THE BLISS OF CHAOS

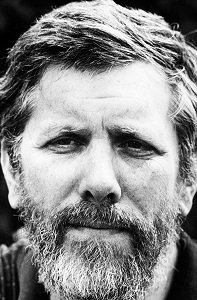

By Christopher Barreca

My relationship to the Clambake started in the early ’80s, when I was Ming Cho Lee’s assistant. As a professional designer, I have been a reviewer of works, and, for the past 17 years, I have sent our CalArts students to have their works reviewed.

It is hard to imagine that the Clambake will end. It is now a part of the fabric of my students’ education—the culmination of a chapter in their lives. Ming’s intentions are clear: to have a critical forum for a “national graduating class,” a sense of a beginning, a sense of belonging to a professional community.

Now there are others who are trying to emulate the Clambake, because they have come to see the value in it. The Clambake, I believe, has succeeded by example. Each year there is Ming, ensconced in front of a student engaged in an intense discussion, then another, and another. Very focused on making sure he gets to every student, Ming sees value in collective critique that is only about the work.

Students are always surprised by how the Clambake impacts them. They come to see themselves not as an isolated designer, or one in a school of designers, but as part of a design community. They experience what is unique about themselves and the uniqueness of others around them. They see what they know and what they don’t know. They are surprised by how quickly they develop relationships. They are surprised by the questions they are asked. They are surprised by how much they care about their own work. They are surprised that they quickly mature during the event. They are surprised at how they find advocates for their thinking and skeptics, and by how interesting it is to talk to both.

The Clambake is also notorious for being a reunion for all of us designers and teachers. Often Betsy has to prod us to stop talking to each other and focus on the students. But she does it with a nod and a wink—she knows that we enjoy seeing each other again. We catch up, laugh about some travail or other, and have an occasional design meeting right on the spot. To an outsider, the Clambake is chaos; to an insider, blissful chaos.

Christopher Barreca has been teaching design since 1986 and is currently the head of scenic design at CalArts in Los Angeles. His Broadway credits include the musicals “Marie Christine” and “Chronicle of a Death Foretold” for Lincoln Center Theater, and he has designed more than 100 productions of classics at major theatres throughout the U.S.

… A REAL NICE CLAMBAKE!

By John Conklin

Clambake…. Lobsters, a beach bonfire roaring beneath a starry sky, roasted corn on the cob dripping with butter…. No, no, wait a minute…. A gathering, a convention, a conclave, a convocation, an assembly, a troupe of strolling players, a kaffeeklatsch, a town meeting, an overturned ant colony, an art exhibit, a college reunion, a homecoming festival, a classroom, a free lunch (but, ah, consider and credit the generosity involved here!), an anthropological study area, a ritual, a rite of spring (in which elders welcome sometimes nervous initiates into the sacred arcana of the tribe—no sacrifices allowed), a bar exam, a trade show (Ming often played down this aspect, but what is of more value to a young designer than a job?), a family get-together, a continuing and joyfully practical demonstration of the ideals and spirit of Ming and Betsy, a fiery crucible of young and old, of tradition and innovation, of renewal and invigoration, of idealism and practicality—the past, present and future mixed inextricably together and blazing up like a beach bonfire beneath a starry sky.

John Conklin is a theatre designer and teaches in the Department of Design for Stage and Film at New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts.

DREAMING DESIGN’S FUTURE

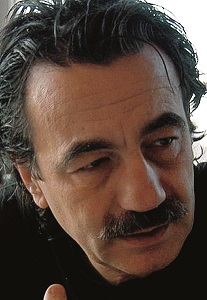

By George Tsypin

The theatre design department of New York University once occupied a tiny basement space on the Lower East Side. When I arrived for an admission interview with department head Lloyd Burlingame, I brought in paintings that could not fit in his office. I had to leave them outside. I had come from Russia about a year before and spoke very little English, but I had a big scarf and big paintings: Lloyd took a chance—I was admitted.

This was my second university education: I had graduated from an architectural school in Moscow a few years before that. The contrast could not be more striking. Moscow education was broad and extremely creative; we were taught to dream and conceptualize. American education was practical, technical, disciplined and demanding, completely oriented towards the job market.

I was lucky to go through both schools. Toward the end of the three years of the NYU graduate program, things started to pick up momentum. I was working on exciting opera projects for John Conklin, the school moved to a much bigger space on Broadway, and finally I had a chance to show my work at Ming Cho Lee’s portfolio review at the Juilliard School.

That was a life-changing experience. All of sudden, I had a chance to show my models to hundreds, maybe thousands, of people. These people knew thousands more people. It opened the world for me.

Ming Cho Lee, just as Lloyd Burlingame before him, played a crucial role in my life. Not only did Ming create the Clambake, he also helped me find my first job, the possibility of which, I thought, would be totally out of the question. All the directors I met then or in the next few years either had seen my work at Ming’s portfolio review or had heard about me from people who’d seen my work there.

I hear that next year will be the last one for Clambake. It is a big loss for theatre design in America. American theatre design needs many more events like the Clambake—not fewer. Young designers and students desperately need this kind of exposure and artistic exchange. The Clambake creates a perfect and rewarding closure after several years of intense and demanding courses in theatre design. Students mostly learn from each other, and the Clambake provides an ultimate opportunity for that creative interaction.

I dream of the day when the profile of the theatre-design profession would be increased, and people would actually know what theatre designers do. I dream of the day when it would become glamorous to be a theatre designer, and the best artistic talent would get involved in designing for theatre, opera and other live spectacles. I dream of the time when, at the end of the season, not only students and young people can show their work, but experienced designers can exhibit their latest achievements and share it with other theatre professionals. I dream of a time when these theatre designers would desperately be preparing for these exhibitions (just as the students do) and be filled with the same sense of anticipation and terror of being judged by their peers.

I imagine ordinary people actually coming to these events as they come to the latest museum openings. I imagine these future Clambakes discussed at dinner tables. That would make creative juices flow and start a whole new era of theatrical experimentation.

George Tsypin is an architect, sculptor and stage designer. His book “George Tsypin Opera Factory: Building in the Black Void” was published by Princeton Architectural Press and received the Golden Pen Award.

A PLACE TO CONNECT THE DOTS

By Dawn Chiang

The main focus of Ming’s Clambake is a portfolio review of the more than 60 graduating MFA students who specialize in scenery, costume or lighting design. But the many secondary benefits of this gathering include seeing what kind of training each of the graduate programs is providing. Examples: What schools emphasize a training in drawing and painting as an underlying background for design work? Who focuses on developing and executing strong conceptual designs, grounded in text analysis? Which programs are more tailored to the unique talents each student brings to their program each year?

Over the years, you can also see trends, such as how fluency in CAD programs has finally assimilated into training programs, or how some individual students have mastered a variety of rendering, 3-D visualization and animation programs that far exceed the scope of their training programs.

A great, unspoken gift of the Clambake is the strong sense of community fostered by the roster of theatre professionals who participate as respondents and teachers. Many return year after year, along with new or different individuals who join the Clambake each year. At the center of this event is Ming Cho Lee, renowned and revered for his insight, clarity and candidness in providing feedback as part of his training of design students. By inviting the respondents to the Clambake, Ming is asking all of us to also offer this same caliber of insight and dialogue in our one-on-one exchanges with the graduating students. Betsy Lee and her team form the event’s organizational core—without Betsy to make it happen, there would be no Clambake.

For many students, this is one of the first times that they have had the opportunity to see the work of fellow design students from around the country. For others, it is a first opportunity to receive feedback from a larger community that includes many award-winning and Tony–nominated respondents (the Clambake always happens a few weeks before the Tony awards).

On occasion, my conversations with students have served to underscore what they have learned. Many times, there is a shock of surprise to hear the same feedback from someone who has just met them that they have heard from a teacher they have seen weekly for the last few years.

Other times, there is an opportunity to connect the dots in a different way—to tease out and reinforce budding talents or instincts that have not yet fully emerged, but offer strong possibilities in the designer’s work.

I remember a student who had a great love of creating/sculpting three-dimensional creatures and characters, ever since he was a boy. Since this did not fall into the traditional category of set or costume design, he had put this passion of his to the side during his undergraduate and graduate school years. All the same, one of his maquettes cropped up as an item he displayed on his table at the Clambake.

The diminutive figure he had crafted clearly showed a strong, well-developed sense of character and a completely unfettered, creative vein in this individual. As we talked about his deep connection to creating this figure, I asked if he might be able use the same qualities of imagination, intuition, energy and joy of creation in the maquette when approaching his work as a theatrical designer.

There was a solid “Aha!” moment as he realized that his boyhood love of creating was actually profoundly connected to his adult impulse to be a designer—that all of that childlike curiosity, intensity and desire to express were exactly the impulses to which he could connect and open as a theatrical designer. It was there inherently within him, and he could now explore using those core instincts to guide his work.

That deep sense of community, connection, discovery and joy are what I so cherish in Ming’s Clambake, and will so miss when we meet for the last time in May ’09.

Dawn Chiang is a freelance lighting designer and a member of the board of directors of Theatre Communications Group.

A DIFFERENT WAY OF LEARNING

By Nic Ularu

For 33 years, several good generations of theatre designers and directors were inspired by this unique new-talent showcase, created by Ming and Betsy Lee. I have had the privilege to be a part of it as a reviewer—and to expose University of South Carolina students to the critique of some of the best contemporary theatre professionals and educators. It is hard to describe the joy, excitement and the sense of responsibility of my MFA students who have been participants at the Clambake.

This event inspired and changed the artistic lives of my students by offering them the opportunity to see their peers work and to talk with some of the top theatre artists about their work. As a professor of design, I am honored to be a part of the Clambake; I take it as national recognition of my work as a theatre educator. Over time, the meetings with my peers and the discussions with the students offered me different points of view about scene design and influenced my teaching methods.

In 2006, for instance, a play I wrote was invited to perform at the Sibiu International Festival of Theater in Romania. As a result, I was unable to attend the Clambake. I called Betsy to excuse myself for that year, and she said, “Can you change the tickets? We need you here, because your input is different.” I was unable to change my tickets, but I was very touched. Betsy expressed the most simple and sincere welcome I ever received in this country. I felt that I belong to an artistic community where my contribution is appreciated, and I think that every participant at the Clambake, student or reviewer, feels the same.

I always saw the Clambake as an open class where students, teachers and theatre professionals meet and share ideas. The Clambake has shaped over the years the main trends of contemporary American theatre design.

There are other portfolio review events, such as the Young Designer’s Forum at USITT conferences, a similar portfolio review on the West Coast and some at the USITT regional conferences. But honestly, it is hard for me to imagine a replica of the Clambake the way it is at this moment—the creation of one of the best theatre designers in the world. And can somebody imagine the Clambake without Betsy Lee?

Born in Romania, Nic Ularu has extended international credits as theatre professional and educator. An OBIE Award recipient in 2003, he was the leading designer and curator of the U.S. national exhibit at the PQ 2007. He is an associate professor of theatre and director of the MFA design program at the University of South Carolina.