ST. LOUIS: A tragedy wouldn’t be a tragedy without tragic inevitability, but we probably wouldn’t keep staging the downer dramas of the Greeks and Shakespeare et al. if we didn’t hope to learn—or at least glimpse for a fleeting moment—how things might have gone differently.

As a new production of Sophocles’s Antigone opens tonight at the Upstream Theater in St. Louis, Mo., at a moment when that racially torn city has become a new flashpoint for very old American arguments about police violence, segregation and the right to protest, uncomfortable resonances suggest themselves: a dead body left untended for a disgracefully long time; a struggle between unyielding authority and transcendent conscience; a reckoning with the slow, often blinkered machinery of justice.

But, as director Philip Boehm puts it, “We’re not after one-to-one correspondence with the events in Ferguson—I think that would be wrong and inappropriate. The underlying issue of the play is a conflict between society’s need for law and order and an individual’s need to follow her conscience, but we’re also interested in exploring the psychological devastation all these social disasters carry with them. The wreckage is enormous and the collective psyche is scarred. Ideally, we want to ring bells that are deeper but that need to be rung.”

Boehm, who founded and runs the nearly-10-year-old theatre company, was in the midst of production and design meetings for Antigone—in a new translation by David Slavitt—when the unarmed Michael Brown was shot in Ferguson by police officer Darren Wilson on Aug. 9.

Demonstrations roiled the city and continue to this day; another police shooting of a young black man in St. Louis this week has only reopened the wounds (though the circumstances were different—the victim was armed, the cop was off-duty). Boehm says he immediately recognized that the issues raised by the play would unavoidably evoke Ferguson, and that the echoes should be addressed.

“Just as it would be inappropriate to press the play into service for a facile comparison, it also is an opportunity to spark discussion and amplify awareness,” says Boehm, whose theatre typically stages a three-show season comprised of U.S. premieres of international work and artful stagings of classics, and who has previously mounted Oedipus King and Oedipus at Colonus.

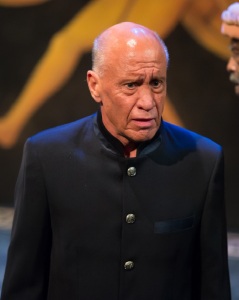

He says he’s invited Missouri elected officials to do talkbacks throughout the run of the play (it closes Oct. 26), and so far has lined up Shelley Welsch, the mayor of University City, Upstream’s St. Louis township. Says Boehm, “She’ll be up there talking with the actor playing Creon [Peter Mayer] about the challenges of ruling a polis.”

Of course, there’s no “ruling” going on in Missouri, strictly speaking—and that’s where Boehm hopes the inevitability trap can be sprung.

“I’ve often wondered what Sophocles would do here,” says Boehm. “In our society, the chance to vote and put people in office, and to get them out of office—we don’t live in Thebes or have a tyrant or a king; we have a chance to change the outcome, it’s not preordained. But there is a danger of it feeling preordained.”

He points to one scene in the play through which the light breaks, if only briefly.

“One of the moments I’m thinking about is when Tiresias comes in and tells Creon, ‘You’re the problem, and something terrible is going to happen.’ Creon turns to the chorus and says, ‘What do I do now?’ And they say, ‘Go and act.’ For a moment, I think he believes there’s a chance that maybe he’ll get there in time and correct his mistake.”

The question for Creon—who doesn’t yet know at that point that the condemned Antigone is beyond saving—is one we might ask ourselves as we consider the odds that justice will be served in Ferguson, and what that denouement will say about the American character: “Are we already too late?”