When the earthquake struck on April 25, 2015, the cast and creative team of Kathmandu’s One World Theatre Company were in rehearsal for Anna in the Tropics. We hurled ourselves down the stairwell and hugged the ground in the courtyard, which continued to roll beneath us. It was just the first of two 7.8-magnitude quakes that rocked the capital of Nepal, leveling buildings and killing more than 8,000 people.

At the time, plans were already underway for an original music-drama, The Macbeth Massacre, which would combine the talents of acclaimed international opera singers Roy Stevens and Annalisa Winberg with One World Theatre, a social justice-oriented English-language theatre company I founded in Kathmandu in 2011. Since then I’ve brought such plays as In the Red and Brown Water and The Laramie Project to Nepal, in collaboration with a core group of Nepali artists.

But the quakes halted all rehearsals and production plans. “Once the shaking stopped, we rushed toward our garden area and saw that our neighbor’s house had collapsed,” recalls associate costume designer Kalsang Lama. “Our compound walls were all gone. There were rumors that a bigger earthquake would come, and everyone felt a sense of hopelessness and fear. The first few months after the earthquake, life seemed very uncertain. Government help did not come. For almost six months, we lived in a tent.”

In response to this natural and cultural disaster, we postponed the Macbeth project and turned our attention to relief work. “We collected donations and ran a mess kitchen for the people,” actor Rajkumar Pudasaini remembers. “We distributed tents, medicine, and clothes to people suffering in remote valleys.”

Nepal’s recovery effort remained sluggish for months, further exacerbated by a crisis-inducing blockade of fuel imports. Managing everyday life in post-earthquake Nepal was difficult for everyone, but the arts community was hit especially hard. Many lost their livelihoods.

In the meantime, OWT found a new production to focus on: Arjuna’s Dilemma, a 70-minute contemporary opera by the American composer Douglas Cuomo, which had premiered at Brooklyn Academy of Music’s Next Wave Festival in 2008. The music-drama is based on text from the Indian epic the Bhagavad Gita and on the poetry of Kabir. OWT’s production will open on Sept. 2 with a gala reception to benefit the Patan Museum and the Kathmandu Valley Preservation Trust.

The story follows warrior Prince Arjuna in a legendary philosophical dialogue on the eve of the first conflict of a massive civil war. Like the Nepalese, who suffered through a recent brutal civil war and then the earthquakes’ devastation, Arjuna vividly imagines the coming destruction and wants “to stop my chariot”—a powerful refrain in the opera. Arjuna turns to his most valued advisor, Krishna, for advice.

Musically, Cuomo’s chamber opera brings the story of Arjuna’s Dilemma to life by fusing Western classical music with jazz and Indian classical music.

“The opportunity to work with an acclaimed international cast and production team bringing an original opera to Nepal, a country which has hardly ever experienced or produced one, was too exciting to pass up,” says writer and set designer Kurchi Dasgupta.

As most of the people involved in the production have never worked in the form before, the goal to bring together the combined expertise, traditions, and culture of all participants. Notes music director Jonathan Khuner, “I’ve been working 35 years in the operatic medium, but this project expands far beyond the boundaries of my existing métier. We are recruiting people from vastly different backgrounds and fields, for almost all of whom the content, the organization, and the actual opera production experience are very new.”

But there’s common ground to be found in musical improvisation, which is at the heart of both Indian classical music and jazz. Cuomo explains: “The Indian singer, tabla player, and jazz saxophonist each use their respective improvisatory traditions to reach for the ecstatic, the sublime, and the terror that make up the emotional world of this work.”

Nepali actors Rajkumar Pudasaini and Karma Shakya will play Krishna and Arjuna. Arjuna’s bow, Gandiva, is personified by the French ballerina Alizé Biannic, and Lord Krishna’s nature as creator and destroyer is portrayed through Kathak dance. As the director, I wanted show the human plane as it exists parallel to the divine plane. The ordinary life of Nepali people is gentle, family-oriented, and full of wonderful rituals and festivals.

In early 2016, the multinational team assembled in Kathmandu for in-person meetings with Nepali collaborators. The country was still struggling to rebuild almost a year after the quake. Rubble piles lay where buildings and ancient temples once stood. “The loss of Nepal’s priceless heritage is not only a loss for South Asia,” writes arts curator and production advisor Sangeeta Thapa. “Our history and cultural practices are a vast repository of wisdom, philosophy, beauty, and diversity that no other region in the world can rival.”

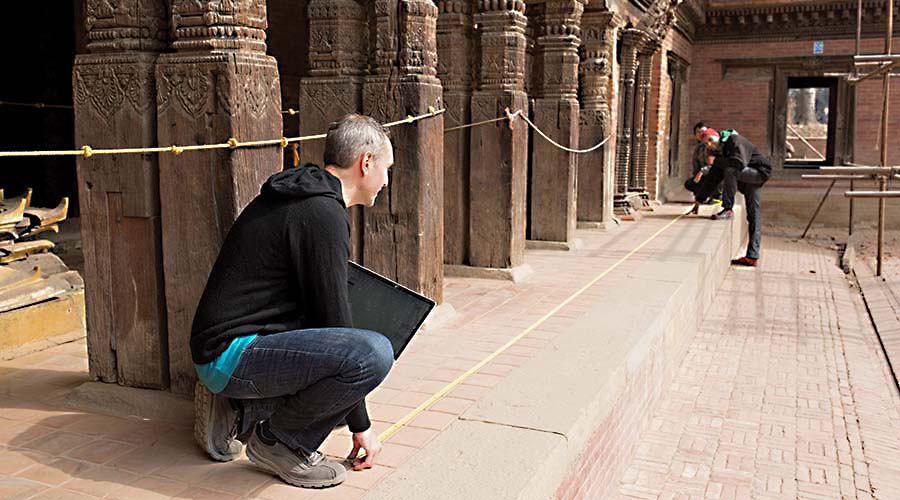

After scouting possible locations with government officials and historical architects, the team embraced an invitation to perform within Patan Durbar Square, a UNESCO World Heritage Site that suffered destruction in the quakes. The complex of Hindu temples, courtyards, and a palace museum holds deep spiritual meaning for the Nepalese. “The damage from the earthquake represents a national wound to which we hope to bring a small measure of healing with this work, which is so spiritual in nature,” says opera singer Annalisa Winberg.

After visiting Nepal, American designer Greg Mitchell began developing preliminary sketches for the set, lighting, and costumes in close collaboration with Nepali associate designers. “This is not just my own design, but a genuine collaboration…Isu [Shrestha], Kurchi [Dasgupta], Kalsang [Lama], and Rajkumar [Pudasaini] are all designers in their own right and we’re working to create something greater than any of us could do alone,” Mitchell explains.

The set’s structure will be made of bamboo, an affordable and plentiful material in Nepal most often used in building scaffolding. Since Arjuna’s Dilemma will be staged within damaged, culturally significant sites, bamboo serves both an aesthetic design purpose and the practical structural need to shield the fragile surrounding architecture. “I have made a mission out of using the funding resources we have available to hire Nepali artists and craftspeople,” Mitchell adds. “I’d rather see the money go to people making art than invest in costly building materials.”

The set will also include a deep staircase and multiple raised levels, with sculptures commissioned from local Nepali artists. Mitchell invited the cast and collaborators to create personally meaningful shrines and memorials to go in the bamboo structure.

The collaboration between artists of different backgrounds has stirred great pride. “The aesthetics of the ancient Eastern background with the fusion of Western opera and Eastern music is a rare spectacle, to say the least,” explains production manager Isu Shrestha.

Singer Roy Stevens admits that he worried the project would be see by the Nepali people as a naïve attempt to combine cultures. He needn’t have worried. “On the contrary, the response has been that of great appreciation, even from the scholars at the Sanskrit University—a sense that we are honoring their culture,” Stevens says. “They, and we, believe that providing necessities following a disaster is paramount, but not enough. Our production of Arjuna’s Dilemma, instead, is a gift for the soul of Nepal.”

Deborah Merola, Ph.D., is the director of Arjuna’s Dilemma and the artistic director of Kathmandu’s One World Theatre company. For more information, visit www.OWTNepal.org.