Know Your Own Strengths

DAVID J. DIAMOND is a New York City–based theatre consultant, career coach for theatre artists and teacher. He organizes and coordinates (with Mia Yoo) the La MaMa International Symposium for Directors and other residency programs in Spoleto, Italy, each summer.

Being an entrepreneur means taking control of your own destiny. It means understanding that you have the power and the ability to create work that will be satisfying for you. What kinds of experiences will be fulfilling to you? Once you’re clear about that, you can proceed to create the best environments around yourself to make it more likely those experiences will occur.

As an unconventional career coach for artists, I encourage my clients to forget about “careers” as such, and spend more time thinking about their art. That’s because an artist’s career is not just the pursuit of specific goals or achievements, but a way of living one’s life. The more we can unlock our thinking from the idea that “we must do things a certain way,” the better we will be able to handle the unique challenges of the artist’s life. Why is it that we are not as creative about how we pursue opportunities as we are once we get into a rehearsal room? These are our strengths: creativity, sensitivity to the world around us, the ability to reflect back to an audience a view of the universe through the lens of our personal, artistic sensibility. Let’s take advantage of those strengths.

The frustration I most often hear expressed by artists I work with is: “I’m an artist, not a business person. I don’t feel comfortable marketing myself.” Business and marketing skills can indeed be useful to obtain, but they’re not essential if you can find others who already have those skills to help you out. That requires getting over the second most challenging hurdle most artists face: asking for help.

Ask yourself this question every day: What can I create and put out into the world today that will be fulfilling and fun? Then, as my mentor Ellen Stewart would say: “Just do it!”

Venture-Capital Artists

RUBY LERNER is president and executive director of Creative Capital, an innovative arts foundation that imports best practices from the venture capital community into the cultural arena to support individual artists.

Creative Capital was established as an experiment to see if venture-capital approaches could be adapted to support individual artists’ projects. A venture capitalist builds a long-term relationship with a business, provides financial support at various stages in its life, surrounds the business with advice and other non-monetary support, builds the internal capacity of the business to thrive long-term, and has an expectation of a financial return if the business is successful. This is quite different from a more traditional, hands-off “here’s a check, send us a report” philanthropic model—and there was a lot of skepticism when we launched.

Our interpretation of these basic tenets led us to establish a structured approach to working with grantees. It includes providing modest amounts of money at strategic moments in the life of a project, coupled with extensive and multifaceted non-monetary support, like helping people build their professional networks, acquire necessary career skills and get individually tailored advice from seasoned professionals. If we think of each project an artist undertakes as its own enterprise, one can say that artists are truly serial entrepreneurs! Our goal is to provide the best shot at success for each artist’s vision—give them the skills, information and relationships to grow and sustain a thriving career; and make sure they leave us stronger than when they came in.

We have now committed $29 million to 418 projects and established a career-training program that has reached more than 5,000 artists in more than 150 communities. In 2010, Creative Capital became the subject of a Harvard Business School case study, which suggested that business entrepreneurs could learn a lot by studying our model. It gave us a lovely sense of coming full circle.

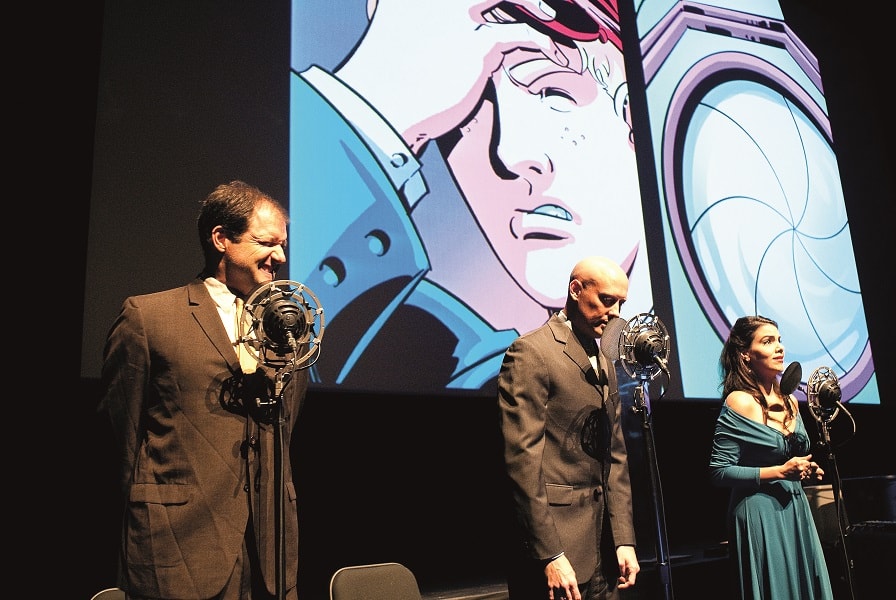

Making Your Own Rules

JASON NEULANDER is a writer, director and producer living in Austin.

All theatre artists need to look at themselves as entrepreneurs, whether they’re starting a company, working within a company or working as an individual artist. To me, being a successful entrepreneur entails setting goals, strategizing steps to reach those goals, and ultimately achieving those goals. That could mean doing something like the project I’ve been working on since 2008—writing, directing, producing and booking a multimedia show that tours the world, The Intergalactic Nemesis—or it could simply mean becoming a theatre artist who gets paid a living wage, or being the development director who meets his or her company’s grant-funding goals. Right now, my own goals are to live in the city I love, do projects I love and make a living doing those projects.

My training is really derived from my own experience. I founded a nonprofit theatre company, Salvage Vanguard Theater, right out of grad school. Intergalactic Nemesis is set up in a for-profit model, but before launching it, I never had any for-profit experience. I’ve learned what I’ve learned the hard way because I never had the opportunity to work and learn under an expert (though I’m not shy about asking questions). As a result, I’ve pretty much written my own rulebook—which has resulted in some notable successes but has also led to some colossal failures that I probably could have avoided if I knew what I was doing. I don’t think I really got a grasp on how to do what I do until I was about 40 years old—and I’m continuing to learn new things every single day. Recently, I’ve been asked to give talks about my entrepreneurial path for folks starting out on their own journeys. If you’re interested, check it out here.

Too Small to Fail

CHRISTINE EVANS is a playwright who recently joined the faculty of Georgetown University’s Department of Performing Arts.

I came to playwriting sideways, from performing in Australian indie circuses, cabarets and bands. I learned that successful work has context, built with its audiences. Musicians have skills and knowledge gained from thousands of hours of practicing, listening and playing with others. Fans and players understand that “original” music draws on a living, shared context that every performance cites and revises.

By contrast, a theatre’s “new work” slot often presents a living writer’s play as a hot new product sprung from nowhere (and destined to return there when the next hot product replaces it). Even theatres dedicated to contemporary work tend to stress “new plays” over “contemporary writers,” to such an extent that “new plays” have become a genre in themselves. But this isn’t how artists actually work. For playwrights, entrepreneurship is no longer a bold choice but a necessity.

Successful work is built over time, with collaborators, in dialogue with its times and with the art form, in pursuit of a vision: Think of August Wilson, Anton Chekhov, Caryl Churchill, Samuel Beckett. Work shorn of collaborative context and history has little chance of connecting with audiences unless it hits some button of topicality or edginess. If theatres don’t offer these critical elements, we playwrights need to take artistic leadership and reclaim them for ourselves.

My latest work is a multimedia piece called You Are Dead. You Are Here. This collaboration with director Joseph Megel and designer Jared Mezzocchi incorporates projections from Virtual Iraq, a game-based software the military uses to treat PTSD. We formed a band, then looked outside the commercial and not-for-profit theatre for developmental support. Starting with workshops and residencies at University of North Carolina–Chapel Hill and American Repertory Theater in Cambridge, Mass., where we already worked, we went on to attract interest from Georgetown University’s Davis Center, Virtual Iraq’s design team, the EST/Sloan Foundation, the Rockefeller Foundation’s Bellagio Center and the Australia Council for the Arts. It took more than three years to build the work, which will premiere in June of this year at HERE Arts Center in New York.

We came together like a band does, through a shared vision, and decided what we wanted to do; only then did we look for people and places to support our vision, the way a band finds gigs. Context, audience and our shared practice have sprung forth from there.

Training for the Real World

TRAVIS PRESTON is dean of the CalArts School of Theater in Los Angeles and artistic director of CalArts Center for New Performance.

A constant state of transition and evolution is now the norm in many spheres of artistic practice—traditional structures continue to fade away and are replaced by a dynamic and ever-shifting landscape of possibilities. In this environment of flux, I believe the artist/entrepreneur has become the dominant component for sustaining an engaged, satisfying and meaningful artistic and professional life.

Irrespective of aesthetic interests, from the most extreme and experimental to the most traditional, artists must nurture and develop individual vision together with the agency to effectively realize it. This demands that, in addition to developing the skills needed to become superior artists, they must cultivate the drive and practical expertise to carry their work to the larger world.

This makes me constantly reflect on the role of training in the performing arts. It is not enough for a theatre school to train someone to be a good artist and then show them the door at graduation. Emerging artists today must be armed with an array of skills that prepare them to generate their own professional environments. Now, more than ever, they must have the agency to immediately engage the profession when they graduate.

We are actively pursuing this conversation at the CalArts School of Theater and have dedicated ourselves to creating a training environment that nurtures and promotes student agency and self-motivation. On the curricular level, this has expressed itself in an array of courses on entrepreneurship, fundraising and producing. More important, we seek to bring students into contact with a multiplicity of relationships, communities, opportunities and professional environments while they are still in school. These span a diverse range of aesthetic landscapes, ranging from projects with Walt Disney Imagineering and the web content producer Vuguru, to collaborations with performance art collectives such as Machine Project and My Barbarian, as well as the Oregon Shakespeare Festival. We created the CalArts Center for New Performance to function as a vital bridge for our students to the profession. In addition to producing our own professional work, we also use CNP to provide infrastructure to important alumni groups in need of support—like the performance collective Poor Dog Group.

All good artists need connections and relationships to succeed, whatever their aspirations or arena of endeavor. It is the obligation of any superior school to help forge those relationships.

Asking Why Comes First

ADAM THURMAN is director of marketing and communications at the Court Theatre in Chicago. He is also the founder of Mission Paradox, an organization devoted to connecting art and audience.

Entrepreneurship is a constant process of finding ways to separate yourself from the pack. In the performing arts, “the pack” is huge. There are thousands of actors, designers and potential administrators competing for scarce spots.

If you’re one of those people, I assume you want two things. First, you want to get the spot. Second, you want to get paid top dollar for your skills. How do you make that happen when the number of viable choices reaches something close to infinity? You need to be able to do what a top entrepreneur does—you need to be able to create and define value, in this case your value as an artist or administrator.

Why should I choose you over someone else? That’s the question a good entrepreneur obsesses about. You should do the same. The alternative is being seen as “just like everyone else.” I wouldn’t call that a fate worse than death, but it’s pretty close.

In 2007 I started my freelance consulting firm, Mission Paradox. Since then I’ve invested a lot of time and energy in showing artists and arts organization how marketing can be used to create, define and express value to specific audiences. The biggest part of my training is helping clients smash through misconceptions about what marketing is and what it can accomplish. For the record, marketing isn’t about print ads, or e-mail, or social media. Those are just tools of the trade. Marketing is about building an authentic, emotional, credible connection with a select group of people. Once you have the connection, getting them to buy a ticket is the easy part.

An Entrepreneurial State of Mind

JAMES HOUGHTON is founding artistic director of New York City’s Signature Theatre Company and Richard Rodgers Director of the Drama Division of the Juilliard School.

Arts entrepreneurship is a state of mind that liberates artistic expression. An arts entrepreneur is someone who has a vision for what is possible, transformative and innovative, and then takes an active step toward giving life to that vision. Ultimately, entrepreneurship is an action that fuels everything we do, in that it reflects a fundamental belief that those actions can change the world. It is absolutely necessary if an artist and the arts are to meet the challenge of relevancy.

There is an inherent optimism in this idea—and some would say even a naïveté is required to choose to forget all the obstacles in the way of meeting any artistic moment. It is essential that we, as a community, create the safe and generous space for entrepreneurship in our work. We must encourage young and old alike to confront the endless supply of fear that gets in the way of expressing points of view and the distinctive voice that characterizes artistic accomplishment.

This is what entrepreneurs do. This is what artists do. Every time they write those words, meet that beat, draw that line, dream that place. They take an action toward a vision that is uniquely theirs; they own it, take responsibility for it, and sink or swim in it.

It is brave. It is vital. Action always is.

At the Foundation Level

MICHAEL ROYCE is executive director of New York Foundation for the Arts (NYFA).

The New York Foundation for the Arts has provided unrestricted grants to artists for 42 years. People such as David Henry Hwang, Suzan-Lori Parks, Tony Kushner, Julie Taymor and Taylor Mac received funding early in their careers to support their creative process. Brilliant artists—those rare individuals who can demand, through words and imagery, that we collectively pause and attend—communicate their ideas after having worked them through a multitude of potentialities, changing directions when the work itself calls for it. This process gives the work a power and life all its own, which, in return, makes us think about our own lives in ways we never had before. Through a structured organization of language, spoken or unspoken, these artists put themselves out there knowing they will be judged for civic value. In other words, they are entrepreneurs.

Merriam-Webster’s Online Dictionary defines an entrepreneur as “one who organizes, manages and assumes the risks of a business or enterprise.” Such people are sought out by global leaders who recognize the need for entrepreneurial application in solving problems, because they can simultaneously process complex and multiple angles of thoughts, ideas and feelings. Clearly these men and women are highly valued in society—yet the noble warriors, aka artists, who must live their lives in this way every single day in order to create meaningful work, are often dismissed. Moreover, artists often don’t recognize their own talents within an entrepreneurial framework. One can only imagine the explosion of shared understanding that could occur if they did!

Consequently, NYFA also supports artists with training opportunities in which they learn to connect internal entrepreneurial inclinations to external areas—marketing, networking, social media and budgeting—that are compatible with the creative process. For theatre professionals, the problem is often getting one’s work seen, so we teach artists how to highlight their talents based on entrepreneurial concepts. Through one-on-one mentorships, podcasting, classrooms or online courses, NYFA brings the art of “putting it together” to the art of business. It is our hope that playwrights, actors and directors who begin by browsing our website will ultimately find a path to their own self-directed destinies.

The Agent Thing: A Dialogue

ANTJE OEGEL is the founder of the NYC and Chicago-based agency AOInternational, representing American and international playwrights, directors and designers. With founder Karinne Keithley Syers, she is the co-editor of 53rd State Press.

TINA SATTER is a playwright, director and artistic director of the theatre company Half Straddle. She attended the graduate playwriting program at Brooklyn College. Her upcoming projects include Half Straddle’s ‘Seagull (Thinking of You)’ and a commission from Soho Repertory Theatre.

OEGEL: As an agent, I’m a part of many different “enterprises,” namely the individual careers of the artists I’m working with. In my mind, the artist/agent relationship is the most fruitful when it is a true partnership—when you are both working toward the same artistic goal. This partnership turns out to be different for each artist, because goals and visions vary. I’d like to believe that my partnership with you, Tina, is a good example of the most productive kind of alliance, and that I approach it in a way that somehow adds value to your work.

SATTER: Yes, working with you, Antje, is very important now to my work as a theatre artist—and to my ability to continue working. When you’re starting out, you make stuff any way you can—and with energy, luck and with the amazing help of collaborators, you get stuff out there. But at a certain point, the opportunities and stakes get bigger; you need more than just adrenaline and friends to be able to keep moving forward logistically and strategically, and to not burn out from the exhaustion of trying to understand and manage it all. That is when an agent—particularly one who knows the specifics and landscape of the particular corner of the theatre world that you are in—becomes an invaluable partner.

I see you as a theatre person who is wholly invested in me and my work. Your belief in me is a real bolster. But with that belief comes hard-line, tangible services and feedback designed specifically to make my career sustainable now and for the long-term. This includes everything from getting my work (a printed play or a live performance) in front of the right eyes; to advice on which opportunities make sense in terms of the bigger picture; to educating me on the intricacies of contracts, so I am positioned to make money off my work down the line (thinking beyond “OMG! Someone will do my show now! Who cares about the future!?”).

OEGEL: It’s also about connecting you with the right people, helping you get residencies, putting you in touch with possible producers, presenters. For your new piece Seagull (Thinking of You), for example, which will premiere in January, we are already inviting folks and making sure that we have a far outreach.

SATTER: Yes, because the real truth to this business is that while, of course, you need to hold onto your idealistic art-making side, the part that believes anything and everything is possible, you equally have to accept and understand the nuts-and-bolts side—connections, timing, contracts, and the importance of an agent who is there to navigate for you project to project, day in and day out.

Investing in Innovation

JESSYCA HOLLAND is the co-founder and executive director of C4 Atlanta, an organization that assists artists in the business of being creative.

Often when I talk to performers about entrepreneurship training, I get this response: “I don’t see how it really applies to me.” Digging deeper, I realize that performers often see themselves as having little control over their professional lives. The lens of entrepreneurship allows artists to identify strengths and capabilities that give them that control within a marketplace. Delving into an industry analysis or constructing an operational plan is new terrain for many artists.

It is important for artists to learn a business vocabulary—by breaking down the business plan into digestible pieces, arts professionals begin to see how they bring value to the arts market. This process is empowering and, to be honest, it awakens latent parts of the creative mind. Vocabulary is transformed into action.

When C4 Atlanta first offered a seminar on arts entrepreneurship, we got insistent feedback from participants that they wanted the course to be extended. We also noticed that an intimate business-training class for artists spurred collaboration among participants from a variety of disciplines and backgrounds. Our artists are eager to continue to refine, discuss and implement business strategies. In late fall of 2012, we took the logical next step in fulfilling our mission—we opened an arts entrepreneurship center in downtown Atlanta, which provides physical space for artists to build upon their creative and financial goals.

C4 Atlanta borrowed the co-working model often found in the start-up world and synthesized it for Atlanta’s arts professionals. We give artists a place to create, plan, collaborate, teach, learn and take risks. Overhead is thereby reduced and more money and energy can be spent on innovation. Resident artists and arts organizations have access to ongoing business-development training. Under one roof, we can achieve sustainability and give emerging theatre, dance and visual arts companies the resources and tools they need to build viable businesses.

Letting Students Experiment

RICHARD BLOCK is associate head and teaching professor of design in the School of Drama at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh.

In encouraging the new generation of theatre artists who we hope will move theatre forward, the School of Drama at Carnegie Mellon created an event, now in its 10th year, called “PLAYGROUND: A Festival of Student Work,” in which students are encouraged to create whatever kind of theatre they want. Drama classes are cancelled for the week in order to provide time to rehearse and otherwise prepare for a three-day marathon of theatre. There have been upwards of 50 pieces each year, none longer than 45 minutes. The work has ranged from one-person shows to fully staged new musicals—and everything in between. Dance, Noh theatre, installations and light shows have all been explored, in any and every remotely available space in and around our building. What is most important and exciting about this event is that the students have taken complete ownership, in part because it is one of the few times their work is not critiqued or graded.

While we often talk about those PLAYGROUND pieces that have had a life after the fact—and there are multiple examples, the most obvious being the PigPen Theatre Company, now achieving success and notoriety in New York City—the achievements made by the students in terms of understanding how theatre works (and how it doesn’t) is priceless. Partly because we urge them to step out of their specific areas of study, students as well as faculty discover how much more they are capable of doing than they might have assumed. This has proven to be a wonderful opportunity for our students to synthesize their classroom learning and push themselves, and many of them have used this experience as a stepping-stone into careers in areas that were totally unexpected.

Working with Intention

MICHAEL ROHD is founding artistic director of Sojourn Theatre, founding director of the Center for Performance and Civic Practice and on faculty in Northwestern University’s MFA and undergraduate theatre programs.

Lots of folks, myself included, when teaching or leading workshops, encourage artists to define success for themselves and to make choices that are not always in the context of the systems with which they are most familiar. The idea is to figure out what existing systems don’t know and don’t provide, and then forge new paths: This is entrepreneurship. The people doing the most interesting work, having the most interesting careers and making the strongest impact on audiences are often the ones who have made something new, be it an innovative performance, a one-of-a-kind organization, an original way of working, a special relationship with a collaborator or a unique working family of artists.

Working in different educational institutions around the country, I’ve learned that many conservatories at the undergrad level and non-accredited training studios treat the business of being a theatre artist as the teaching of “résumé/networking/know the industry/on-camera” skills. There are other places that have begun to focus on pedagogies for generative artists and potential ensembles—not just teaching playwriting or producing in a not-for-profit managerial model, but encouraging entrepreneurship as a skill set to stave off dependency on a precarious and rather unforgiving system. Still others (most akin to my own practice) look seriously at ways of making the artist a valuable asset in his or her community, generating relationships and projects not based solely on theatres giving you the keys to the building—but rather giving you tools and language to seek and access funding/resources not traditionally aimed at the arts.

Entrepreneurship means intentionality; it means building one’s potential to imagine one’s career and practice, rather than wholly focusing on how to prep for successful participation in show business—which is less a route to self-determination and more a route to the brass ring.