I met with Nick Westrate at Café Cluny in New York on a sunny September morning to discuss his four-person, stripped (all the way) down production of A Streetcar Named Desire, under the title The Streetcar Project, which is about to embark on a Los Angeles swing (it will play at an abandoned airplane hangar overlooking the L.A. River, Oct. 28-30, then in a warehouse in Venice, Nov. 1-3) before returning East for a series of pop-up performances at Yale Schwarzman Center (Nov. 13-16).

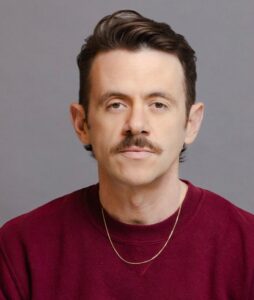

We both ordered eggs and coffee, and he encouraged me to choose fries over a dressed salad when the question of which I’d like was posed by our server. I appreciated the nudge. I’ve known Nick for nearly 20 years, having watched him in a string of unforgettable Off-Broadway performances in Unnatural Acts, The Boys in the Band, and Tribes, then in TV shows and movies like Mildred Pierce, Turn, and Ricki & the Flash.

Now, with Streetcar, Nick is a director. I saw the production at the Invisible Dog Art Center in Brooklyn late last year. The audience encircled the cast in a spare and open space. Word of mouth in the theatre community was already strong by this time, and while I was excited to see the play in a new way and support a new producing model, I was also skeptical. Could four actors with no set do justice to such a rich and complex classic? My cynicism quickly melted away as a bracing and deeply reimagined vision of Williams’s work unfolded.

As Nick prepared to head West, I was curious to know how and why the project came to be and what its future may hold. Following are excerpts from our conversation.

CHRISTOPHER SHINN: So you’re about to take Streetcar to Los Angeles. So far you’ve been mostly in the New York City area.

NICK WESTRATE: New York, Connecticut…

Tri-state.

The greater tri-state area.

Do you have a grand plan of where you want to take the show?

Lucy Owen—who created it with me—and I have this philosophy where we just keep walking through open doors. Any time we’ve done it somewhere, there’s been someone in the audience who has then offered up another space. Daniel Fish saw it at a movie theatre in Millerton, New York, and said, “Have you talked to Lucien Zayan from the Invisible Dog?” He made the introduction and Lucien was like, yeah, come do it here—where you saw it. At that show, Jennifer Newman, who curates the Schwarzman Center at Yale, said, “Hey, would you ever do this at Yale?” And I was like, “Of course, we would love to go to Yale.”

Has anybody offered a space where you’ve just thought: No, I don’t want to do the play in that space?

I don’t know if we have. We’ve definitely found that certain spaces work less well than others. We did it in the Madison Avenue Baptist Church, which is an amazing space. But different spaces have different challenges: a three-hour play with an audience in pews, not so able to turn, not so able to be mobile in their seats, all of that stuff…

I feel like I saw a photo of a performance in a clothing store in Soho.

The Rachel Comey store. A couple people who saw it there said it was almost like being inside one of Blanche’s trunks, because you just had all these clothes, and then in the center there was this huge case of jewelry.

Rewinding to you and Lucy coming up with the idea, I’m curious how much of what the show’s become you had in mind from the start. What was that initial impulse, and how different is it to what the show is now?

It was Lucy’s original impulse, and it came out of the pandemic. I, like a lot of us, wasn’t sure if I’d ever get to create art again. Lucy had always loved this play and this part, and she was like, Fuck this, I’m gonna just start working on Blanche DuBois in my fucking living room. Which happens a lot, I think—there’s that impulse that a lot of actors have, because we don’t have a lot of agency: I’m gonna do this in my living room. And then we do it one time and we work the bug out and then never do it again. But she did it a few times, and asked a couple actors to join, and then they asked me to come watch, and then it was like, Well, what if we just started working on it? And we started working on it.

We first thought we’d have a little bag of props. But as soon as you use one prop, you start feeling like it’s an acting class. I was like, you have to be able to do this on the 1 train and make it interesting. That’s kind of how the idea sprouted: out of necessity.

When you realized that the way to do it would be very simple, did you then have this vision of, we’re going to travel with it?

No, definitely not. We started working on it. A friend of ours, Ryan Hill, who is a producer and an events planner, gave us some initial seed money to rehearse it. And our friend Annie Engeman has this barn in Warwick, New York, that she uses as an event space and art space. So we went and did it in this barn. We just rehearsed it intensively. We lived there together. We cooked food, we paid everybody to be there, and we workshopped it in this barn, and then invited, like, 23 friends to see it. And one of our friends said afterwards, “Streetcar can only be in a barn—that’s the only place it can happen.” And that got us thinking: We want people to feel that way every time. We did another workshop at the Baryshnikov Arts Center and someone at Baryshnikov said, “This is the only space where you can do this play.” That’s kind of when the idea came. It started with people just giving us spaces. Then we got the rights from the estate to perform the show and did it at the Moviehouse in Millerton, New York. We wanted with each space for the audience to feel like this is the only place it can exist.

Is there a process when you get to a new space where you connect in some deep or intuitive way with the space? Or is that just sort of happening of its own accord?

I think it all ends up becoming very practical. We get a space like the Rachel Comey store, and we start looking around like, Okay, where are we going to seat people? How many exits do we have? And then that starts to dictate the rest of it. Sometimes we have a lot of time in the space, and sometimes we have as little as, like, two hours.

I feel like when I bought a ticket, there was something on the website that said 90 percent of ticket sales would go to the artists. Was that always the plan?

A lot of my advocacy has been about fair wages, and it’s just an ethic for me that is important, because I’ve spent so much of my life being underpaid as an actor. So when we started, we knew we had to pay everybody something close to a living wage. And I included the royalty to the Williams estate in that 90 percent, because that is money to the artist, the most important artist in the room. We sell the tickets in order to pay people. It is a direct-to-artists model.

Now we have new producerial challenges. Up till now, our spaces have been donated, but we’re renting space for the first time in Los Angeles. We’re flying there, we have to put the actors up. But none of the actors are being paid less than they were.

I think the producing model is really powerful, even with the changes that you’re describing. Because I think it often feels like, when you see a play at a nonprofit theatre, you are paying the theatre rather than the artists. So to see this and feel like I was directly supporting artists—psychologically I felt in a very different state as I watched the play.

It goes back to something that I’ve been wondering for a long time: What is an actor-centered model of making theatre? Traditionally, the actor is always the last person invited into the room. What is it when the actor is the first person considered? Because I think the relationship between the actor and the playwright is a physical relationship. The actors know the most about the play because they run that language through their bodies. They have to breathe and live that text.

That opens up a question. You said earlier that no nonprofit would have allowed you to come in and say, “I want to direct Streetcar.” You’ve had an incredibly illustrious career as an actor in New York. You’re a Drama Desk winner. You’re one of our best stage actors. What’s wrong with our nonprofit system that somebody like you couldn’t go to an artistic director and say, “Hey, we have a vision for Streetcar in a way that’s never been done before”?

So much of the producing model in the nonprofit theatre, especially in New York, is built around the star system. It’s built around who is a star director, who is a known quantity, and who is a star that will sell a lot of tickets. And what ends up happening is that working-class actors like myself or Lucy Owen or Mallory Portnoy or Will Rogers or Brad Koed—that’s the cast of the play, and James Russell, who will join the cast in L.A.—actors who have worked at the highest levels on and Off-Broadway, as we get older, these parts become completely unavailable. If you left to become a major star in Hollywood and come back after 20 years, then you get to be Nora in A Doll’s House.

Speaking just for myself, I’ve felt so much disappointment in the leadership of New York City nonprofit theatres—a feeling that real artists are not given the respect that they’ve earned. A lot of us, all we do is complain. So it’s incredibly inspiring to see you and your collaborators actually do something outside of that system. Many of us fantasize about it, but almost nobody does it.

It’s hard, and it takes a lot of audacity. I always have to remind the actors that what they’re about to do is audacious, because also in this production, there’s nothing for them to hide behind. They are naked and alone in front of these people for two hours and 45 minutes.

Also something that’s unique in how you’re doing this play is that you have been able to live with it and work on it for years now. Most plays, when they get done in New York City, there’s a six- to eight-week process from a first rehearsal to an opening night, then a month-long run and that’s it.

It’s an incredibly deep and profound play, fathoms deep, and we find new things about it all the time. It’s life and death. It’s about these two sisters and running away from death. And the only thing the actors have to connect to is the language and the circumstances. That’s all there is to ground them, each other and these relationships.

That really makes sense, because when I saw it, it was the first time I saw the play where it really felt like real people were talking to each other—something I have rarely felt with Williams. That opened up the play for me in a way that was astonishing. The production itself is intimate, but watching it, the play becomes about intimacy.

I haven’t thought about that word, intimacy, with it before. We are really arguing for Williams as a language playwright, like Shakespeare. The original production was so mired in the history of Method acting because of Brando, and without stuff—props, chairs, cigarettes—there is less opportunity for “Methody” behavior. There is just the text and the relationships. The story of two sisters.

How long do you see this going?

It goes as long as we have spaces to do it in.

Christopher Shinn is a playwright and screenwriter. His new play, Conscience, will be workshopped early next year with La Jolla Playhouse and the Goodman Theatre.

Support American Theatre: a just and thriving theatre ecology begins with information for all. Please join us in this mission by joining TCG, which entitles you to copies of our quarterly print magazine and helps support a long legacy of quality nonprofit arts journalism.