In 1971, Willa Kim designed costumes for Weewis by Margo Sappington for the City Center Joffrey Ballet. The ballet marked her introduction to a then brand-new fabric called spandex, which had only been invented recently. At that time, there was stretch-able fabric, but it didn’t bounce right back—it didn’t have “memory.”

“Willa realized that it would be a great dance fabric,” recalled Richard Schurkamp, a friend and executor to Kim’s estate, who knew her for almost 40 years, until her death in 2016. “As we all know now! Everybody in the world, the dancers and people who do yoga or go to the gym or anything wear this fabric.”

Kim also quickly discovered that spandex could be painted, and a whole world of painted stretched costumes opened up for her. Schurkamp worked with her on the 1995 Broadway musical Victor/Victoria. He remembers the dance number “Le Jazz Hot!,” which began with three men, purportedly in a jazz club, playing piano and trumpet and trombone. They danced with their instruments in three-piece suits that weren’t suits at all but single units crafted of spandex; the actors simply stepped into them and were zipped up the back. They were silver gray with stripes of red up the side, and when they moved, the jacket didn’t pull away from the vest, and the vest didn’t separate up from the pants. It was a complicated construction, and it was all Kim.

“It seems a very quintessential Willa costume to me—the zipper was hidden, and you couldn’t ever see that it wasn’t a three-piece suit,” said Schurkamp.

What set Kim apart from a lot of other designers, Schurkamp feels, was her wit. There was always humor in her costumes, he said. Not that they were goofy or overtly funny, but there were slight touches of humor. One always knew when they were seeing something by Kim, he said, because there were often clever little jokes in the design.

“In the world of theatre design, Willa Kim pioneered the use of synthetic stretch materials, and related dyeing techniques, that facilitated the movement of performers,” said costume designer Bobbi Owen, author of the 2005 book The Designs of Willa Kim. Owen has been working on an exhibition of Kim’s work for the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts in New York City, “The Wondrous Willa Kim: Costume Designs for Actors and Dancers,” which was originally slated to open on May 20 but has been postponed due to the coronavirus pandemic.

Kim had an unusual gift for designing whimsical costumes by using extraordinary combinations of color and texture, Owen said. Regarded as one of the foremost designers for dance, with nearly 200 productions to her credit, she was equally accomplished at designing plays, musicals, and operas.

“Dancers loved her,” said Schurkamp. “They more than anyone understood what she was doing because they’re so aware of their bodies.”

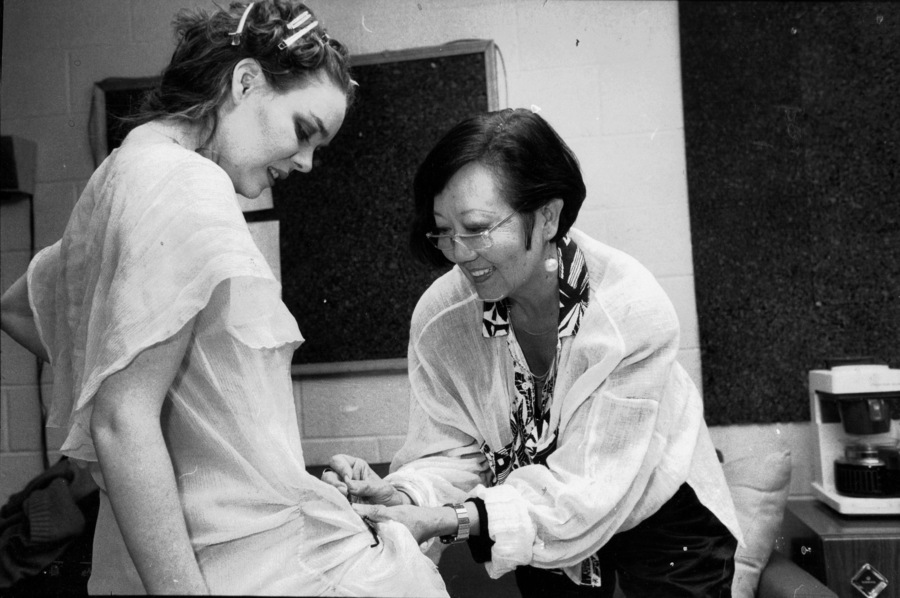

Kim would start with the performer’s body. Everyone, whether they were the member a dance company, a singer in a Broadway show, or an Oscar-winning star, would start the process with a visit to the beautiful studio she kept at her New York City apartment. She would get them to strip down to their underwear, and then she drew their figure, drew the silhouette of their figure, and took very precise measurements. She would then know intimately anything that might be considered flaws in their figures that could be downplayed, as well as assets that could be accentuated. She always designed her clothes with that in mind. It was as if she were sculpting her costumes on actors’ bodies, or painting them with fabric to make them look their absolute best.

Another key part of her process: watching performers move. “She would not design costumes for actors or dancers without first watching them move in rehearsal, so that her costumes both fit and moved in harmony with their bodies,” said Owen.

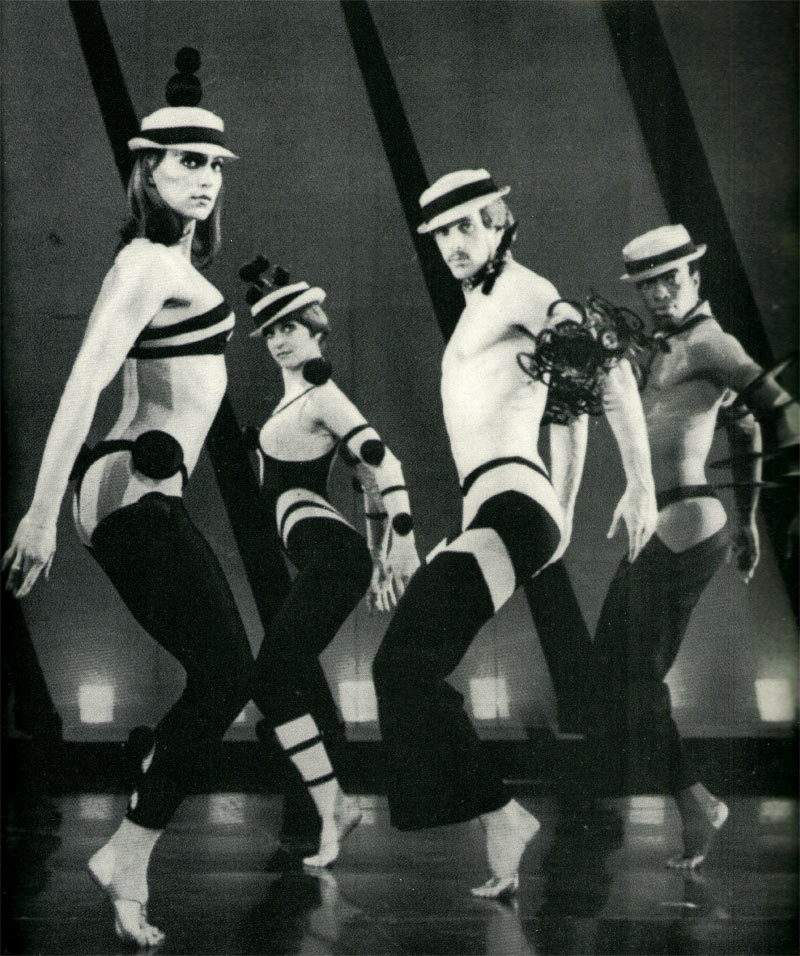

In the 1978 Bob Fosse musical Dancin,’ there was a number called “Percussion,” a kind of calypso dance for which Kim designed very sexy costumes. They had soft balls and ball fringe on them, affixed in odd places, like on the top of the dancer’s head or on the point of their shoulder or the point of their hips; they were all attached so that the costume vibrated and bounced, creating a sort of chain reaction in the balls and accessories. Fosse won a Tony for his choreography, but Kim’s work was doing a lot of the work to put his dances across (her costume design was nominated).

Similarly, for an Elliot Feld ballet with a solo dancer, Kim designed gloves with strings of beads coming off the ends of the fingers. When the dancer moved her hands, she would flick her wrist and the strings of beads would fly out. A small movement of the dancer’s fingers became more extreme movement because of the costume. Feld and Kim would collaborate more than 50 times.

“You could hand her three pieces of black velvet, and at a glance she would be able to tell which black had a little more green and which had a little more red in it,” said Schurkamp. “She was very exacting about colors.”

Kim understood the psychology of color and the placement of color onstage and on the body. Most people also know her for her use of paint on costumes. She wasn’t afraid of strong colors and of things that maybe weren’t so lovely standing in the fitting room in terms of color but would make a really strong picture on stage.

In 1976’s Under the Sun by Margo Sappington, inspired by the paintings of Alexander Calder, Kim accentuated the movement with a vibrant use of colors.

“In one costume, there’s a yellow arm or a blue leg, and a big stroke of red down one side of a costume,” said Schurkamp. “I’m not sure that I am describing the actual costumes, but I remember that being done because one of the dancers had an arm extension that Willa wanted to feature.”

“She started out wanting to be an illustrator,” said Sally Ann Parsons, owner and creative director at Parsons-Meares, Ltd. who first collaborated with Kim in 1972. And could she draw! Seen today, her sketches look effortless, as does her use of color. She was a careful researcher, though she never exactly reproduced any period painting or photograph, and she paid great attention to detail, said Owen. Kim studied art at Los Angeles City College and received a scholarship to the Chouinard Art Institute, now the California Institute of the Arts (a.k.a. CalArts). After graduating, she worked with costume designers Barbara Karinska and Raoul Pène Du Bois at Paramount Studios.

She collected several awards in her seven-decade career as a costume designer. Her two Tonys were in 1981 for Sophisticated Ladies and in 1991 for The Will Rogers Follies. She was also nominated in the same category four other times: in 1975 for Goodtime Charley, in 1978 for Dancin’, in 1986 for Song & Dance, and in 1989 for Legs Diamond. She received the 1999 TDF Irene Sharaff Award for “Lifetime Achievement in Costume Design.”

“I was always encouraged to be an artist,” Kim had said in an interview with Linda Winer, host, theatre critic, and arts columnist for Newsday in 2002, for Women in Theatre series by CUNY. “And this was what I was supposed to do.”

Utkarsha Laharia is a Goldring Arts Journalism graduate student at Syracuse University. Russell M. Dembin contributed reporting to this piece.