“If you find yourself dozing off during my show, don’t worry about it,” Ahamefule J. Oluo assured me, by way of a short video text half an hour before the start of their solo musical narrative show, The Things Around Us. I found it curious and ironic that my 10-show weekend—my first at the Williamstown Theatre Festival—began with an invitation to take a nap.

But, after seeing Oluo remain steadfastly chill and jovial while telling tonally disparate stories and actively constructing jazz pieces live, instrument by instrument with a loop pedal, it became clear that their words of preface weren’t an anxious hedge against a potentially disinterested audience, but rather a casual and complete acceptance of the various ways that festivalgoers might engage with their artistry. That seemed to be a common thread across all of the offerings at this year’s festival: to intentionally make space for the many ways that artists and audiences might engage with each other.

That includes the fascinating and delightful things that happen when artists and their work across disciplines are put into collision with each other by virtue of being part of the same festival experience. In addition to the short pre-show videos texted out to festivalgoers before each of the festival’s eight core productions to “help bring you into the world you’re about to enter,” I also received texts linking to a selection of articles, interviews, and other media related to each for those who wanted to “dive deeper” into any of them.

I’m a “dive deeper” kind of person, and as I read the festival’s conversation with Jacob Ashworth, the artistic director of Heartbeat Opera, whose production of Vanessa I’d be seeing that evening, I noticed that the messaging from Ashworth was quite different from what I had heard from Oluo that morning: “We want opera to be…as good as theatre. That means no one goes to sleep in our shows.”

“The W in WTF stands for whiplash,” my festivalgoing companion, Nate, joked, after I showed him that section of the article. We couldn’t help but be amused; where else could we see a clash of artistic philosophy play out between a Seattle-based solo jazz narrative artist and New York City’s premier experimental opera company?

A Season of Milestones

The 71st season of the Williamstown-based summer theatre festival—W71 for short—was full of firsts. (It ran July 17-Aug. 3.) Vanessa was the first opera in the festival’s history. The season was the first to make use of the Annex, a recently converted strip mall facility in neighboring North Adams, Massachusetts, as a performance venue, running in parallel with longtime venue partner Williams College. The Gig: After Moise and the World of Reason, another of the festival’s core productions, was the first in festival history to take place on an ice skating rink.

W71 also marked the full launch of their music festival-inspired passholder model, which promises an “an immersive, curated experience” around the festival’s eight core productions, and access to “readings, installations, third places,” and pop-up events throughout each of the festival’s three weekends. And of course, this season was the first to be helmed by playwright, performer, producer, and provocateur Jeremy O. Harris.

Harris’s full official title is creative director of the Creative Collective, an annually rotating group of “multi-disciplinary guest curators who inform the programming of the Festival,” which this year includes Kaia Gerber and Alyssa Reader, founders of Library Science; Christopher Rudd from the dance world; and Alex Stoclet from the music world. Harris is slated to lead the Creative Collective through W73.

Despite his official title and structure, it was hard not to experience the curatorial side of the festival as an auteurist project of the Slave Play playwright; Harris’s presence and influence felt inescapable, both leading up to and during the third and final weekend of performances I attended. It didn’t take long after the full season announcement for the festival to begin posting numbered “MOOD BOARD” posts that looked and felt similar to Harris’ own long-running numbered “CORONAVIRUS 🦠 MIXTAPE” posts. When the festival posted photos from their Vogue feature to instagram, the first photo in the carousel was a cropped one featuring Harris front and center. And he was ever-present in the lobby of the ‘62 Center for Theatre and Dance to greet and chat with festivalgoers in between shows.

The world premiere of Harris’s new play, Spirit of the People, was another of the festival’s core productions. One of the festival pop-up events was a mezcal (the play’s titular spirit) experience led by Harris and Justin Forstmann, the executive chef of Casita, a local Mexican eatery. Harris narrated Tennesee Williams’s words in The Gig: After Moise and the World of Reason, the ice rink production conceived, directed, and choreographed by Will Davis as a response to Williams’s similarly titled novel.

Harris’s child niece and nephew were featured as performers in Tennesee Williams’s Camino Real, another of the core productions, directed by Dustin Wills. Slave Play director Robert O’Hara joined Harris at the festival to direct Williams’s early work, Not About Nightingales. Even Harris’s rationale for the work of prolific playwright Tennesee Williams being the unifying theme of W71—“because I am queer, Southern, and a playwright who enjoys a nice dinner and a better martini”—was self-directed.

In short, If any festivalgoer entered the W71 experience not knowing who Jeremy O. Harris was and what he was about, I cannot imagine that they left that way.

Williams’s Town

Despite contemporaneous critique to the contrary, Tennessee Williams claimed in a 1975 interview that each of his plays “has a social conscience.” The two Tennesee Williams plays revived for this year’s festival lend credence to his words.

O’Hara’s production of Williams’s 1938 play, Not About Nightingales, replaced every instance of prison-set homosociality between its characters with steamy homoeroticism, and added some of its own, heightening the text’s central tension between pursuing passions of the heart vs. pursuing more material methods of freeing oneself and others from their cages. I suspect that this was a tension that a 27-year-old Williams was reckoning with himself as he wrote this piece, inspired by real-life prison brutality.

Dustin Wills’s production of Williams’s 1953 play, Camino Real, was, by design, an overwhelming and surreal phantasmagoria, wherein the majority of its 30 characters were too easily caught up in some other, more frivolous part of the chaos around them to care about the regime-backed brutality happening right in front of their eyes. Williams himself cautioned against distancing ourselves from this reality, asserting that Camino Real was “nothing more nor less than my conception of the time and world that I live in.”

Both of these revivals felt highly timely, asking how do we live—and live with ourselves—as evidence of the state’s gratuitous violence piles up at our feet and underneath our noses? The festival productions of Not About Nightingales and Camino Real presented compelling portraits of people struggling to answer this question for themselves, valiantly or otherwise.

Meanwhile, the world premiere of Harris’s Williams-inspired new play, Spirit of the People, was “not open for review,” though it was full-priced and fully staged. That’s a shame for multiple reasons, not least of which that it should have a place in this conversation, and in conversations about Williams’s work and legacy more broadly.

Ice, Baby

I can speak more freely about The Gig: After Moise and the World of Reason, the ice show conceived, directed, and choreographed by Will Davis, artistic director of Rattlestick Theater in response to Williams’s 1975 novel, one of his more confessional and explicitly homoerotic works. When I learned that the audience would be seated directly on the ice for this one, I was thrilled; finally, a chance to see Tennesee Williams with air conditioning! After the festival, I had a chance to chat with Davis about how this grand, intimate, transfixing, queer marvel of a piece came to be.

“I understand theatremaking as being about a system of gift-giving,” Davis told me, reflecting on the process of working on The Gig with five professional ice skaters and Douglas Webster, associate choreographer and founding executive and artistic director of Ice Dance International. One such gift Davis gave was the solidarity of physically showing up in the same way the performers were. “I had put on ice skates for the first time when we started this rehearsal process,” he said, and each time the performers were on the rink for “company class,” rehearsing foundational skate skills with Webster, Davis was in skates learning right alongside them. “I only fell three times!” Davis assured me.

Another gift from the process was the freedom live in the subversiveness of “these gay men getting to be gay men with each other in the rink,” especially because in the ice skating world, “it’s not at all normalized for there to be that level of sensuality or erotic tension between a larger group of these performers.”

As a queer trans man himself, Davis is constantly thinking about how to serve his community onstage. “It is always about: how am I platforming and celebrating these bodies?” he said. One fabulous example: It wasn’t until after “observing and contemplating the movement“ of Dan Donigan, known professionally as the drag queen Milk, that Davis came to understand that the “Dance of Moise” had to be a spectacular disco lip sync to “Killing Me Softly With His Song.”

“All theatre is site-specific,” Davis reminded me as I began to ask about the logistics of the piece. “And if you’re working site-specific, then your job is to specify the site.” Some sites take more work to specify than others; virtually every element of the rehearsal and production process for The Gig was impacted by the medium of ice skating and the venue, North Adams’s Peter W. Foote Vietnam Veterans Skating Rink.

In terms of casting, summer is a busy season for professional ice skaters, who often coach during the warm months. Rehearsals and performances on the rink had to be scheduled around middle school hockey practices, and some production elements had to be struck and re-installed even during the performance run. When the team realized that the ceiling of their rehearsal studio on the Williams College campus wasn’t high enough to accommodate some of the off-ice work they were doing, they rehearsed outside, which led the festival to post this outdoor skateless lift call to promote the show.

One reason that festivalgoers heard Harris narrate The Gig through individual silent disco-style headphones was that the rink’s industrial dehumidifier was extremely loud, making it hard to hear voices and music with clarity over the rink’s PA system. It was, however, important for the skaters to be able to hear each other’s movements, though they didn’t speak during the show, so they were supplied with in-ear monitors for one ear only.

Due to power limitations and the need to strike between performances, The Gig’s lighting designer, Oona Curley, had just eight lighting fixtures in total to execute their fabulously dynamic and colorful design: six intelligent light fixtures positioned on sleds right on the rink, and two spotlights positioned above the bleacher areas. “Eight lights and darkness—don’t forget darkness is here,” Davis joked.

The presence of ice skates also called for modifications to the standard production and design process. Breaks on the rink were 20 minutes instead of the standard 10, to accommodate the sheer amount of time it takes to put on and remove skates properly. Ice skating pants, including the ones Oana Botez designed for The Gig’s costumes, have zippers along the outseam or inseam so they can be changed into without having to remove the skates, and so that knee pads can be inserted or removed without hassle. (Time savings can’t have been the only reason that the stage management team and other crew who had to work on the ice opted for badass crampon shoe attachments instead of skates.)

Luckily for the festival and The Gig team, the rink was a kind and generous host, and a wonderful collaborator to Adrian White, the festival’s production director, who happens to have nearly eight years of Disney on Ice experience under her belt. Rink staff were happy to offer safety training, storage, and thought partnership on how best to execute The Gig’s production elements in their space.

Remember the part about the audience also being on the ice? That was possible only because White collaborated with rink staff to develop a way to temporarily secure moisture-resistant automotive carpet to the rink, a process that involved freezing water under parts of the carpet and onto the rink with the help of weighted spike strips. Seating could then be safely placed onto the securely frozen carpet.

It didn’t hurt that White had already been navigating municipal relationships in the process of renovating a strip mall facility into the festival’s other newly-debuted performance venue, the Annex.

Perks of the Annex

One small detail I didn’t mention in my opening anecdote about The Things Around Us and Vanessa: Both productions were running in rep with each other and with three other shows in the final weekend of the festival.

With performances covering theatre, dance, music, opera, and the amorphous space in between, the highly flexible Annex space was the breakout star of the festival for me. As I learned from festival production director Adrian White, the Annex is only in its first of three phases of renovation, with the remaining phases to be carried out in the future to expand backstage and front of house areas, install a more robust AV and lighting system, and make other improvements.

Last fall, White and the festival scoured the Berkshires for a new “found space” to rent that could support the volume of programming being planned for the upcoming season. Options were few and far between. “Unlike New York City, there’s not a huge plethora of large rooms that have air conditioning,” White said. (Besides the ice rink, of course.)

As the search continued, a new proposal emerged: The festival already owned part of a strip mall complex in neighboring North Adams, and it had been a while since the Rent-a-Center in the complex had relocated, leaving a big open space there. A neighboring unit, a former Price Chopper chain store, was already serving as festival production storage.

What if we build a black box? they wondered. What would it cost to have our own space?

It was a cost well worth the investment to have a dedicated performance venue going forward, the festival determined. The Annex was born.

White and the festival got to work immediately; White connected with Hill Engineering to conduct a feasibility study in December, leading to the development of a three-phase renovation plan. The first phase, which involved gutting the space, updating the HVAC system, and creating a functional, flexible, open room for use during W71, was completed with a blisteringly quick three-month turnaround.

The new dedicated performance space has its perks. As a former Rent-a-Center, the space already had a built-in loading dock. And the space wasn’t subject to any production limitations other than the ones they imposed on it themselves. “We can drill into the wall! We can lag into the cement floor!” White rejoiced. What’s more, the festival has a space of their own to activate during the off-season if they choose.

Perhaps the biggest perk was all the cool programming that happened in the space throughout the festival. While the seating was arranged in a three-quarter thrust arrangement the entire time, I still feel like I got to experience something new and different there each of the five times I entered the Annex in the festival’s final weekend.

Rounding out the festival’s music offerings after Oluo’s The Things Around Us were two nights of Late at the Annex, one-time-only 11 p.m. performances that were different every night through all three weekends of the festival.

On Friday, Rostam, of Vampire Weekend fame, played a set with a cello quartet. Festivalgoers that night earned bragging rights for being some of the only people in the world to hear one of Vampire Weekend’s songs “as originally intended,” with Rostam and four cellos. On Saturday, even I couldn’t help getting out of my seat to dance to Delta Rae’s powerful, witchy rock songs. The set also included a preview of some songs from The Ninth Woman, a “Southern gothic musical” the group had been developing while they were in town.

The Annex was also the venue for Many Happy Returns, Monica Bill Barnes and Robbie Saenz de Viteri’s “version of a memory play” put into context with Tennessee Williams. In the zany and jubilant dance piece, Saenz de Viteri played the voice of a character, and Barnes, along with other dancers, played her body. The emphasized separation lent itself well to slippages between what might be considered real vs. performed.

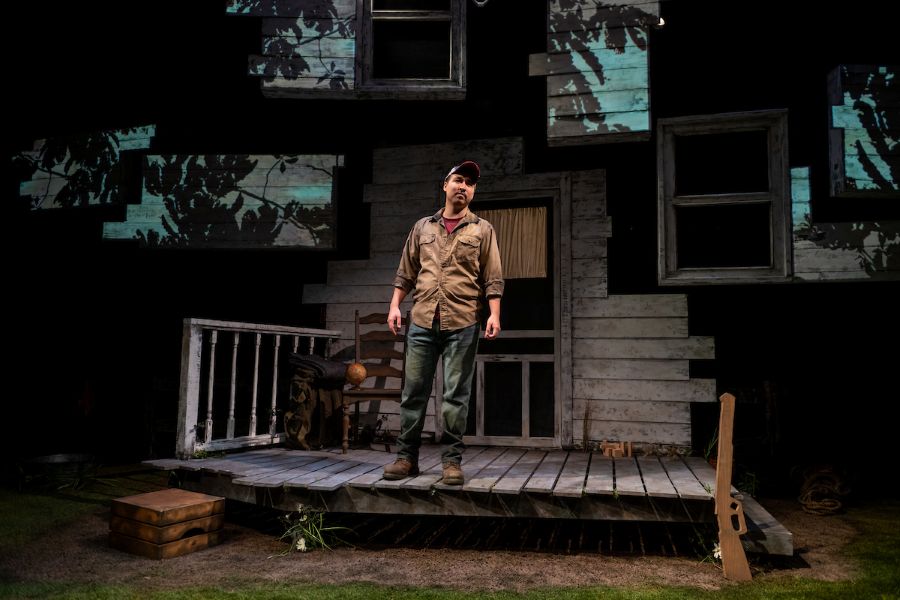

I was especially wowed by Heartbeat Opera’s revival of Vanessa, which won a Pulitzer for its music after premiering at the Met Opera in 1958 but has never been revived there. The moody, haunted, and thrilling piece, by composer Samuel Barber and librettist Gian Carlo Menotti, was adapted down to a sleek 100 minutes by Heartbeat Opera artistic director Jacob Ashworth, with direction and scenic design by R.B. Schlather, and music direction by Ashworth and Dan Schlosberg.

I’m not a big opera person, but even I couldn’t help but be awed by the formidable singers belting mere feet in front of my face, the onstage orchestra that Schlosberg pared to just seven instruments, and the delectable gothic family drama tying it all together. I wasn’t alone; my friend Nate was impressed to learn that he actually could sit through an opera without falling asleep, a big victory for Ashworth and the company.

The production was a true showcase of the potential of the Annex, being visually arresting with not much more than a nice chair, imposing silhouettes on a white wall, an impressive fog effect, and “only about a fifth as many light cues as we traditionally have,” as Ashworth and Schlosberg noted at an “artist talk” pop-up later in the weekend.

Another fun tidbit I learned from White: The construction contractor responsible for the renovation of the space also built and installed the white wall that made up Vanessa’s set. What’s more, that same contractor also temporarily modified one of the fire safety systems in the space to accommodate the production’s fog effect while keeping the space in building code. The perks of the Annex!

Putting the Festive in Festival

Running a theatre festival with Coachella-level aspirations isn’t easy or cheap, especially not while trying to repair a reputation for having a “toxic workplace culture…built on the unpaid labor of young artists”, as highlighted in a 2021 letter from then-current and former festival staff members to festival leadership.

In the years since, the festival has slowed down production activity, experienced shifts in leadership, and made adjustments to their staffing and workplace practices. All summer staff positions are now paid, including interns and apprentices. There are more explicit guardrails around job responsibilities. And there are daily and weekly hour caps for staff, along with mandatory breaks.

As the festival expands into its bold, ambitious, and risky new producing model, I had the chance to speak with both Adrian White and Adrian Hernandez, the festival’s general manager, to get a sense of what went into the operational side of W71.

By the numbers: There were more than 140 seasonal festival staff members this summer, a significant uptick from last year. Much of this growth was in the production department, a team around 70 people strong, up from around 40 last year. A fleet of 14 company vehicles, including three sprinter vans, transported festival staff and artists around to multiple performance and pop-up venues spread across Williamstown and North Adams, MA. Four staff members held the title of “driver” specifically, with many others assuming the role as part of a longer list of responsibilities, or as an offered favor. Festival staff and artists were accommodated across 18 different housing locations, most of which were dorm halls on the Williams College campus.

This year’s festival budget? $8 million (including $2 million to cover one-time transformational costs), up from $5.7 million last year.

This season was Hernandez’s sixth at the festival; he’s now serving as the general manager after having started as an intern, and serving last year as the line producer for WTF IS NEXT, a single-weekend “festival within the festival” that Hernandez called the “prototype of a prototype” for this summer’s festival experience.

“I honestly didn’t understand it,” Hernandez said of his initial reaction to the plans for the special initiative within W70, which allowed festivalgoers to purchase a single pass for over a dozen performances and events across disciplines and spaces on campus and in town, and were assigned to different tracks depending on arrival and departure time. A three-day pass was $625; a four-day pass was $850.

“It took a couple weeks to wrap my head around it, and then it happened, and we were like, oh, this is really cool.” The warm reception to WTF IS NEXT paved the way for the festival to adopt a similar model for the entirety of W71. This year, the festival sold $500 weekend passes to each of three weekends, which granted festivalgoers access to all of the eight core productions, as well as to pop-up events and other supplemental programming.

In addition to the $500 weekend pass, the festival later offered a $71 “standby pass,” which guaranteed admission to Spirit of the People and Camino Real, and allowed pass holders to join standby lines for the rest of the festival’s productions, which they could then attend at no additional cost if seats were available. Harris has long been a proponent of removing barriers to theatregoing—financial, cultural, and otherwise—and the festival’s standby passes, geared toward students and emerging theatremakers, were a brilliant addition to the festival’s model. What’s more, some standby pass holders were able to take advantage of “low-cost hostel-like housing” offered through the festival.

I saw and spoke to many first-time and younger festivalgoers who were able to experience the festival because of the standby pass system. One standby pass holder, a recent graduate, told me her housing cost $200 for the entire weekend. One group of students and recent graduates confirmed to me that they managed to make it into every single show they lined up for. The festival’s outreach to colleges, and Harris’s four and a half minute TikTok promoting the standby pass system, seem to have made a big difference, and it was wonderful to be able to experience the festival alongside so many first-timers and emerging theatremakers like myself.

Chats and Quibbles

I enjoyed the “immersive, curated experience” that the festival put together. The scheduling and variety of pop-up events ensured that I was never scrambling to find something to do with myself before, after, or between performances on my itinerary. According to Hernandez, the festival team was iterating on both the type and the timing of pop-up events even between weekends of the festival, and I can confirm that they seem to have hit a sweet spot by the time I experienced it during the third and final weekend.

Between wine tastings, artist talks, nature walks, and gallery installations, it seemed like the pop-up offerings included something for everybody, and many of the pop-ups helped promote local businesses, such as the happy hour pop-up at the lounge of the nearby Images Cinema. The festival’s relationship with the surrounding community is quite strong: More than 125 volunteers and business make up the Festival Guild, “dedicated to fostering a closer relationship between the community and the festival.” The locals and business owners I spoke to around town during my visit shared a generally rosy view of the festival.

While the festival’s productions were a major draw for me, what happened between performances was also very special. As part of the weekend pass purchase process, festivalgoers noted their arrival and departure times, and were then assigned one of six itineraries by the festival, along with everyone else with the same arrival and departure time. There was still ample time to mingle with festivalgoers, regardless of their itinerary, and ample space: In addition to the festival’s main lobby in the ’62 Center, additional seating was set up outside on the festival lawn, and inside in the festival lounge.

Over the course of the weekend, I found that Nate and I had never felt so empowered and motivated to chat with the strangers we’d seen shows with. Similarly, many folks felt emboldened to walk up, tap us on the shoulder, and chat with us, as we continued to run into each other again and again. One festivalgoer, a self-proclaimed Tennesee Williams scholar often seated next to us, was pleased to see more straightforward productions of Williams’s plays mixed in with works that had “fringe festival sensibility, but with much higher production value.”

Another pair of festivalgoers, on a different itinerary from us, were eager to exchange “tips” about the shows we hadn’t seen yet, in exchange for the same: “Tissues are mandatory for Not About Nightingales,” and, “You should grab a paper program for Camino Real if you want to keep track of all the characters.” In return, we confirmed that they should indeed dress warmly for The Gig, and that the piece was much more than “just Ice Capades.”

According to Hernandez, the new festival model was developed with the explicit intention of building “community around the art, but outside of the theatre.” I felt so much of that throughout the weekend, as I sat, ate, drank, danced, and dissected the festival’s offerings with other festivalgoers. I expect some of those connections to last; on the last day of the festival, one festivalgoer, who was seated next to Nate and I each time we were at the Annex, exchanged numbers with us and generously invited us to come stay with her in the future, so she could continue selling us on “the magic of the Berkshires,” as she had been all festival long. (Thank you for the invite, Cindy!)

If there was anything to be troubled by, it would be the imbalance in who was writing and performing in the works presented at the festival this year. Harris, in his statement on this year’s festival, describes theatre festivals more broadly as “a site to question who tells our stories and why they tell them the way they do.” Some have taken him and the festival up on this directly, observing that this season featured no plays written by women among the core productions.

It’s not an isolated issue: At an open meeting in New York City convened by the Lillys, a group that advocates for women in theatre, Williamstown Theatre Festival was named alongside Playwrights Horizons, Manhattan Theatre Club, Classic Stage Company, and Roundabout Theatre Company for announcing seasons that feature few if any women playwrights at all, or for relegating them to their smallest stages. It’s a frustrating backslide, especially under the leadership of Harris, who in 2021 threatened to pull Slave Play from L.A.’s Center Theatre Group over gender parity concerns within their season.

During my trip, I did have the pleasure of attending a staged reading of Gracie Gardner’s play, Worms, as part of the festival’s new-play reading series. While it is certainly worth highlighting Monica Bill Barnes as the co-creator and choreographer of Many Happy Returns, she regrettably had to step out of performing in the show in the final weekend to attend to a family matter.

During the modified version of the show, her male co-creator and writer, Robbie Saenz de Viteri remarked, unfortunately befitting a situation beyond his own, “Monica and I love telling women’s stories together, and it’s very weird to be doing that without her.” In this Williams-themed season, there was no shortage of tortured heroines onstage delivering lines written by men.

(The criticism world isn’t faring much better on this, to be clear; At the time of writing, I believe that Helen Shaw’s wonderful piece for the New Yorker is the only published piece of holistic critical coverage of this year’s festival yet written by a woman.)

Another pattern I noticed, even while lauding the number of queer men performing or being performed onstage throughout the festival, was that the festival casts were very twink- and twunk-forward. This year’s festival was undoubtedly a celebration of queer masculinity, but often that celebration felt concentrated on those of a certain body type.

I did raise my eyebrows at the fact that Brandon Flynn, a performer in Spirit of the People, was the only shirtless person in the festival’s Vogue photoshoot. While Harris seemingly took umbrage at Jesse Green’s coverage of the festival for the New York Times, the festival was quick to promote the “five out of five beefcake stars” Green awarded Spirit of the People. Prior to the festival opening, Harris tweeted a “pro tip”: a seat recommendation for Camino Real. As I learned during the show, performer Nicholas Alexander Chavez asked a festivalgoer in one of those seats to feel his chest during each performance.

I’m not saying this doesn’t work—delight over the festival’s “eye candy” was certainly a topic of conversation among my favorite group of standby passholders. Even so, I’d love to see more queer body diversity at the festival.

These concerns aside, I left WTF a firm believer in the potential of this new model to create exciting and meaningful cultural moments out of outings to the theatre, and I’m excited to see how they refine and develop those offerings in future seasons.

My personal hope for W72? More women writing the pages, and more bears gracing the stages. I’d be wide awake for that.

Adam Wassilchalk (he/him) is a Harlem-based arts writer, stage manager, and production manager from Austin, Texas. Learn more at https://linktr.ee/adamwassilchalk

This coverage was made possible by a travel grant from Critical Minded.

Support American Theatre: a just and thriving theatre ecology begins with information for all. Please join us in this mission by joining TCG, which entitles you to copies of our quarterly print magazine and helps support a long legacy of quality nonprofit arts journalism.