The power of positive thinking is getting a puppet-infused homage specifically designed for the age-four-and-up set. Making its world premiere this month at Virginia Repertory Theatre, in Richmond, The Little Engine That Could is the work of some of the city’s most experienced theatre artists, including a well-traveled puppeteer/puppet builder; a company leader who moonlights as a Sunday school teacher; and an actor with a sideline in the Navy Reserve.

Running July 7-30, The Little Engine That Could is billed as an adaptation of a 1906 sermon—about which more later. But most audiences will likely consider it a dramatization of the beloved 1930 children’s book about a diminutive engine who tows a stranded train over a mountain while determinedly repeating the motto, “I think I can.” Bruce Miller, who was Virginia Rep’s founding artistic director until 2016, when he segued to his current post of founding producer, said that tale has always been a favorite. “I know with myself and with the journey I’ve been on over my 66 years, I’ve come to rely on the power that positive thinking has,” he said.

The story surfaced as a natural choice when Miller was brainstorming potential collaborative projects with Heidi Rugg, founder of the Richmond-based touring company Barefoot Puppet Theatre. In the book, the stranded train is full of talking toys, a situation “that naturally lends itself to adaptation for puppetry,” said Rugg, who has worked at the Eugene O’Neill Theater Center, in Waterford, Conn., and the Puppets Up! International Puppet Festival in Almonte, Ont.

When Virginia Rep associate artistic director Chase Kniffen took over supervision of the fledgling musical—he is directing—he recruited Scott Wichmann to write the book and lyrics and Jason Marks to supply the score. The two “have a really great rapport in lyrics to songs, and I knew Scott would bring his quirky sense of humor to it,” Kniffen said.

One of Richmond’s most acclaimed actors, Wichmann was also a fan of the Little Engine narrative. “The story is bulletproof,” he pointed out. “It’s small enough to be a literary gateway drug for kids on their way to larger narratives. It has a motivational dimension to it. And then it also has this ‘I think I can’ mantra, which is famous.”

The motivational dimension had particular resonance for him. In 2009, when he was already in his mid-30s, Wichmann joined the Navy Reserve, inspired in part by the revelatory experience he had had working out with Seal Team Physical Training, a fitness program whose Richmond-raised CEO, John McGuire, “radiated ‘I think I can’ and radiated ‘I think you can too!’” Wichmann effused.

Since his enlistment Wichmann has juggled theatre gigs and Navy work, first as a logistics specialist and more recently as a mass communications specialist. In 2012 he was posted to Afghanistan, where he helped the Army dispose of unserviceable property on forward operating bases; shortly after returning to Richmond, he played Leo Bloom in Virginia Rep’s The Producers. Subsequent Navy postings have sent him to Djibouti, and more recently to the decks of the U.S.S. Dwight D. Eisenhower off the South Carolina coast.

Jason Marks, an actor and composer, is known for scoring the frog-prince musical Croaker, which has been staged in New York. (It will open at the Riverside Center for the Performing Arts, in Fredericksburg, Va., in August.) He and Wichmann wrote the Virginia Rep children’s shows Hiawatha and Have You Filled a Bucket Today?: The Musical!, and he played Max Bialystock in that Virginia Rep Producers. Marks appreciated the fact that the succinct Little Engine story offered room for creative elaboration.

“The nice thing about the story is that it’s so brief,” Marks said, and that “all the versions are different,” meaning screen adaptations. “So we really felt we had liberty to make it our own story.”

The two creators wanted to ground the tale in a naturalistic world, so Wichmann mulled over potential equivalents to the engine’s mountain-scaling trek. Rather than “the physical act of moving something from point A to point B, it spoke to me that the parallel was actually lifting other people up,” he said.

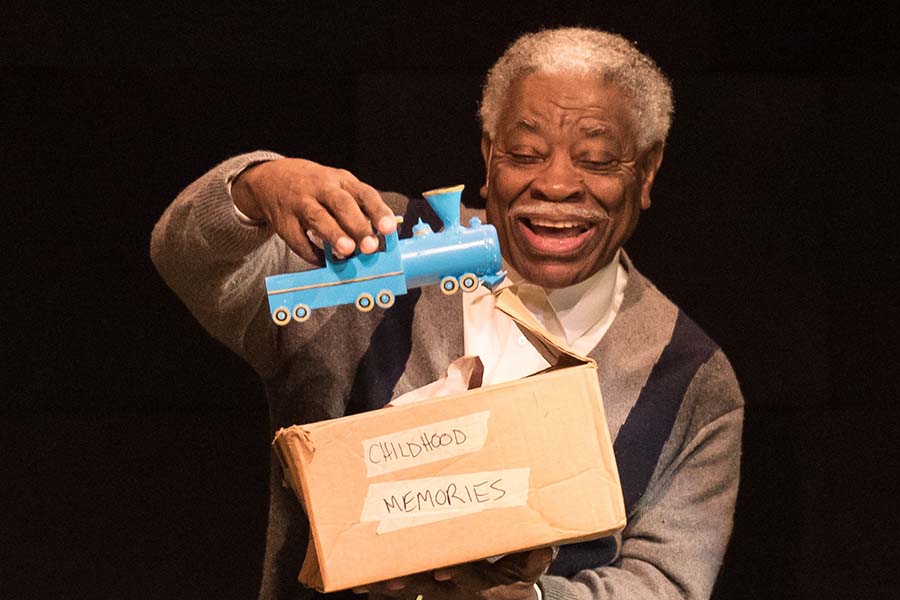

So he wrote a new frame tale about a young girl, Ginny, who encourages her dispirited grandfather as he prepares to leave his own home and move in with family. When a discovery during the packing process prompts him to recount the Little Engine story to Ginny, who uses a wheelchair, she seems to transform into the title character.

The new additions to the story reinforce “the idea that the smallest among us are able to lift up and spread positive energy to those who should be strong,” said Kniffen. He also liked the show’s consequent message of female empowerment.

Indeed, a girl-power message was arguably present in the 1930 original, which refers to the title character as “she.” But, as Miller discovered when he was doing initial research for on the project, the roots of the persevering-locomotive trope go back further. According to scholar Roy E. Plotnick’s chronicle of the tale’s tangled legal and cultural history, the I-think-I-can mantra was linked to the noises of a toiling locomotive as early as 1902. A recognizable version of the full story—with non-gendered engines—appeared in a 1906 New York Tribune article about a sermon that Rev. Charles S. Wing had delivered to a Brooklyn church.

When Miller learned about Wing’s version, he was thrilled. “I thought, ‘This will be a really positive thing, that this originated as part of a sermon!” he said. Miller, who teaches Sunday school at Presbyterian churches in his off hours, was one of the cofounders of Richmond’s Acts of Faith festival, an annual showcase of plays with spiritual or ethical themes. But though it was a plus for him, he noted that “in today’s highly political world, saying that something originated as part of a sermon is a real turn-off for a lot of people. So we’ve had to explain, ‘No, it’s okay!’ That was an eye opener for me.”

Of course, embracing Wing’s 1906 version has another benefit, unrelated to religion. “By going back to the original source material, we’re going back to the public domain,” Miller admitted. “And that is a good thing.”

Celia Wren is a former managing editor of American Theatre.