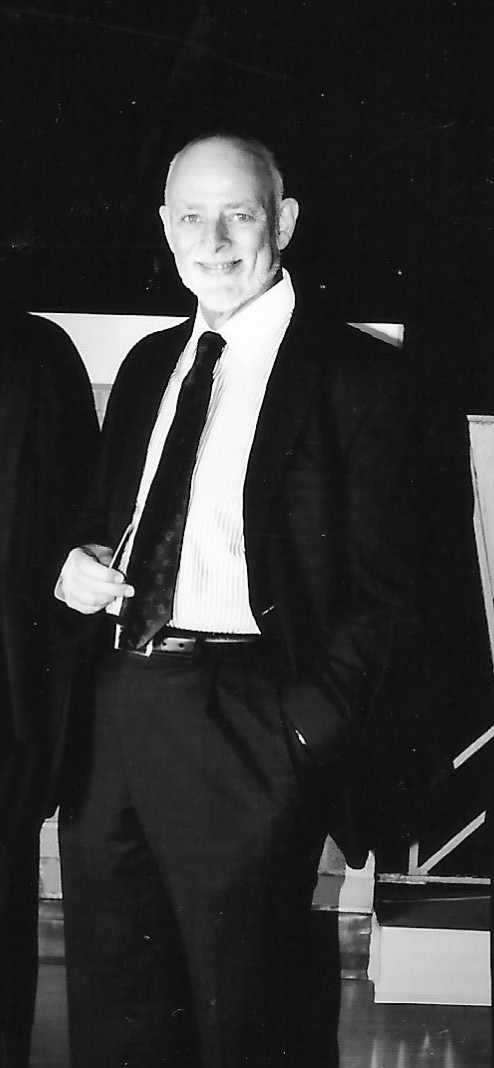

Robert A. Freedman died on Sept. 22 at the age of 89. Perhaps it’s appropriate that this memoriam is being written on a cold and wind-swept rainy night, a fitting and dramatic setting for someone whose entire life was dedicated to the theatre.

Bob was born in New York City in 1936 and graduated from Swarthmore College in 1958, and later from the University of Pennsylvania School of Law in 1961. He came from an illustrious lineage: His father was a pioneering literary agent who founded the Harold Freedman Dramatic Agency in 1928, an agency that Bob took over when he turned 30 and continued to develop into the Robert A. Freedman Dramatic Agency, which he shepherded for six decades. Together, father and son represented many of the playwrights we now recognize as pivotal in the transformation and elevation of American theatre into an art form that embodies and reflects the moral complexities of the human condition and the confounding incongruities of our culture. Their roster included Lawrence and Lee, Noël Coward, Robert Sherwood, Maxwell Anderson, Thornton Wilder, Clifford Odets, Elmer Rice, J.B. Priestley, John Osborne, Paul Osborn, Sidney Howard, Terence Rattigan, Philip Barry, Mary Chase, Jean Kerr, S.N. Behrman, and many others.

Bob was of another time, a time rapidly receding into memory, as well as a purveyor of an ethos that is more and more neglected, forgotten, and circumvented for the sake of material gain and expediency. He was a giant in his field with an outsized legacy, and those few who remain and who knew him have provided their personal testimonials for this article in reflections that cite his unflinching integrity and kindness, and his unwavering dedication to playwrights for whom he was not only an ardent advocate but a loyal confidant.

He was a storyteller whose encyclopedic knowledge of our industry was legend, making it all the more vexing that, despite everyone who knew him constantly begging and cajoling him to write his stories down (myself included), he would always demur. Perhaps their loss is on us, for we all knew that we should always have a tape recorder on hand whenever we would meet him, knowing that at some point he would invariably launch into a long, long story that would never be told or heard again. So, to make partial if futile amends, I have reached out to those who knew him to share some of their memories for this article, and to provide personal testimonials to conjure the expansive spirit and moral essence of this self-effacing man who has played such a pivotal role in our field.

Samara Harris, literary agent, Bob’s daughter:

Bob was my stepfather, my champion, and my mentor, and I miss him so much. He helped shape who I am and the person I continue striving to become. He was a person of the utmost integrity, with a strong moral compass, and that guided both how he worked and how he lived. He loved the theatre, and he loved writers. His clients were never just clients; they were his friends and his family, and he cared about them and their work deeply. He passed that on to me, and I am proud to carry that same love and respect for the writers and directors I’ve had the honor of working with.

Bob introduced me to the theatre world and to so many profound artists. Many of the connections, colleagues, and friends I have today are because of him. And he didn’t just make introductions for me, his stepdaughter; he did it for countless others throughout his life. That was Bob. He had a gift for connecting people and making their lives richer just by bringing them together. He enriched my life, and the lives of so many others.

And Bob had so many wonderful stories—oh, how he loved sharing them. I would walk into his office with a quick question about a contract and end up there for an hour and a half, hearing the most wonderful stories, and learning not just about Bob but about the theatre and its evolution. He gave his time freely to others, sharing his knowledge, meeting with playwrights, writing articles for publications, teaching, and mentoring. When he came to speak in my theatre history class at Ithaca College, I was filled with pride and gratitude that he could share his experience and insight with all of us.

One of the most comforting and valuable things Bob taught me was that people make mistakes, and I certainly did and still do. All people do. He always included himself in that truth. He reminded me that we all stumble, and that’s okay, because that’s how we learn. Our mistakes don’t define us; what matters is what we take from them and how we move forward. And Bob was always clear that it is better to come from a place of integrity, to hold onto your values, than to sacrifice them for what you think might be success. In the end, what matters is how you treat people and being able to put your head on the pillow at night knowing you did your best and did not compromise your values.

Bob lived his life with such grace, kindness, and integrity. Let us all carry some of Bob within us and live our lives a little more like him—in the way we care, the way we work, and the way we treat each other.

As Thornton Wilder wrote in Our Town: “We all know that something is eternal. And it ain’t houses, and it ain’t names, but something that has to do with human beings.”

Robert Vaughan, senior vice president, Theatrical Rights Worldwide, plays:

I came into the business in the 1980s and was lucky enough to work with many of the last of the great agents, such as Audrey Wood, Margaret Ramsay, and others who gave the world some of the biggest legends ever (Tennessee Williams, Marlon Brando, David Hare, Joe Orton), and who trained the next generation. Harold Freedman gave us legends, too, such as Thornton Wilder, Jerome Lawrence & Robert E. Lee, and many others, and he also gave us his son, Bob, who followed in his father’s footsteps and took over the family business.

Bob was truly one of the greats, and sadly, probably one of the last. I was an assistant at Samuel French the first time we spoke, but that didn’t matter to him as it did to some, and by the time I became director of professional rights at Dramatists Play Service, he treated me as a peer, not some whippersnapper. The key for him was respect. Bob genuinely loved what he did and the writers that he represented. If you didn’t love what you did, he could smell it a mile away, but if you loved your writers, you were in, and he respected you, and if you knew your history, all the better.

I immersed myself in theatre after finding it in high school, and devoured every book in every library, so working with the people who represented my gods was blinding. I was able to tell Bob that one of the first plays I read was by his client, Robert E. Sherwood, and I could name the theatre, the cast, and the director of the original Broadway production of The Petrified Forest, which was so exciting for me. It was just as exciting for Bob as was the fact that Sherwood’s Idiot’s Delight is one of my all-time favorite plays. Bob loved telling stories, and his stories were amazing.

Once I had to call him about Harvey because a theatre had some very odd questions and requests. Bob knew more about that (giant imaginary rabbit) “Pooka” than I could have ever dreamed, and he spoke to the meaning of Mary Chase’s play as if he’d written his dissertation on it. We talked about everything. I cherish that, and I begged him to write a book, which I hope he did, or at least got started.

Marta Praeger, agent at Robert Freedman Dramatic Agency, Inc.:

Bob was a fierce advocate for authors’ rights. He was closely involved with the Dramatists Guild from its beginnings and was one of the lawyers who argued before the Supreme Court to make the Guild a union. Though this did not happen, he continued to help shape the direction of the agreements for authors’ protection, and many of the authors he represented were original members of the Guild.

Bob’s father, Harold Freedman, was responsible for starting Dramatists Play Service to allow playwrights to have their works performed throughout the country. He was always working intimately on his clients’ behalf, and whenever anyone tried to locate an obscure play or author, they would call our office since they knew of his vast knowledge of theatre history. He had integrity and was greatly respected, and was involved in the beginnings of the Association of Authors’ Representatives, advocating for the ethical behavior of agents.

Joel Stone, literary manager, New Jersey Repertory Company:

In remembering Bob, I fondly recall his stories about a Broadway long gone, a New York City of writers and celebrities sitting around tables at the Algonquin and at Sardi’s, a time when Manhattan seemed like the artistic center of the universe. I remember his tales of spiritual quests, and of journeys outward and inward. Several times, I told him, “What a fantastic life!” and asked, “Why don’t you write these stories down?” It was a question that was usually met with a wry smile and a shrug—and now those tales are gone, taken by Bob to a place beyond our comprehension, a place that filled him with curiosity and awe. He was one of a kind.

Richard Strand, playwright (Ben Butler):

Bob was my agent for 37 years, the only agent I have ever had, and over those years, he and I met up often, all across the country, whenever he would show up for the opening nights of my plays. It was helpful to me that he always showed up in support of my work, and I enjoyed the insights he shared with me.

The fondest memory I have of him is of a time when we did not meet up. In 2005, Bob and I planned to meet in Long Branch to see one of my plays on its opening night at the New Jersey Repertory Company. I had purchased my plane ticket and had arranged for a place to stay, and my ticket was being held at the box office. But shortly before I was to fly, my wife was diagnosed with breast cancer, and the prognosis was uncertain.

I emailed Bob to tell him that I wouldn’t be meeting him, and I told him why. Very soon after I sent that email, I got a phone call from Bob. He wasn’t known for brevity, and I wasn’t sure I wanted to have a long talk with him at that particular time, and I considered letting the call go to voicemail. When I answered the phone, I learned that Bob wasn’t calling to talk to me; he wanted to speak with my wife. And I don’t know how long they spoke or what they spoke about, but I know that I heard my wife laughing, and it had been quite a while since I heard my wife laugh. When she hung up, she was in a decidedly more optimistic mood.

Now, it’s important for me to clarify that my wife’s cancer treatments went well and that she is a 20-year survivor. But she still appreciates that my agent, whom she did not know well, thought it was important to talk to her at a difficult time in her life. She remembers that phone call fondly, and so do I.

Gabor Barabas, executive director, New Jersey Repertory Company:

I have my own recollections of Robert from the perspective of a producer, and what always struck me whenever I dealt with him as a literary agent was that he was somewhat different from all the others, perhaps what one would think of as “old school” (whatever that means). Negotiations with Bob never began with rights, compensation, or royalties, but with him seeking to understand who I was and what our theatre stood for.

Of course, he was forever meticulous in his formal representations of his client’s interests, especially since he wrote and designed some of the contractual standards and framework that we use in our industry today. But what he was seeking was something else: He was searching for signs of a kind of integrity and self-reflection, and for where we saw ourselves in the pantheon of theatre, and it became quickly apparent that trust was most critical and that we needed to convince him before he would ever turn over his client’s precious work to us that we saw the play’s worth not in material terms but that we recognized, as he did, the artistic achievement itself, and the dogged and oftentimes lonely creative impulse that created and ignited the work in the first place.

We would talk about a play’s spiritual underpinnings, its cosmic implications, and its psychological authenticity. He needed to be assured that we would treat his playwright’s work with respect and care; otherwise, our engagement went no further. But if it did go further, then there was always an obligatory “handshake,” a necessary indicator of our mutual faith and trust in one another. This is how Bob advocated for his playwrights, and whatever formalities followed were but an afterthought.

One of the last times I saw him, Bob had taken a train to our theatre, and, yes, it was a dark and cold, and rainy night. I was struck by how fragile and old he looked. But not in spirit, for in that he was in top form. His eyes glowed with excitement when, at some point, he launched into a long, long story. I kick myself for not having had a tape recorder. But then perhaps this was the point all along. He was one of a kind.

Bob is survived by his wife, Marisa Harris; his daughter, Rachel Freedman; his stepdaughters, Jenna Cohen (James McGee) and Samara Harris (Chris Anderson); and his grandchildren, Abigail, Charlotte, Annelise, Hugh, and Elsa. He is also remembered by his extended family at the Robert A. Freedman Dramatic Agency, Brandt & Hochman Literary Agency, and by the countless writers, producers, and theatre professionals whose lives he touched.

The work of the agency will continue with the same integrity, diligence, and commitment to professionalism that Bob would have wanted. The proprietors, plays, and writers will continue to receive the attention and care they deserve. Bob would have wanted nothing less.”

A memorial will be scheduled for January or February.

Support American Theatre: a just and thriving theatre ecology begins with information for all. Please join us in this mission by joining TCG, which entitles you to copies of our quarterly print magazine and helps support a long legacy of quality nonprofit arts journalism.