In autumn, California’s La Jolla Playhouse seduces, greeting visitors with a eucalyptus-lined path, amber leaves dropping at our feet in a seasonal coronation. And should our footsteps have carried us by on the evening of Nov. 22, we might have been swept up in the guitar strums and a confetti-like rain of yelps of UC San Diego’s mariachi group, La Joya del Sur, as it serenaded buzzing spectators spilling outside the theatre. The setting sun that evening caught actors, playwrights, directors, and audience members paired in impromptu dance, their confident uttering of a few lyrics sparking bursts of cultural pride, then rocking, then swaying. Despite the swirly dreamscape stirred by the music, there were no stars in sight yet—just those in the eyes of a woman I noticed beside me, kneeling on the concrete, recording the set on her iPhone as if observing an apparition of the saints of song.

This intoxicating, tequila-rushing-through-the-chest kind of warmth threaded through the eighth edition of the Latinx New Play Festival (LNPF), held Nov. 21-23 at the Playhouse. Co-produced with TuYo Theatre, and inspired by the South Coast Repertory’s now-defunct Hispanic Playwrights Project, LNPF claims a space of its own. Where East Coast initiatives like the Sol Project produce and amplify work, the Latinx Playwrights Circle builds a national network of writers, and the L.A.-based Latino Theater Company’s National Latinx Theater Initiative aims to strengthen Latinx theatre nationwide, LNPF focuses on nurturing plays in their earliest stages, offering artists access to major institutions and the visibility that comes with them.

“If I were to compare us to ecology and the stages of the plant life cycle,” said Maria Patrice Amon, TuYo Theatre’s co-artistic director and LNPF’s curator, “we function as the seedling phase, identifying new stories that expand the breadth and diversity of what represents our experience of Latinidad.”

Amon—who might have seemed a soft-spoken, wide-eyed smiler if not for the red lanyard that promised fire before she spoke—relishes watching these seeds sprout into new thematic directions as she hones the festival’s artistic vision.

“Our final selections are very intentional,” she explained. “We are constantly asking ourselves: Are we unsettling our own assumptions? Getting a full spread of regions, ages, genders? Balancing the laughers with the gut-punchers, the familiar and the surprising? We want plays that push boundaries but still resonate across a wide spectrum of audiences.”

As a Latina storyteller myself, this analysis reopened a private line of questioning I had been circling—one I realized, with some irony, that I was enacting in this very sentence, i.e., whether my identity needed naming or if it already lived in the contours of my experience.

This year’s four finalists, chosen from over 150 submissions, were Arturo Luíz Soria’s Novios, Andrew Rincón’s Tempt Me, Lori Felipe-Barkin’s Ama. Egg. Oyá., and Mario Vega’s Our Lady of the San Diego Convention Center. Unlike last year’s selections, in which family and personal history loomed large, these plays often turned to religion and spirituality to ask what we hold dear, what we want to preserve, and what we insist on claiming. At the heart of these explorations, Amon noticed, was love: filial, romantic, divine, and otherwise.

LNPF is tending these arching vines with structural shifts of its own, finding inventive ways to stretch its reach. Amon was especially excited to talk about a few of this year’s tweaks: For one, because it was (shockingly) supposed to rain in San Diego that weekend—a detail she delivered with the disbelief of someone reporting snowfall in July—the festival moved its receptions into the simulcast room. Originally meant to boost seating capacity, the space was repurposed at the last minute, taking on the intimacy of a communal living room.

Perhaps the most significant evolution was digital: the addition of a livestream service that would allow audiences to toggle among language translations on their devices.

“In past festivals, we’d wrestle with how to handle Spanish,” Amon said. “Should we translate? Project subtitles? Build translation into the scene? In the end, what we want is for artists to tell their stories in the language that fits the story best.”

I tested LNPF’s closed-caption widget during the first reading, scanning the QR code printed on a small sheet of paper. A red-velvet background appeared, white text scrolling automatically like a Star Wars opening crawl. The white-haired couple beside me didn’t move, brows nearly touching their noses, as if cracking a quantum physics equation. The couple in front of me tried the captions for a moment, then surrendered to the actors’ kinetic physicality. Their permanent, Colgate-wide smiles, even through the play’s heavier moments, made me wonder: Were they happy to be there, or there to be happy?

Watching the various ways audience members respond, you quickly understand why Amon is so particular about who fills the seats. Monolingual English speakers, La Jolla regulars, Latinx-identifying folks—she’d like her LNTP audience to encompass them all.

“The ideal audience is mixed,” she said. “I love when folks from within Latinidad show up to see themselves reflected, but it’s equally meaningful to make room for non-Latinx folks who say, ‘Your culture is beautiful, and I want to be here, to watch, to support, to share in this space.’”

The festival had its start in 2017 at San Diego Repertory Theatre, which had championed Latinx work for decades before closing abruptly in 2022. When La Jolla Playhouse offered to take it on, Amon wasn’t sure what to expect. How would their theatregoers respond? She soon found out they were comfortable with risk and experimentation, as proven by the success of the Playhouse’s DNA New Work series. Tickets for the 2023 LNPF sold out within a week.

As I stepped into the playhouse’s Rao and Padma Makineni Play Development Center, that conducive crowd composition was clear. Prince Royce’s steamy bachata blasted while folks in Michelin Man-like puffer jackets trickled in. An artistic and literary panel opened the night: Vanessa Flores Cabrera, from TuYo Theatre; Jacqueline Flores, from Latinx Theatre Commons; Becks Redman, from the Old Globe; and multi-hyphenate artist Kandace Crystal traded thoughts on the state of Latinx theatre, navigating hierarchy, and honoring mentors. Progress was visible in small but telling ways: For several of them, women of color had been their early-career bosses, and the Old Globe was piloting a Spanish version of Dr. Seuss’s ¡Cómo el Grinch robó la Navidad!

Lights dimmed for the first reading. Arturo Luíz Soria’s Novios unfolds in the failing kitchen of a gringo-owned joint, trailing a ragtag crew of cooks who survive on bravado, each one jockeying to out-macho the next under the rule of Chef Gallo. The uneasy equilibrium shatters when a new dishwasher arrives and begins an affair with Luiz, Gallo’s protégé, curdling kitchen banter into something dangerous as Gallo struggles to keep the restaurant afloat while confronting the demons that might cost her Luiz for good.

In the post-performance talkback, Soria noted that he began writing the play in 2014, drawing on years of kitchen work and the rough-edged workplace families it forged through heat and routine. He recalled seeing a play that flattened the rhythm of that world—and it stayed with him. He wanted instead to create a play in which families could see and hear themselves in Spanish, Spanglish, English, Portuguese, Patwa, etc., and simply sit back and receive it all, honoring the nuances of language. Reflecting on his own queerness in those spaces—particularly in a restaurant where the homoerotic charge was impossible to miss—he landed on the question that pulled years of notes into a narrative thread: What happens when men like these, in a kitchen like this, actually fall in love?

Woven through Matanza rituals, clinking cooking supplies, and slippery sand, Novios circles a single idea: To heal, we must first come apart. “Things break, and those are opportunities to figure out how to put the pieces back together,” said Soria. “But you can never really put them back the same. They go back differently, and you start to create a new image.”

The second day opened with the Local Project Presentation, led by the TuYo Theatre’s workshop for emerging Latinx writers Pa’Letras, who shared three readings exploring appraisal in heaven, the weight of generational patterns, and a network of empaths. The question linking them together was perhaps best voiced by a character in the second play, Only Time Will Tell: Is it possible to be happy and make one’s family happy too? Or does life demand a kind of crucifixion to prove one’s righteousness?

The second reading of the festival, Andrew Rincón’s Tempt Me, was a queer retelling of the Creation story. Light opens the world, but Lucy—the Devil—invites us to imagine a familiar garden, just slightly off-kilter. A lonely, lisping animal invents dance, while Eve frays at the edges and Adam is, well, just beautiful and oblivious. When an unexpected woman slips into paradise, Lucy leads the audience through a metatheatrical unspooling of who is allowed to be good, who is cast as evil, and who gets to rewrite the story.

In his first year at Yale School of Drama, Rincón said, he was drawn to the idea of gay demons on Earth by the faint, flickering notion of an animal crossing paths with Eve. In his second year, he attended the Langston Hughes Festival of New Work—a program that brings playwrights, directors, actors and dramaturgs together to develop new plays in front of a public audience—and his professor encouraged him to use the opportunity to fully explore the tale of this hissing creature. What emerged was Rincón’s wrestling with the way gender fluidity is often demonized, shot through with a loving irreverence toward the Evangelical Pentecostal beliefs his grandmother instilled in him.

“I love writing about gods, mortals, and magic—reimagining myths, because every story, to me, is a fairy tale,” Rincón said. “For me, the heart of the play became chosen family. As a queer person, that family is vivid and necessary. I wouldn’t have survived without them. In some cases, they matter more than blood family.”

Thus far, the post-play receptions, held in the Seuss One rehearsal space, were studies in transformation: Under white lights, festival guests hovered over fruit platters, Crumbl cookies, wine, and Topo Chicos, while Luis Miguel, Shakira, and Bad Bunny punctuated the chatter with familiar beats. Folks shifted metal chairs, bridged tables, slipping in and out of conversations, English weaving with Spanish, offering hugs and exchanging Instagram handles. By night’s end, strangers had become, if only briefly, family.

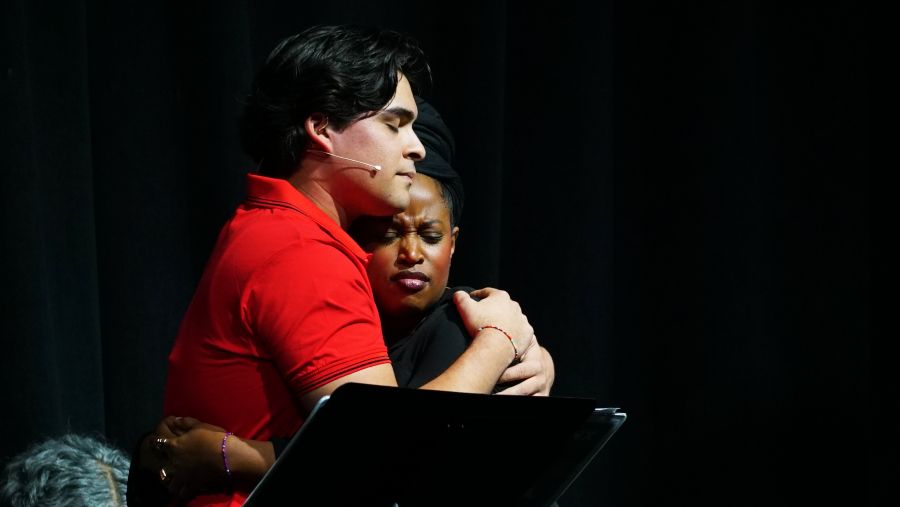

Attention then shifted to Lori Felipe-Barkin’s Ama. Egg. Oyá. The play follows Ama, a woman in Hialeah, Florida, who is resolute in her desire for a child despite repeated miscarriages—each one described in the stage directions as a shattering papaya. She is drawn to Oyá, the barren African Orisha, in whom she sees a reflection of herself. Told through Patakínes—fables through which moral advice is transmitted through the teachings of Yoruba culture—and steeped in Santería, the play carries an ilé-like rhythm as it charts the fractures of infertility and motherhood, tracing a thin line between longing and grief.

Felipe-Barkin said that Ama. Egg. Oyá. grew from a tangle of things: reaching a certain age and confronting motherhood deliberately, watching friends grapple with the same questions, and a desire to demystify aspects of Santería long subjected to othering and ostracization. She was raised in a Cuban household where her mother listened to an old santero’s radio plays of Patakínes and kept the books of Lydia Cabrera, an ethnographer and authority on Afro-Cuban traditions. It wasn’t until Felipe-Barkin traveled to Cuba for a project and saw Patakínes performed live that everything that had hovered on the periphery suddenly came into sharp focus.

“I think women who are struggling with infertility feel deeply isolated, put at a distance by everybody else,” Felipe-Barkin said. “Looking at the three principal goddesses of Santería—Yemayá, mother of all mothers; Ochún, fertile but uninterested in motherhood; and Oyá, who desperately wants a child and can’t—something about that triangle spoke to me in the midst of my own reckoning.”

The last morning of the festival arrived without rain, the sky blue for the first time all weekend. An academic panel via Zoom opened the day, moderated by Dr. Jade Power-Sotomayor of UC San Diego’s Department of Theatre and Dance. Panelists included Dr. Noe Montez, associate professor at Emory University; Dr. Jimmy A. Noriega, chair of Columbia College’s Theatre Department; and Dr. Javier Hurtado, playwright, director, and performance historian at Saint Mary’s College of California. Their conversation moved through the value of education, research as collective memory, and the deliberate work of building community. Most affecting was the Q&A, where Alma Martinez, the first Latina in Stanford’s PhD theatre program, welled up, thanking the speakers and savoring the pride of seeing them thrive.

The festival closed with Mario Vega’s Our Lady of the San Diego Convention Center, recently featured at SolFest 2025, which follows Lulu and Milli, hired as youth-care workers in a convention center that has been repurposed as a shelter for migrant girls. Shifting rules and tightening restrictions wear them down, exposing the emotional toll of the job and cracking the detached fronts they try to maintain. The play is steeped in small rituals and prayers—the rosaries, the care, the ethereal presence of women showing up for each other at the right moment—and considers how Latinx people navigate unjust immigration systems.

Vega said that the all-female story grew from his 2021 experience with Casa Familiar, a San Ysidro nonprofit supporting young migrant girls. The eldest of five, he thought caring for kids would come naturally, but he quickly realized the grief they carried was immense. After leaving the shelter to study theatre at the O’Neill National Theater Institute in Connecticut, Vega said the memory stayed with him, later shaping his MFA thesis at UCLA, where he began writing the play in his second year.

“This play is about how we take care of each other and how we fail to take care of each other,” Vega says. “It’s about what happens when we try to help and still mess up. It’s about recognizing suffering, and realizing how well I’ve been cared for, even as a grown man.”

As the festival’s final reception wound down, a toast was raised and goodbyes were shared, and Amon announced that next year the festival will partner with Latinx Theatre Commons for its next Carnaval, this time with a focus on musical theatre, and will select four new unproduced musicals by Latine creators.

“I would say we are in this lucky renaissance, an abundant flowering of the field,” Amon said. “If I had been born a little earlier, in the ’90s, I don’t think I could have built this career. Institutions weren’t ready to hear our voices onstage the way they are now.” She cited Trevor Boffone’s 50 Playwrights Project, which began with the question: Could he even find 50 Latinx playwrights to interview? The project quickly surpassed its original goal, and as of its last posts in 2020, he’d interviewed over 90 playwrights—a testament to the thriving community of Latinx theatre artists.

As I edged toward the door, I thought about how the David-and-Goliath framing of Latinx theatre vs. the American “canon” makes it easy to overlook the merit and complexity of our own work. When we stand alone, though, at a gathering like LNPF, all our multicolor dimensions appear like a burst of Prismacolor. Zooming out from Amon’s original botanical metaphor, our field moves through seed, germination, seedling, growth, reproduction, and dispersal all at once—consolidating the past with the future, maturing, dying, and being reborn through the new worlds we carry onstage. The festival’s reach in recent years has made that propagation tangible: Jayne Deely’s i never asked for a gofund me, a selection from 2024, will get a full production next year at Actor’s Express in Atlanta, while Karina Billini’s Apple Bottom, from LNPF’s 2023 lineup, has found further life as part of the Ensemble Studio Theater’s EST/Sloan First Light Festival.

These are not isolated events, but part of an ongoing process, a continual branching of who we are and the creations we sow into the wider theatre ecosystem. And while recognition from the dominant culture may come slowly, we will continue tending our garden with care, cultivating a field that blooms as authentically ours.

Miranda Purcell is an actress and journalist working across film, theatre, and communications in Puerto Rico and the U.S., with credits in award-winning projects and major news outlets. She is a 2025 TCG Rising Leader of Color and an alum of the National Critics Institute.

Support American Theatre: a just and thriving theatre ecology begins with information for all. Please join us in this mission by joining TCG, which entitles you to copies of our quarterly print magazine and helps support a long legacy of quality nonprofit arts journalism.