance was influenced by artists’ perspectives from the three different companies.

Die-Cast Collective first met Spectrum Theatre Ensemble in 2017 when both groups were performing at the Provincetown Tennessee Williams Theater Festival. Meanwhile, EPIC Players had been working toward a similar mission in New York. The three companies knew that they were bound to collaborate at some point in the future.

Sense of Time premiered at Providence’s Social Enterprise Greenhouse, a hybrid office and performance space. Presented in 15-minute looping intervals, the immersive installation allowed audiences to get up close and personal with the actors, following them from room to room, through the doorways of different offices as they engaged in a series of vignettes, their own physical representations of the passage of time.

The synergy of their repetitive actions, borrowed song lyrics, and overlapping voiceovers expressing such thoughts as Can I be a positive change? When are you in all of this? and If I could turn back time… gave the impression of watching and rewinding a videotape. Voices and movements melded together into one indistinguishable moment.

The installation also featured a collection of “memory jars” containing seashells and Polaroid pictures. The program began and ended as the actors came together in the center of the floor in celebration, shouting, “Happy New Year!”

The program was designed in such a way that audiences could step away and rejoin the narrative at any time, safe in the assurance that it would all repeat again in 15 minutes. I was tempted to try and follow each performer’s route through the exhibit, determined to understand how all of the pieces fit together. In this dream sequence of orchestrated cacophony, behaviors like stimming, ticks, and echolalia felt completely natural. Involuntary movements and sounds became as much part of the shared space as any other kind of expression.

“It’s rare that I am in a space where I feel like I don’t have to camouflage,” said Harmon. “When we were devising work, there were moments where I wasn’t even thinking about it, which is so rare. I realized I was stimming all over the place. It’s just me, you know, and it’s the frame.”

Geffers sees her role as a facilitator in the devising process as a kind of quiltmaker. “My job is to weave the pieces together to see how they overlap, and what parts are in conversation with each other, rather than forcing the conversation. There’s a lot of watching, observing, and weaving.”

Another original, Spectrum-infused element of the performance was the creation of a neutral, sensory-friendly space within the installation. The actors and observers could move into the quiet room at any time if the performance became overwhelming. While Die-Cast usually provides a walk-up bar or a designated area with tables for audience members to congregate during their immersive projects, this was the first time they set aside space for the artists to decompress. Geffers said that the collective is interested in adopting this practice for future performances.

“I’m a very anxious person in real life, and I’m actually pretty shy,” Geffers admitted. You would never know this from watching her lead rehearsals, in which she is calm and approachable. “When we’re working, I just want to see what we’re making happen so much—that’s all that matters. Because we’re working so quickly, I want them to know that they can trust me, and that I’ve got them and that they can’t do anything wrong. I think that’s how people should feel when they’re building. They should feel that somebody believes in them, because I do, and that’s what makes people brave.”

This festival collaboration was considered by all parties to have been a success, and there is certainly room for more like it between these three companies in the future.

“Everyone from our team at EPIC definitely wants to do this festival again,” said EPIC associate artistic director Travis Burbee.“I know we’re hoping for that, and I’d love to do more with STE. I was a big fan of theirs before going to Providence, but being there and meeting so many members of STE and the team only made that desire to work with them stronger.”

Geffers was also enthusiastic about the experience. “This is the beginning of a conversation that we’re hoping to develop and continue,” she said. “It’s a little bit like a first date. We got a sense of how we work, what parts of our work jibe well together and what parts don’t. I think we learned a lot, and mostly, we found a sense of trust and joy and pleasure in working with each other, which, if you have that, then I think then you can build almost anything from there.”

Building community seems to be Clay Martin’s specialty.

“One of the assets that Clay really brings to the table is his ability to get these great people in a room together,” said founding STE Member Jason Shipman. He said that this collaborative spirit goes back to Spectrum’s early days when they were “just a bunch of knuckleheads putting on a show in Barnaby Castle, listening to Elton John’s Captain Fantastic and the Brown Dirt Cowboy album on repeat.”

Shipman met Martin while studying theatre in undergrad at a branch of the University of South Carolina in Aiken. Together they spent summers working at the Lost Colony and witnessed a nonverbal autistic woman find her voice through song.

Spectrum Theatre Ensemble was born out of a desire to make theatre that functioned as social engagement, while creating space in the industry for neurodivergent voices. Martin was just starting graduate school for theatre pedagogy and practice at Texas Tech University when he was told, as someone with autism and ADD, that “maybe graduate school wasn’t the right place for me, because I couldn’t advocate for my disability without accommodations.” But rather than accepting ableist judgment as defeat, Martin walked across the street to the Burkhart Center for Autism Education and Research and started his own project.

With the help of a Leadership U One-on-One mentorship grant from TCG, Martin and his creative partner PJ Miller were able to establish Spectrum under the umbrella of Trinity Repertory Company. Once Spectrum had found its footing, the ensemble went on to become its own nonprofit.

In 2019, following a series of mass shootings, President Donald Trump suggested reopening the asylums. One of Spectrum’s older members had survived being institutionalized. This man, grizzled and in his 40s, as Clay described him, reportedly walked into a meeting and said, “We need to do One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest right now, because we need to remind people why we closed those places.”

This led to a groundbreaking neurodiverse production of Dale Wasserman’s classic play about patients in a psychiatric hospital. Teddy Lytle—the spitting image of Jim Carrey if he were much sunnier and went platinum blonde—played Randle (Mac) McMurphy, and described the experience as “life-changing.” He credited his work with Spectrum as being integral to his sobriety and expressed gratitude for Clay “always taking a chance on me.”

This experience of reclaiming a piece of disability history eventually led to STE’s new-play development initiative, as Martin realized how few plays were written by neurodivergent playwrights.

The desire to cultivate a sense of neurodivergent belonging further fuels NICE, Spectrum’s Neurodiverse Inclusive Certified Entertainment program, which is all about making people with sensory needs feel welcome in the theatre. STE executive assistant Korbin Johnson notes that NICE is not a one-size-fits-all model, and that theatres should be encouraged to innovate based on the needs of their audiences.

“There are so many different ways that we can make things accessible,” Johnson said. “It’s just a matter of bringing in the right people, having the will power, finding ways to reach audiences, and making sure that it’s implemented thoughtfully.”

Johnson is currently a junior studying theatre and arts management at Roger Williams University. As an autistic person, they were inspired to get involved with sensory-friendly entertainment after noticing how overstimulating big concerts could be for folks on the spectrum and those with PTSD. Johnson got in touch with Martin, who offered them an internship. The goal of the NICE program is to teach institutions how to best support neurodiverse theatregoers and theatremakers.

“NICE is a full training program, where you get certified in various aspects of sensory-inclusive practices,” Johnson said, “not just for audiences, but also for neurodiverse actors, performers, and anyone on the creative team as well, so that anyone can feel supported.”

Part of Johnson’s work as a sensory-friendly consultant for NICE involves viewing productions at partner theatres and marking down moments in their scripts with a one to five rating for the intensity of sound or lighting effects. The theatres then have the option to subtly alter the production design to reduce the effect, or to provide a warning. At Spectrum’s productions, for example, they use a non-disruptive warning light as a signal to audience members before a loud noise or flash. One day similar warnings could be given via a vibrating handheld device or a light on an armrest for patrons who request them.

Though the NICE program still has a long way to go as far as widespread implementation, the hope is that regional theatres across the country will begin to engage in conversations with neurodiverse audiences and artists about their access needs. It comes down to a question about ownership: Who is theatre made for, after all, if not everyone?

Alexandra Pierson (she/her) is associate editor of American Theatre. apierson@tcg.org