August Wilson, America’s Shakespeare, is having a “moment,” to use the words of Constanza Romero-Wilson, the playwright’s widow and chief curator of “August Wilson: The Writer’s Landscape,” a new exhibition at the August Wilson African American Cultural Center (AWAACC) in the writer’s hometown of Pittsburgh.

Wilson’s plays are among the most performed on the nation’s stages; a new Broadway revival of The Piano Lesson starring Samuel L. Jackson is slated for the fall; and Denzel Washington is two installments into the project of making film versions of Wilson’s entire 10-play American Century Cycle, chronicling 10 decades of African American life: Fences, which he directed and in which he starred, and Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, on which he served as a producer. Meanwhile, back in Pittsburgh, Wilson’s childhood home on Bedford Avenue will soon become the August Wilson House, a community arts center, with an opening slated for the summer, and the University of Pittsburgh has launched the August Wilson Archive online.

The exhibit “August Wilson: The Writer’s Landscape” offers an interactive and immersive experience mirroring the American Century Cycle plays. Thanks to several Pittsburgh-area foundations, this educational, inspirational, and emotional presentation of what it means to be human, focused on the lives of African Americans, will be free to the public in perpetuity.

The exhibition begins with “The Coffee Shop,” a recreation of the kind of mid-20th-century coffee shop in which Wilson famously spent hours writing. Projections of handwritten notes, newspaper clippings, and even a cup of coffee are on display in the booth as you first enter the space. Said Janis Burley Wilson, president and CEO of AWAAC, “It looks like August just stepped away.”

As I walked through the exhibition with Sakina Ansari, August Wilson’s daughter, she reminisced about visiting coffee shops with her dad.

“He would take me to a place that had ice cream, so I was pacified,” Ansari recalled with a laugh. “I would sit with him and watch him write on napkins, the paper menus, the placemats, anything.” Looking at the jukebox in the exhibition, Ansari remembered that when she was about 3 or 4 years old, she asked her dad for money to play “Foxy Lady” by Jimi Hendrix. “I just loved the beat.”

Like the jukebox, every element of the exhibition is layered with meaning and context. The coffee shop isn’t just the setting of the creative birth of the writer August Wilson. It also plays a pivotal role in the Civil Rights and Black Power movements of the 1960s, as black-and-white TVs in the exhibit show scenes from protests, sit-ins, and other actions against Jim Crow segregation and racial injustice.

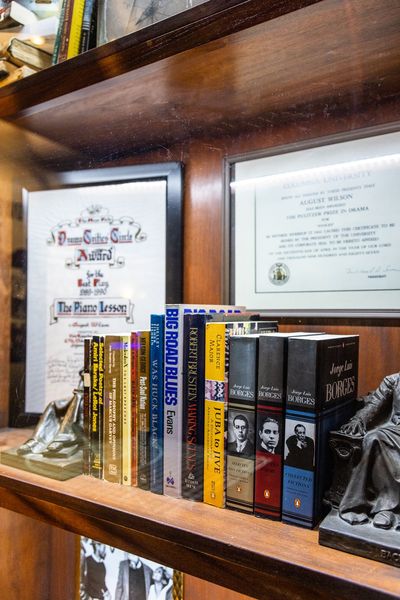

In “The Office,” the most prominent feature is a large wood table, August Wilson’s actual writing desk. On this desk several images are projected: a record album, a photo of a Negro League baseball team. By hovering your hand over the projected image you initiate the playing of a video on the desk. Covering several topics, the unifying themes are the creative and political influences that shaped Wilson’s reason for writing: “to set out with a particular purpose of raising the consciousness of the people and of politicizing the community so we could all better understand the situation that we found ourselves in in America.”

The desk was also the impetus for the entire exhibition. “A desk, roosters, and records is how this began,” Burley Wilson said, laughing. “Constanza contacted me to see if we would be interested in having August’s desk. I said yes, we will take anything. This was in 2017. We started working and thought we would finish in 2020. But with the pandemic, we had to rethink things.”

While the AWAACC was able to maintain a commitment to interaction, they lost direct touch because of COVID-19. “Luckily, in that time,” Burley Wilson continued, “technology advanced, so we could still do the things we wanted to do. For example, instead of touching something to launch media, you hover your hand over an element.”

“The Street,” the third and largest portion of “The Writer’s Landscape,” comprises installations dedicated to Wilson’s 10 American Century Cycle plays. There is a map of the Hill District and the actual streets and addresses that inspired the plays. Like the plays, this exhibit challenges us to consider the past, present, and future of African America, and America in general—the things that impact our personal and collective experience, our personal and collective hope, our personal and collective future.

Wilson’s cycle begins chronologically, with Gem of the Ocean, set in 1904. The exhibit features the distinctive voice of Phylicia Rashad, who played Aunt Ester on Broadway, pronouncing the play’s central theme: How does a Black person become a United States citizen when heretofore they were not even considered fully human?

Each of the 10 installations presents a video as well as information about the plays and their sociocultural and political contexts. The rooms also contain props, costumes, and elements from actual productions from the stage and screen. In addition to Rashad, visitors will also hear the voices of such Wilson regulars as Keith David, Ruben Santiago-Hudson, and Stephen McKinley Henderson.

Links to current events pop up throughout “The Writer’s Landscape.” Radio Golf is the story of Harmony Wilks, running to be the first Black mayor of Pittsburgh; in real life, the city inaugurated its first African American mayor just this year, Ed Gainey. In the King Hedley II installation, it’s clear that Wilson believed that death could be an inspiration for activism; direct parallels are drawn from the play to the murder of George Floyd and the global impact his death had on the Black Lives Matter movement. In the video in this area of the exhibition, one of Wilson’s monologues flows directly into the words of Al Sharpton at Floyd’s funeral: “We aren’t at the end of the fight. This is the beginning.”

Said Ansari, “When people would get my dad’s autograph it would say, ‘The struggle continues.’ It seems so relevant today. Some things haven’t changed. How prophetic my father’s work was…” she marvelled.

Burley Wilson reflected on feedback from early visitors to the exhibition. One special tour included the family of Victoria Renee Edwards, the exhibition’s designer. Despite being the nation’s youngest Black woman museum exhibit designer, Edwards died in December 2021 from complications of COVID-19. Said Burley Wilson, “People are connecting to the exhibition. They see themselves, their families—it is a personal experience.”

This was brought home when Ansari paused on our walk through the exhibition, her voice breaking a bit as she became emotional, surrounded by the words, images, props, and possessions that belonged to her father. “I am still getting life lessons from him. As I evolve and change, I hear things differently, I understand them differently.”

Said Constanza Romero-Wilson, “So much of what August wrote about still exists today.” But, even as the struggle continues, she added, “August saw that Black people are victorious.” He and his career stand as living proof.

Tereneh Idia, a freelance writer based in Pittsburgh, met August Wilson on the streets of Seattle one day. She got him to stop and talk by saying, “Hello, Mr. Wilson, I am from Pittsburgh.”