Three-time Tony-winning actor-dancer-choreographer Hinton Battle died on Jan. 30. He was 67.

“Hinton was dynamite,” Debbie Allen, the Tony- and Emmy-winning star of TV’s Fame, told me. “Dancing dynamite, because he exploded onstage. It was where he was meant to be.”

“There was nothing like him,” added Phylicia Rashad, the acclaimed actor and director and current dean of the Chadwick A. Boseman College of Fine Arts at Howard University. Actor Keith David recalled that he met Hinton at Julliard, and the two of them snuck into the dance juries, hungry to see the other students perform. When Hinton danced with Shirley Black-Brown to “Wind Parade,” Keith said, they would fly through the air from different parts of the room and meet in the middle, having “the synchronicity of Busby Berkley. The best dancing I’ve ever seen. We all knew we were witnessing talent extraordinaire!”

As Denise Saunders-Thompson, former co-curator of Dance Theatre of Harlem and currently assistant dean at Howard’s School of Fine Arts, put it, “He was always outside the box and enjoyed life to the fullest. He entered relationships that way, always wanting life and light. I loved that about him.”

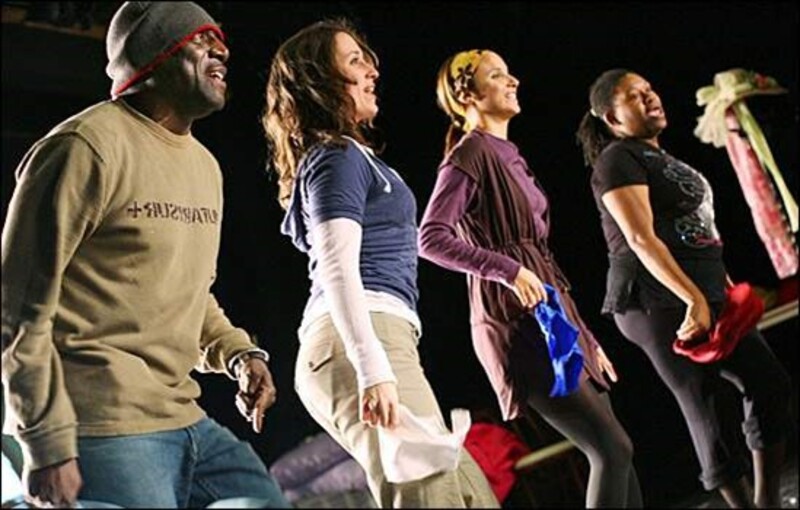

Hinton never stopped growing as an artist. Besides performing, he excelled in creating choreography, music arranging, directing, and producing. I met Hinton when he directed a production of my musical Respect: A Musical Journey of Women at the Gem Theater in Detroit in 2007. He created magic and color and light in a way I’d never seen.

Several years later, when my musical Sistas was up at a New York City festival, he came up from Atlanta to see it. I sat next to Hinton and, as the show ended and lights went up, waited for what I was sure would be his harsh but true notes and comments. (You don’t get three Tonys without having high standards.) He just looked at me and said, “Dorothy, this is what we need on the stage.” He and Bill Franzblau became the show’s producers, and Sistas played Off-Broadway for nine years until Covid shut everything down.

I am writing this tribute as an appreciation for someone who touched my life dramatically, and for multitudes of audience members, and for all he has done for countless artists in various media.

“I met Hinton right after I arrived in the city,” Debbie Allen told me. She was to be a member of George Faison’s Universal Dance Experience, in which Hinton’s sister, Lettie Battle, was a principal dancer. Hinton came to rehearsals after hours of classes at the American Ballet Theatre. “He arrived in his jean shorts, wild hair, and those big, tawny platform shoes we all wore. He was so joyful,” Allen told me. Then they appeared together in Raisin, the musical adaptation of A Raisin in the Sun. Don McKayle cast them as dance partners. “We were killing it,” she continued. “We were doing all these lifts and spins and almost acrobatic things, and then one day Hinton said, ‘I’m tired of picking you up. I’m leaving the show.’” He could have stayed, but it was a summer gig—and he decided to go back to high school.

Phylicia Rashad first met Hinton when he was a teenager. “I saw him dance,” she said. “He was strong, confident, flexible, and precise. George Faison saw him too, and he was hired for The Wiz.“

Hinton once told me he was 15 when he made his Broadway debut (he was actually 17, but close enough). The story goes that Stu Gilliam, playing the Scarecrow in the Broadway-bound tour of The Wiz in Philadelphia, got sick after Act I, though others report he was having a temper tantrum. During the intermission, the director, Geoffrey Holder, asked Hinton, then a chorus member, to take on the part for the remainder of the performance. Hinton, always confident in his dancing, said yes. With only 15 minutes to be fed lines, get fitted for the straw costume, put on makeup and a wig, Hinton went on, and, as Rashad noted, “All of a sudden, the Scarecrow took on a new meaning. The Scarecrow could dance, seemingly without a bone in his body. And who knew Hinton could sing?”

This sudden promotion was not without its challenges. Hinton sometimes knew when to speak, but on the occasions he didn’t, Stephanie Mills (as Dorothy) took a piece of straw out of his costume to let him know he was on, then “he’d improvise half the lines and jump in the air with a pirouette,” as Franzblau recalled (he later worked with Hinton as a co-producer on Evil Dead: The Musical and The Marvelous Wonderettes). Needless to say, Hinton got the role permanently and stayed in it for two years.

But he never lost devotion for his true love, ballet. Though he loved the Broadway opportunity offered by The Wiz, Rashad said, “Artistically, it was confining for him.” When he respectfully asked for a night off to appear on the dance concert stage, his request was denied. “So Hinton made the choice to be on the concert stage that night and did not show up for The Wiz. It meant the termination of his contract, but he was unfazed. He came back to Broadway in Sophisticated Ladies, Tap Dance Kid, Miss Saigon, and won three Tony awards.”

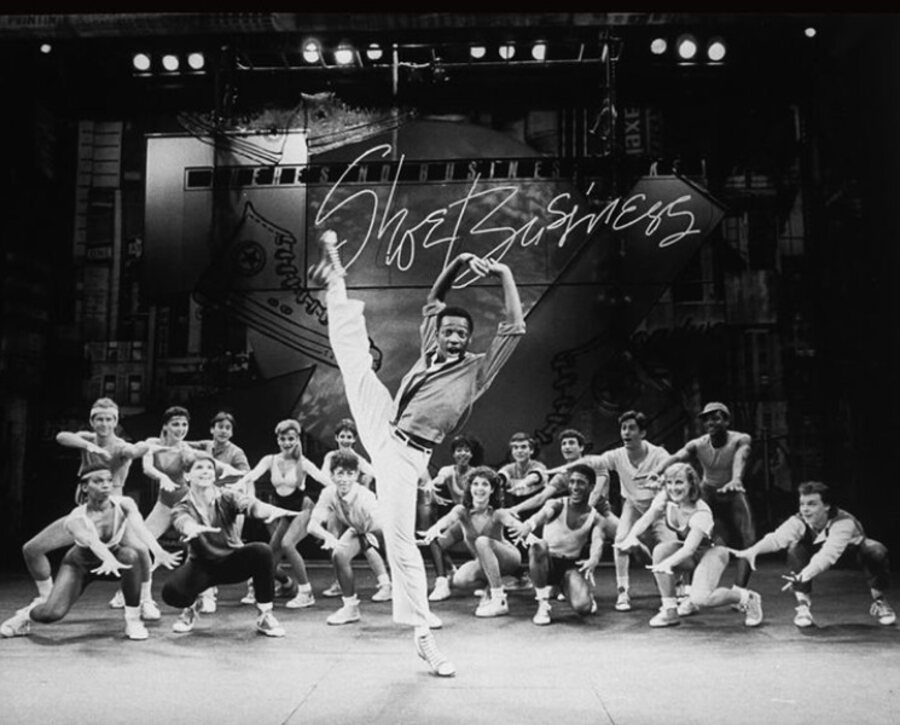

Not long after, Hinton was in the showcase On Toby Time with an all-star cast at the Universalist Church. There he met Leah Bass-Baylis, who became a lifelong colleague and friend, and who was at his side when he won his first Tony for Sophisticated Ladies. A few years later, she was the dance captain on Tap Dance Kid. Gwen Verdon helped him snow his way through the audition—he couldn’t tap, but she saw his potential. He took tap lessons before the show opened and went on to nab another Tony.

“Hinton could do literally anything with his body,” Bass-Baylis noted in our conversation. “He had the same flexibility as a woman, and was so limber he could drop to the floor in a split. But he was also strong, and when he jumped, you thought he would jump out of the room.” It wasn’t only his steps, she said. “He had this swagger and attitude and nuance—along with an uncanny musicality, which he added to the movement.” I asked her what that meant exactly, and she replied, “He could hear accents in the music that no one else could, and he’d accentuate those accents with a flip of the wrist, a tilt to the head, or a flex at the foot. He created movement phrases you just did not expect. And because of his ballet training, his placement was impeccable.”

As understudy to Savion Glover in the lead role of Tap Dance Kid, Dulé Hill (of West Wing, Psych and The Wonder Years fame) worked with Hinton on the Broadway show. When it went on tour to San Francisco in 1985, Hill took over the lead role of Willie, with Hinton as Dipsey. Hinton was Hill’s role model, he told me: “As a young performer, he was it. Hinton was the man. He could sing, kick like no other, leap in the air, act, and do everything a performing artist could imagine. And to be able to spend all that time with him—he was one of the original people who set the bar for me.” He took a breath and added thoughtfully, “We all wanted to be Uncle Dipsey. He was the North Star.”

Another long-time colleague was Kenneth Ferrone, associate director of Broadway’s SpongeBob and director of the upcoming The Wanderer, as well as Sistas. Ferrone told me, “Hinton was not only one of our true triple threats in theatre, but actually a quadruple threat. I witnessed personally his multi-faceted artistic talents, which often extended to backstage, as music and dance arranger, as well as choreographer, director, producer, and a teaching artist. He knew how to captivate an audience.”

Ferrone reminded me of the time we were filming Sistas for BET-TV at St. Paul’s, a Black church in Brooklyn. We had two performances scheduled, at 4 and 8 p.m., with both our cast of five and 100-person choir. The first show with 600 audience members was taped, but just as a backup. Then the second show started—with 800 audience members. At about 8:20, the electricity went out because we had too much load, with TV cameras, sound equipment, and lights on their system. The tech guys and Franzblau went to work, but the audience was getting restless. Franzblau pulled Hinton aside and said, “It’s your job as producer to keep the audience engaged so they don’t leave or lose their energy.” Hinton jumped on the stage and led the audience and the chorus in singing “Blood Will Never Lose Its Power,” a rousing hymn. As Ferrone recounted, “That spoke to the exact moment we were experiencing. He had the entire audience on their feet, doing one song after another.“ After 40 minutes that seemed like four hours, somebody performed a miracle and the power was back on. Everyone gave Hinton a standing ovation, and we started the show again from the top. Ferrone and I sighed across the room to one another.

Like everyone else I talked to, Dulé Hill noted the impact Hinton had. “He was always going to brighten the room,” he said, switching to present tense to recall the experience: “Whenever he enters, a big smile comes across your face and your heart gets lighter.”

His teasing was legendary. Sam Mattingly, his PR agent for years, said one of the first things she noticed about him was his wonderful sense of humor. “We sat and laughed all day,” she said. “He teased me, and I teased him.”

“Hinton loved messing with people,” said Dawnn J. Lewis (known for Tap Dance Kid, TV’s A Different World, and the film Dreamgirls). She told me a story I hadn’t heard: One day between Tap Dance Kid shows, some of the principals wanted to go grab some sushi, but Dawnn said she’d tried it and didn’t like it. She was told: You’ve gone with the wrong people, we’ll show you. They sat down and Dawnn told them she’d eat whatever they ordered, so Hinton said, “The first thing you have to do is take this green pasty stuff and put a forkful on your tongue to clean your palate. You probably didn’t do that last time, which is why you didn’t appreciate the taste of the fish.” She plunged her fork into what she later learned was wasabi and put it to her mouth—but not before two cast members grabbed it out of her hand at the last minute. “Hinton was cracking up,” she said. “He almost damaged me between shows!” Lewis laughed as she recalled the prank. She also shared the way Hinton stuck up for her when the show’s director was being too harsh with her, telling him to “stop speaking to her that way.”

Mattingly said she admired Hinton’s humility and graciousness. “We walked down the street,” she said, “and people would notice him. He was always in awe of that. Kindness—that was Hinton.” When Tap Dance Kid went on the road, Hinton wanted her to come along to San Francisco, but she had a baby. “Bring him along,” he told her. “I’ll tell everyone you’re my wife and he’s my son,” which Mattingly thought was hilarious. During the after party, she told me, “He literally did introduce me as his wife. Then he laughed.”

Even in later years, after he quit dancing because of injuries, he was always active. A few years ago, Franzblau was producing a revival of Tap Dance Kid with three Broadway stars. The day of industry reading, the actor playing Dipsey called and said he couldn’t make it, so Franzblau went to the cast and said they could cancel it—or Hinton could step into his old role. Hinton asked for an hour to relearn the part. “He went on as Dipsey, a role he hadn’t looked at for 30 years. He was unbelievable!” marveled Franzblau.

Everyone I spoke to noted how Hinton always had ideas and was working on various projects, from the Hinton Battle Dance Academy in Japan, where they had national contests like America’s Got Talent, to the Hinton Battle Danze Off competition in D.C. at the Gaylord National Resort, which comprised three days of young people working with top artists, both from within and outside the dance world.

Then there was Soul Dance Barbecue, which Denise Saunders-Thompson organized. What was it? I asked her. “Well, you know Hinton. He loved to dance and he loved to eat.” So they had a dance workshop followed by a barbecue.

He was also working on a children’s book, a memoir, and a musical based on his life, written by his colleague, Inda Craig-Galván, a playwright and TV producer-writer. Hinton told her he was beaten up every day as a kid because he was a scrawny guy who wanted to be a dancer. Because his mother realized he needed a new environment where he could flourish, she sent young Hinton and his sister to New York to live with relatives. From ages 12-15, he got a scholarship to study at the School of American Ballet under George Balanchine, and he found people who cared about him and nurtured his talent.

His longtime friend and colleague Leah Bass-Baylis was there for Hinton in later years as a source of abiding support. When he was asked to start the Hinton Battle Dance Academy in Japan, she helped write the business plan, which she shared with me. As an academic in business administration, I read that plan with great interest and found it so thorough and well-written, I could use it as an example for my students. At the end, Bass-Baylis was a true comforter. Three of those I interviewed—Lewis, Hill, and Franzblau—used the word “angel” to describe her presence and unwavering support, though Bass-Baylis told me she didn’t feel very angelic. She and Hinton had fights and arguments over the years, she said, but they were there for each other; she accompanied him to the Academy Awards, the Kennedy Center Honors, and the Tony Awards. “We congratulated one another on our accomplishments,” she told me, “And our friendship flourished because we supported each other and could be brutally honest. We could go for years and not talk and then call one another for help or just to share something.”

Also there at the end was Debbie Allen, who told me, “I saw him the night he left. I was there.” She said he whispered to her, “Bye. Love, love, love you.”

Dorothy Marcic, Ph.D., is a Columbia University professor, Fulbright Scholar, and playwright of Sistas: The Musical and Respect: The Musical. She‘s the writer of 21 bestselling books and award-winning screenplays and is co-creator of the Wondery podcast “Man-Slaughter.” With Hinton Battle and Kimberley LaMarque Orman, she has co-authored the series Tapestry of American Black Theatre for this magazine.