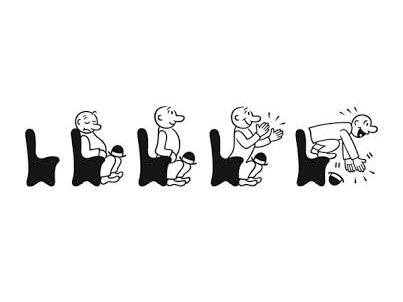

Long before the age of emojis, decades before even the thumbs-up/thumbs-down metric of film mavens Siskel & Ebert, San Francisco Chronicle readers were bequeathed their own shorthand consumer metric for films and plays, the so-called Little Man. For a black-and-white cartoon with a diminutive name, Little Man has loomed especially large and long over Bay Area arts. Created in 1942 by late cartoonist Warren Goodrich, he is a star rating system personified in the form of a bald white man in a theatre seat with five possible positions: In the first, he is either leaping out of, or crouching on the edge of, his seat, clapping so ecstatically hard that his bowler hat has been knocked to the floor, which obviously means the Chronicle’s critic thinks your movie or show is a must-see; in the next, he applauds enthusiastically, still a strong recommendation. In the third (and most contested) pose, he sits crisply at attention but does not clap, which connotes some liminal range between positive interest and polite indifference. The last two—nodding off or absent altogether—speak for themselves, albeit with exaggerated rudeness.

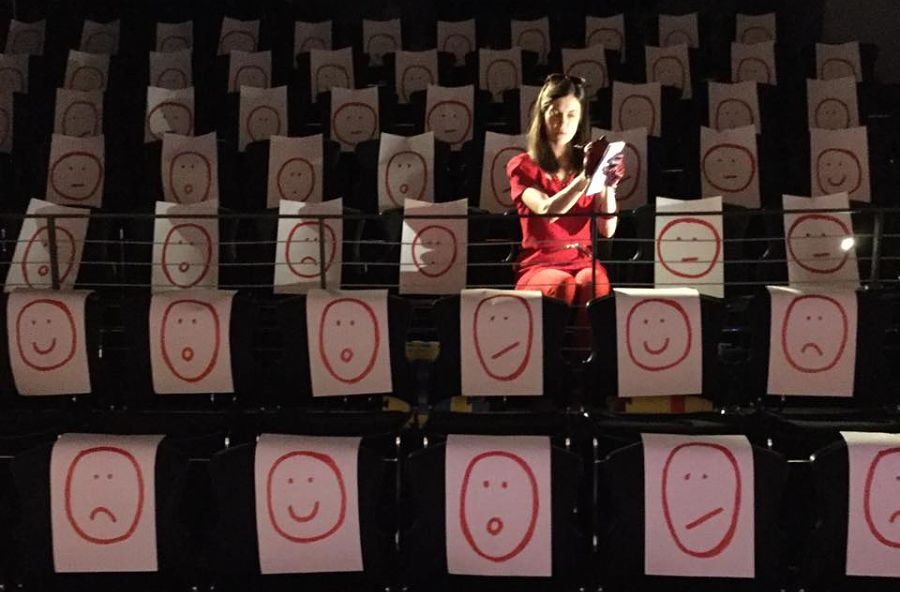

“It’s a very visceral icon, and always has been—it’s really buzzy,” says Pam MacKinnon, who took over as artistic director of American Conservatory Theater in 2018. Those are the nicest things MacKinnon can say about the Little Man, though. As she attempts to create a forward-looking organization based on principles of equity, diversity, and inclusion, and as she brings in a wide range of national artists to ACT to write, direct, and perform, she has found herself increasingly questioning the relevance of this nearly-80-year-old cartoon as an avatar for contemporary Bay Area theatregoers.

“I don’t use this term lightly, but I think it’s true in this case: It’s a white supremacist icon,” says MacKinnon. She recalls the response of playwright Lydia R. Diamond, whose play Toni Stone begins performances at ACT on March 5, when she saw the Little Man: “Whoa—that guy has a jockey on his lawn.” It’s an image “made in another time, and very particular to that time,” says MacKinnon.

To be clear, MacKinnon doesn’t expect the Chronicle, or theatre critics more generally, to only give good reviews or to do her marketing for her. But she would hope that the local press could be a partner in “figuring out how theatre can punch through and get attention in this market. I’m really trying to open this theatre up and say, ‘This is your theatre, San Francisco.’ What is San Francisco? It’s 30 percent Asian, it’s very young, it’s Black as well as white.” Zooming out, she concludes, “This is a really exciting, dynamic time, and the field is talking about big stuff. I want my guest artists to feel welcomed, and this icon from the 1940s gets in the way of my ability to host them with a clear conscience.”

Asked about the Little Man, the Chronicle’s senior editor for arts and entertainment, Robert Morast, concedes that he’s “polarizing.” Morast, too, sees the pros and cons: “I hear all the time that readers look to the Little Man, and from my standpoint, that’s good and bad. I love it as a branding thing, and for a lot of people it seems hard for there to be a review and not have a rating.” On the other hand, the Little Man only appears with reviews for film and theatre, not for classical music, opera, or fine arts—a vestige of “longstanding rules and traditions,” Morast explains, “that are worth looking at. I totally understand the criticism.”

Lily Janiak, the Chronicle’s chief theatre critic since 2016, shares some of the local ambivalence about the Little Man, not least because he “is not me in very visible ways, and he looks like he somehow has authority over me.” But she nods to his pop-cultural appeal, sharing a popular anecdote about how, when local native Darren Criss moved away from the area, he was surprised to find that not every city’s newspaper had a Little Man with their reviews. “It’s a nice, clear guide for consumers,” Janiak concedes, “not just whether you should go to the show but whether you should keep reading the review or not. Which is where it gets tricky for me.”

Indeed, leaving aside the specific issues of the Little Man as a cultural signifier, there’s the question of ratings systems in general. Do they simply reduce critics’ work to math? Do they encourage or discourage readers from, well, reading? They are not universally used, even in major markets: In New York City, only Time Out New York, New York Post, and New York Daily News use star ratings, and Chicago Tribune does as well. And unlike in San Francisco, these are not longstanding customs: Time Out only began giving stars in 2006, and the Tribune “some time in the aughts,” according to critic Chris Jones, as “one of many so-called customer-friendly features introduced by our capitalist owners.”

“It can be very handy for readers, as a form of immediate shorthand,” says Adam Feldman, Time Out NY’s theatre editor. “It can be frustrating when you want to make a more complicated point or have a more complicated reaction, and you have to quantify it somehow.” What’s more, he adds, “It’s human nature that people are more likely to read a review that is very positive or very negative. The three-star review is less likely to be read.”

Jones has “made peace” with the Tribune’s star rating system because, as he puts it, “It gives enormous power to a four-star review. Anyone can immediately grasp that this is a must-see. I have found over the years that this can help the shows that really need it.”

Jasson Minadakis, artistic director of Marin Theatre Company, can testify to the local influence of the Little Man’s most superlative stance.

“It’s a double-edged sword,” says Minadakis. “When you get the top-rated one, where he’s standing on the leg of his chair—bad behavior in the theatre, by the way—that definitely affects ticket sales. It’s not a negligible thing for my company. It’s literally triple the ticket sales that would happen otherwise, amounting to tens of thousands of dollars.”

Any rating below ecstasy, though, is another story. “The second one, the applauding man, can work if the headline is good,” Minadakis says. “The staring guy and below will halt single-ticket sales.” Says his colleague, Kate Robinson, Marin’s director of ticketing and communications associate, “I don’t think it’s teaching audiences to engage in a human way with a show. It’s teaching them to come into our theatre and have a very superficial response.”

That’s where a thoughtful critic ought to come in, right? Janiak admits her ongoing issues with the Little Man—she particularly objects to the sleeping icon, not only because she would never doze off at the theatre (heaven forfend!) but because she is more likely to give a two-star rating to show that enrages her than one that bores her. But short of suggesting such half-joking alternatives as “a unicorn jumping over a rainbow,” she has bigger fish to fry than the Little Man.

“Among all the battles I could fight, that is not the charge I’m leading,” says Janiak. “Trying to say that even a middling review of a small company is worthwhile—that’s the hill I’m going to die on. I actually feel I have support for that there; I’m not fighting for my existence.” Her challenge, in an age of declining attention spans and click metrics, is to “write in such a way that you have to read the article, even if you only see the headline, deck, first sentence—and the Little Man.”

Interestingly, when Soleil Ho was hired last year as the Chronicle’s food critic, she successfully lobbied to have all ratings taken off her reviews—a major thrown gauntlet in a very Yelp-ified, everyone’s-a-critic realm. Might this also offer a possible green shoot of hope for the endangered cause of nuance in the age of tl;dr? Janiak says she plans to confer with Ho about this policy, adding hopefully, “I would be pretty okay just being able to express myself with words.”