In the northwestern Chicago neighborhood of Albany Park, a three-story warehouse stands on an east-west thoroughfare, surrounded by residences, small businesses, and chain stores such as Family Dollar. Constructed in 1929, the building still has “Fernstrom Fireproof Storage” engraved on its handsome façade. But the interior has been transformed into a courtyard-style apartment complex for Port of Entry, a world-premiere immersive production by Albany Park Theater Project (APTP) and Third Rail Projects.

In Port of Entry, 26 young performers portray immigrants from around the world who live in Albany Park, one of Chicago’s most diverse communities. At each performance, the cast guides 28 audience members through custom-built homes, inviting them to handle treasured objects, play games, and even eat and drink together as they share their characters’ stories.

Since APTP was founded in 1997, its critically acclaimed teen ensemble and adult artistic team have specialized in devised works based on true stories of immigrants and first-generation Americans, Chicago youth, people living in poverty, and others whose voices have been marginalized. The company also focuses on social justice and offers college preparation support for its ensemble members, most of whom come from immigrant families in Albany Park.

In 2013, APTP co-executive director David Feiner and associate director Maggie Popadiak attended Then She Fell, Third Rail Projects’ acclaimed immersive production inspired by the life and writings of Lewis Carroll, which would eventually run for seven and a half years in Brooklyn. They were captivated by Third Rail’s work and reached out to see if some sort of collaboration would be possible.

“APTP has always been focused on what the audience experience is,” said Feiner. “In Third Rail, we saw a similar attention and dedication to making the audience feel like they were essential and they were part of something and building a connection.”

When Feiner invited Jennine Willett, co-artistic director of Third Rail Projects, to attend APTP’s production of God’s Work at the Goodman Theatre in April 2014, Willett was “completely and totally blown away.”

“The company was so courageous, so physical,” she recalled. “I became a super fan of APTP after that show.”

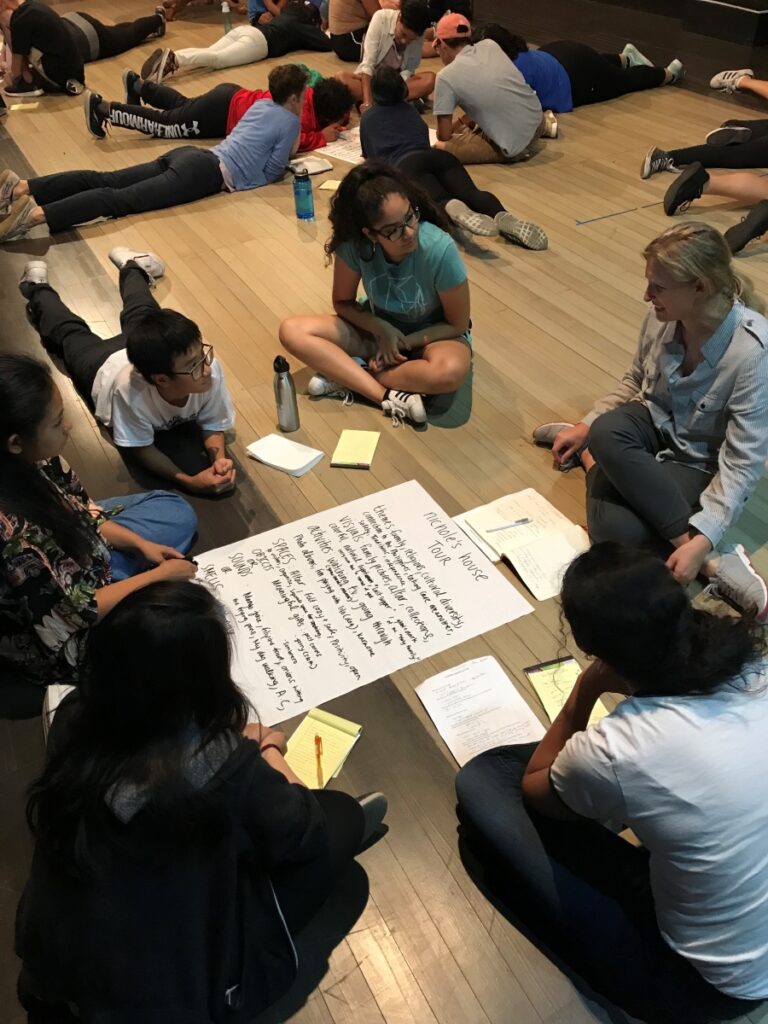

The two companies formed a modest plan to collaborate on a one-week workshop with APTP’s youth ensemble in the summer of 2014. “It was really thrilling to see the teens enter into the immersive work,” Feiner said of that week. The workshop went so well that participants created an hour-long first draft of Learning Curve, which APTP and Third Rail later produced as a full-length piece in 2016.

Featuring an ensemble of more than 30 high school students, Learning Curve provided an inside look at the daily lives of students in Chicago Public Schools. The production was named one of the Chicago Tribune’s top 10 shows of 2016 alongside works from the likes of the Goodman, Steppenwolf, and Victory Gardens. Learning Curve extended its run several times, ultimately playing for five months.

When APTP and Third Rail first started working together, their other big idea was to set a show in an apartment building. In 2018, they began developing Port of Entry, which Feiner described as APTP’s most ambitious production to date. Feiner, Popadiak, and Willett are part of a team of nine co-directors on the project, along with Roxanne Kidd, Marissa Nielsen-Pincus, Steph Paul, Devika Ranjan, Edward Rice, and Miguel Angel Rodriguez. The devised production is based on extensive interviews with local residents, with some scenes inspired by the families of ensemble members.

“One of the defining elements of Albany Park since the 1970s or ’80s has been that it’s a place where people from all different parts of the world live side by side in the same building,” said Feiner, who is also Port of Entry’s producer. “Because of the changing courses of history, globalization, and the conflicts in Asia and in Latin America that displaced people, folks who never would have crossed paths are now next-door neighbors.”

Visits to the homes of ensemble members and Albany Park residents were key to developing the script. “We were able to ask questions, gather stories,” explained Popadiak. “Everything that we do is recorded. We transcribe it word for word, and we treat it like text, and so it just becomes the record of Port of Entry.”

In addition to sharing their stories during home visits, APTP’s teens helped to develop the script. Cast member Ari Salgado, who is Mexican American, has been working on Port of Entry since 2019, and they play the mother in a scene about a Mexican American family.

“Developing my character was a lot of fun,” said Salgado, “because I got to put a lot of my mother—her antics or whatever—into the character, as well as seeing myself in my peers, because they’re playing kids my age. Being able to include my language, my cultural stuff, into that home was really fun.”

“We’ve often told stories about home and objects, so APTP has a devising process that often starts with an open-ended question or prompt,” said Rodriguez, co-executive director of APTP. In one exercise, students brought objects from home that they might put in a time capsule and shared stories about them, finding ways to connect their own experiences with previous interviews to create a cohesive scene.

In addition to the directors and cast, many of Port of Entry’s designers have also been involved since the early days. Similar to the development process for the script, the designs were informed by visits to ensemble members’ homes. “We identified what culture they’re part of; they told their stories about how they have lived and where they live now,” scenic designer Scott Neale said. “We took pictures and videos, and then we just had this giant archive of these worlds, which is essentially what this entire thing is about—their lives.”

Though the pandemic delayed the show’s opening, the team kept working on Port of Entry. Neale used the extra time to build a scale model of the three-story set, and props and immersive aesthetics designer Ellie Terrell continued to gather ideas from ensemble members during Zoom meetings.

At long last, tickets for Port of Entry went on sale in June, and it was immediately clear that there is an appetite for this type of work. The first block of tickets, for dates through Aug. 12, sold out within days, with additional performances scheduled for October through December. The goal is for the run to be open-ended and extend into 2024.

When I saw the first preview performance in mid-July, I was struck by the intricate craftsmanship of the physical spaces. Despite the occasional whiff of fresh paint and the last-minute adjustments in progress, the apartments look like real homes in Chicago—complete with radiators, bricked-over fireplaces, and kitchen doors that lead to tiny stairwell porches. Moreover, each space feels like a unique home inhabited by an actual family, due to the detailed work of the production team, including Neale, Terrell, Elizabeth Mak (lighting and projections designer), Nicole Lang (associate lighting designer), and Trina McGee (director of production).

“Making the homes as realistic as possible included primarily shopping in Albany Park—going to thrift stores, going to a Filipino grocery store, going to a Mexican grocery store,” said Terrell, “just staying as culturally specific as possible, but then also with the ability to shift into a more surreal or magical space as the story necessitates.”

One memorable example is the aforementioned apartment of a Mexican American family, who invite audience members to play Lotería, a traditional Mexican game similar to bingo. The bright lighting, warm colors, positive affirmations on the walls, and family photos and books lining the shelves create a palpably welcoming atmosphere. This cheerful scene is eventually interrupted by a phone call delivering devastating news that throws the family into chaos. The work of sound designer and composer Mikhail Fiksel (who won a Tony for Dana H. in 2022) and associate sound designer Noel Nichols is chillingly effective here.

Because multiple scenes take place simultaneously throughout the building, the actors must time their performances to be precisely in sync with the technical elements. “The stage manager presses ‘go’ once, and the whole show happens after that,” said Lang. “So really, the timing between all of the departments has had to be so, so specific.”

In this sense, Port of Entry functions more like a dance piece than traditional theatre, where stage management responds to the performance in real time, Fiksel explained. “If we do our job correctly, that’s not apparent to the audience, but everything is actually locked in. In order for this piece to continue to move that way, honestly, every second is accounted for.

“The performers are doing this crazy balancing act of engaging with a human, who is a complete unknown, and dancing and changing costumes and doing all this stuff—while being aware that they’re at exactly four minutes and 35 seconds into that scene, which means that they have two minutes and 15 seconds left. So part of the design becomes not just art, but also logistics.”

The young cast members take on these challenges with admirable poise and give moving performances. Each night, the audience is divided into small groups that move through the building together, visiting four main homes as well as smaller scenes within each, resulting in a different experience for each attendee. Actors engage with audience members throughout, sometimes one-on one, without the comfort of a fourth wall.

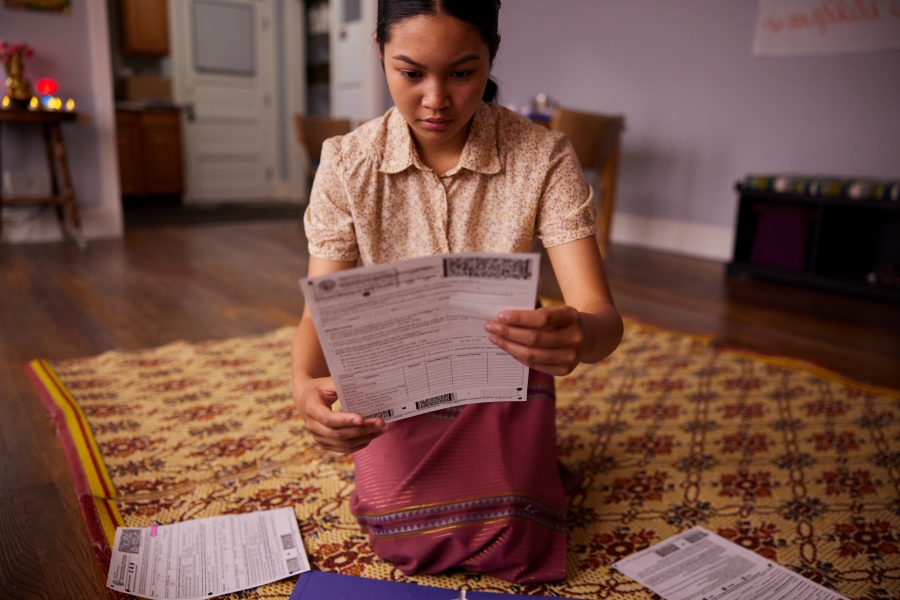

First-generation Filipino American Beatriz Gigante said she feels a deep connection with their character, whose story is based on the family of another ensemble member. This family is part of the Karen people, displaced from Myanmar by war.

“We got to take inspiration from the transcript of the interview in their home,” said Gigante, “thinking about the memories that the mother has of being in the refugee camp versus being here, like being scared to open the oven or not using a bed right away because they were still used to sleeping on a straw mat. Every time that I do my scene, it’s very hard not to cry, because it reminds me of my parents and them trying to navigate their life when they first arrived here in America.”

Maidenwena Alba, also a first-generation Filipino American, is an APTP alum who was in Learning Curve and God’s Work and has returned as a rehearsal captain and swing for Port of Entry.

“This show feels more personal,” Alba said. “Learning Curve was also very important, but in Port of Entry, you’re stepping into these people’s homes, where this is their safe space. This is where they’re vulnerable. I really found my heartstrings being pulled in this show.”

Sara Romero, who is Mexican American, had the opportunity to meet with the Polish woman who inspired one of the characters she plays and hear her story firsthand. “Being able to see your neighbors in your character was so eye-opening,” said Romero, “and being able to put my own input into this character, as well as using her wisdom and her life and having her put herself into this character that I am embodying.”

All five cast members I spoke with strongly believe that the arts, and especially immersive shows like Port of Entry, have great potential to spread awareness about social issues.

“These stories come from immigrants and people who are minorities, and I feel like we bring light to a lot of situations,” said Lesly Aguirre. “Sometimes people are scared to talk about it, but I feel like APTP helps them be comfortable enough to talk with other people about their situations.”

“Art makes education accessible,” added Salgado. “Maybe you can’t sit down and read a book about the issue, but maybe you can sit down for two hours and participate in a show.”

“It really can influence someone to be like, ‘I want to research more on this,’ ” said Gigante. “I know that for my home, I was really passionate about it, and I ended up writing a project about the Karen civil war. APTP and this theatre’s directing, this ethnography, has really taught me more than I feel like my school system has even taught me, honestly.”

Port of Entry co-directors Rodriguez and Popadiak can attest to the legacy of APTP in their own lives: Both grew up in the program and now work for the company.

“I think that APTP and this show, in particular, is a really good example of how APTP becomes—for all of us who are ever in it, including adults—a place where you find, you develop, or we foster pride in all aspects of your story,” said Rodriguez. “In a time in which being ‘other’ continues to be attacked across the world, APTP becomes a beacon of hope for what communities could look like outside of Albany Park or outside of a theatre company like this.”

For me, the opening image beautifully sums up Port of Entry: Alone or in small groups, new Chicagoans enter their apartment building for the first time, toting luggage and wearing costumes from many different cultures and eras (designed by Izumi Inaba and based on extensive historical research). They each pause on the threshold of the courtyard with pensive, nervous, or hopeful looks in their eyes—then resolutely proceed on to a new life.

Emily McClanathan (she/her) is a Chicago-based writer whose work has appeared in the Chicago Tribune, Chicago Reader, Playbill, TheaterMania, Theatrely, and more. She is a 2020 National Critics Institute Fellow.