The visionary theatre and opera director Robert Wilson (Einstein on the Beach, The Black Rider, Hamletmachine) died on July 31. He was 83.

In the restless, electrically charged atmosphere of New York City during the 1970s, I found myself irresistibly drawn to the enigmatic figure of Robert Wilson. I was a young director looking for inspiration and Wilson—already a legend in avant-garde theatre—exerted a magnetic attraction. If I saw him on the street, I would abandon whatever I was doing to surreptitiously follow him, careful to remain unnoticed. To me, Wilson was a complete mystery. His theatre, which blended movement, silence, and image into haunting and new expressions, defied all the conventions I had been taught. I wondered: How did he conjure such extraordinary worlds onstage? What did he notice that others missed? Was he able to see and interpret things that were otherwise invisible or insignificant? Following him on the street became my own private ritual, a way to study not only his art but the man himself. I was fascinated by the way that he dressed, how he moved, and how he interacted with the world, and I was curious to learn about what he paid attention to. Perhaps I wanted to imitate him. Or perhaps, in following him, I was, at the time, searching for my own path.

Even before I experienced Robert Wilson’s work firsthand, his reputation had already reached me through the breathless accounts of fellow theatremakers. Wilson, working with his legendary collective, the Byrd Hoffman School of Byrds, was said to push the boundaries of performance far beyond conventional limits. I heard stories about his groundbreaking productions: The King of Spain (1969); the seven-hour epic The Life and Times of Sigmund Freud (1969); the “silent opera” Deafman Glance (1970), which also lasted seven hours; and the monumental KA MOUNTAIN AND GUARDenia TERRACE (1972), staged at the Shiraz Festival in Iran, which ran 24 hours a day for seven days and sprawled across seven hills, featuring hundreds of participants. There was also The Life and Times of Joseph Stalin (1973), which spanned over 12 hours.

Hearing about these extraordinary feats, I was left wondering how such miracles of theatre could even take place. What kind of mind could conceive of such ambitious works, and what kind of community could possibly bring them to life? The scale, vision, and collaborative spirit behind Wilson’s productions seemed almost unfathomable, challenging my understanding of what theatre could achieve.

The first Robert Wilson production that I experienced in person was The $ Value of Man at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, a performance that immediately signaled that I was entering uncharted theatrical territory. Not long after, I saw A Letter from Queen Victoria on Broadway, followed by smaller, more intimate works, like Emily Likes the TV and I Was Sitting on My Patio This Guy Appeared I Thought I Was Hallucinating. Eventually I witnessed the monumental Einstein on the Beach, a production that left an indelible mark on my understanding of what theatre and opera were capable of. Each of these works felt as though Wilson had invited the audience into a dreamscape—a world governed by its own internal logic of time, movement, and image. The boundaries of narrative and realism dissolved, replaced by a hypnotic sequence of visual and auditory tableaux that seemed to reinvent theatrical vocabulary before my eyes.

My early encounters with Robert Wilson’s work opened my eyes to new possibilities in live performance. Though I do not consider myself an auteur, watching his productions taught me how meticulous stagecraft can create its own internal logic, departing from conventional narratives. What impressed me the most was the precision of his movement and design. Every gesture was intentional, and his minimalist, abstract sets transformed space into a means of expression, conveying meaning through suggestion rather than direct depiction. In Wilson’s hands, space became a language, communicating through abstraction and subtle implication rather than simply reproducing everyday reality. His productions moved with a distinctive rhythm that suspended the ordinary flow of time and heightened my awareness of each moment.

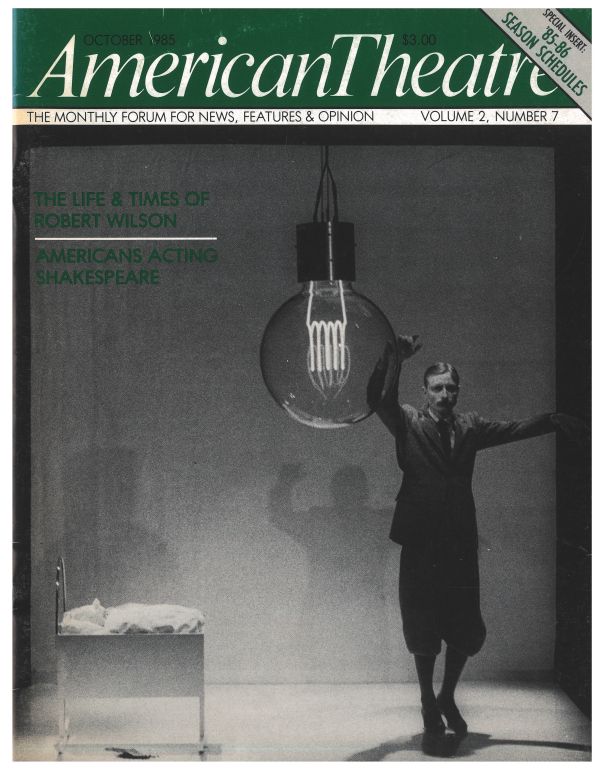

Through his productions, I also discovered the transformative power of lighting. For Wilson, lighting was never simply a means of illumination; it became a sculptural and emotional force, shaping the very architecture of the stage. He used light to carve out space, create depth, and shift the atmosphere with subtle gradations or dramatic changes. Shadows, color, intensity, and movement of light all serve as expressive tools. In Wilson’s hands, light became a storyteller in its own right—as evocative as a gesture or a line of dialogue. His work revealed to me how profoundly lighting can define not only the mood and visual world of a performance, but also its narrative and underlying meanings. In Europe, Wilson’s revolutionary use of lighting fundamentally redefined what lighting could accomplish onstage, inspiring a generation of theatremakers there to recognize lighting design as an essential and creative dimension of live performance.

Above all, for me, Wilson exemplified how essential a sense of control is to the creative process. Observing his work, I realized that true artistry is not just about flashes of inspiration—it is about deliberately shaping and harmonizing every element involved in a production. Wilson personally oversaw minute details in his shows, from the way an actor moved across the stage to the precise angle at which a single beam of light illuminated a character’s hand. This painstaking attention to detail ensured that his productions formed a cohesive, visually striking theatrical world.

Especially in his early career, the careful control that Wilson exercised was balanced and enlivened by the creative energy of the Byrd Hoffman collective and influential collaborators like Deafman’s Raymond Andrews and the autistic poet Christopher Knowles. Their input brought spontaneity and unexpected discoveries, fueling the innovative spirit of Wilson’s groundbreaking early works. Over time, his unwavering dedication to precision and his desire to shape every aspect of his productions resulted in works of remarkable cohesion and visual beauty. While his meticulous approach may have changed the character of his later creations, it also ensured that each piece bore the unmistakable imprint of his singular vison—testament to an artist wholly devoted to his craft.

In Europe, Robert Wilson was not only a renowned director; he became a household name, affectionately referred to by many as just “Bob.” His reputation still sparks lively conversation wherever theatre is discussed, and his influence is widely felt. The renowned French writer Louis Aragon was the first to publicly recognize Wilson’s visionary talent. After attending Deafman Glance in Nancy, Aragon wrote a letter to his late friend André Breton, which was published in Les Lettres Francaises in 1971. In this letter, Aragon proclaimed that his work embodied “what we dreamed (surrealism) might become after us, beyond us.” This powerful endorsement effectively positioned Wilson as a creative heir to the Surrealist movement and played a crucial role in establishing his reputation across Europe and beyond. An excerpt from Aragon’s letter:

Dear André, I’ve seen the most beautiful thing in my life…You would have loved it as I did, to the point of madness (because it has made me mad.)…I never saw anything more beautiful in the world since I was born. Never, never has any play come anywhere near this one, because it is at once life awake and the life of closed eyes, the confusion between everyday life and the life of each night, reality mingles with dream, all that’s inexplicable in the life of a deaf man.

Anne Bogart is an American theatre and opera director who served for decades as one of the artistic directors of SITI Company.

Support American Theatre: a just and thriving theatre ecology begins with information for all. Please join us in this mission by joining TCG, which entitles you to copies of our quarterly print magazine and helps support a long legacy of quality nonprofit arts journalism.