It’s a common feeling these days: I open my newsfeed and immediately feel sick to my stomach as I see yet another post about a white actor getting cast in a role written as non-white. The outpouring of comments vary from rage to cynicism, shock, and hurt. The article is shared repeatedly, the practice of whitewashing in theatre is denounced, and there is a renewed call to stand up against racism: This must not happen again. Two days later, the organization that made the casting decision puts out a statement defending their decision, citing artistic license and the lack of qualified actors to fill the role. This prompts more outrage, which results in the show being recast, going on as planned, or not going up at all.

I wait, desperately wanting us to find the words that will untether us from the comfort of our righteous indignation and compel us to mobilize decisively against the mindset that would allow for someone to think it is acceptable to cast a white actor in a role written as non-white, to use yellowface or blackface in a production. But rather than just address the symptom, whitewashing, it’s clear that we also need to confront the cause: training institutions that enforce prejudices and center whiteness.

As a teaching artist I have witnessed the negative impact that traditional training has on the people who matriculate through it. As Washington, D.C.-based playwright and educator Mark Williams told me: “True brilliance is the ability to hold mutually opposing thoughts in your head at the same time and not be broken.” I love the theatre. When I’m acting, directing, or teaching I feel completely and totally aligned with my purpose. I can actually feel the moment where I click into an energy that could sustain me indefinitely. Simultaneously I abhor the systems of oppression upheld in professional theatre, which with traditional training form concentric circles that share the same center of implicit racism and bias.

For me, action is the only way I can hold my feelings for theatre and not break. It’s time to end indifference to the pain and suffering that the training, and subsequently the industry, impose on marginalized communities. For students from marginalized groups, there is little doubt that conventional models of training fail to provide brave spaces for them to explore the vastness of their humanity. One case in point: Walter Francisco Astorga who, with seven other classmates in the spring of 2016, composed a 12-page letter to the theatre department at California State University, Stanislaus, outlining the marginalization imposed on them in the areas of “gender and sexuality, ethnicity and culture, and mental health.” Among the examples it cited were instances of brownface in university productions, and a disregard for “non-Anglo-American shows. Educational theatre should expose us to many types of theatre.” It continued with, “We should be given the opportunity to extensively explore and present theatre of all cultures, rather than in passing.”

Astorga, who has since graduated, was disappointed by the lack of response to the letter by the department’s faculty. Consequently, he says, “Most of my friends who were involved in writing the letter just completely quit theatre, which is really upsetting.”

Astorga and his fellow classmates are hardly the exception. I too, in my graduate program, faced cold indifference from faculty and administration to my numerous concerns of racism, bias, and discrimination in the interactions I had with them and with the curriculum. Vocalizing my concerns unearthed a backlash I wasn’t prepared for; I was effectively rendered a pariah and thrown out of the program, even though I’d never failed a class, in my final year. I filed an appeal outside the department with the graduate school and won the right to continue in the program, but the damage was done. I graduated numb and unsure if I wanted to continue as an actress.

Asking students to constantly disregard race, cultural context, perspective, and history in their training implies that white cultural identifiers are the default, and non-white identifiers have no inherent value and therefore should be suppressed. Examples of such oppressive erasure can be found in the lack of diversity in the most commonly taught acting methods—Hagen, Meisner, Adler, Strasberg, Chekhov, Stanislavski, and Meyerhold—where European and Euro-American theatre history are the default. There’s also the required study of white playwrights, with minimal attention given to playwrights of color, and the suppression of cultural markers held in language by teaching a “General American” dialect as the acceptable standard. This erasure privileges the experience of white students over students from marginalized groups, which I believe helps create the blind spots that allow people in positions of power to thoughtlessly discount, appropriate, or stereotype culture and other identifying markers when marginalized students go on to work in the industry.

The insidious culture of discrimination is symptomatic of a racialized system of knowledge that privileges the white narrative as superior and universal. For students of color, most of what is taught downplays or ignores their race as a factor in training. The irony is that the industry understands race as a commodity and has no shortage of roles that seek to define us solely based on race. Traditional training therefore does an inadequate job of preparing a vast majority of non-white students for the realities of the industry and the types of jobs they’ll be competing for. Actors Equity Association reported the demographics of 51,000 active members from 2015-2016 as 2.2 percent Asian American, 4.2 percent multiracial, 3.2 percent Hispanic, 9 percent African American, and 81 percent Caucasian. In contrast, the latest population data from the U.S. census states Asians are the fastest-growing population, multiracial second, and Latinos third. Has this led to sweeping changes by training programs to reflect these populations more fully?

The answer is no.

In a piece for the digital journal Ethos called “A Parting Letter to My MFA Program,” Claire Zhuang wrote that she was leaving her master’s program for acting, saying: “I see no place for myself in theatre because theatre as an institution (which I think it often forgets it is one) has not identified a way to properly engage and understand itself as a locus of domination; as a location that also perpetuates and upholds white supremacist values.”

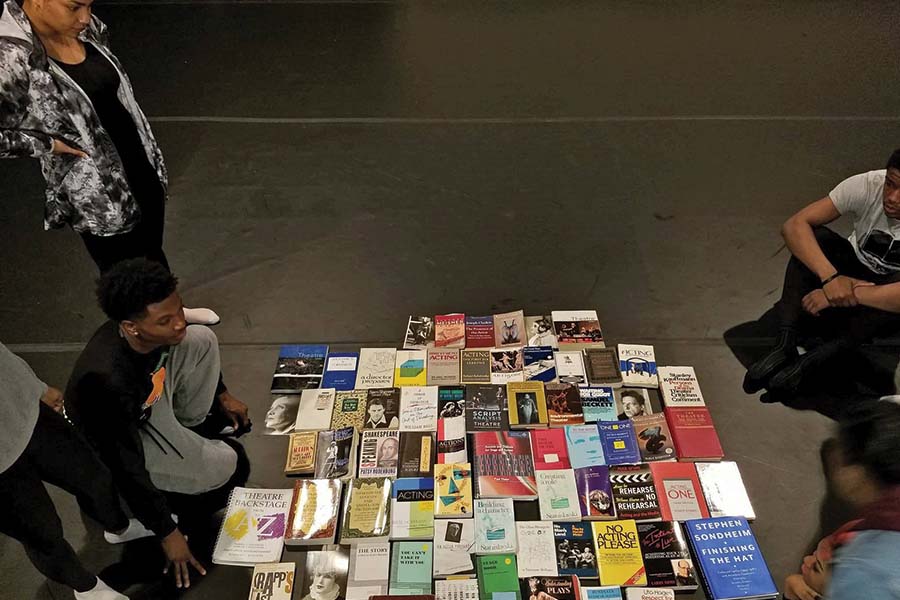

For the past few years, I have been advocating for conscientious theatre training and have helped develop a curriculum around it, along with other members of the Cross-Cultural Collaborative Committee, to combat white supremacy in the theatre training. This training takes the foundational principles of acting—listening and responding, actionable choices, voice work, presence, specificity, script analysis, relationships, movement, and vulnerability—and changes how these tenets are taught by removing the harmful erasure of non-white cultural identifiers and shifting to a communal ideology designed to minimize bias, racism, and discrimination and meet the needs of a diverse population. Through inclusivity, awareness, principles of respect, flexibility, soul-affirming techniques, and diversity of thought and rotating exposure to varied worldly methods of performance, students unearth ways in which theatre and performance are created by and for diverse groups of people in a variety of communities and settings.

Conscientious training believes that the background and knowledge each student brings must be acknowledged as relevant and pertinent to their development in theatre. The Cross-Cultural Collaborative Curriculum provides a more inclusive and impactful approach to theatre training—students are immersed in theatre and performance techniques from different cultures such as the African Diaspora, African American, Asian, Indigenous, Latinx, and Middle Eastern performance traditions. By studying the values, rituals, and practices in theatre of a selected country, students learn dialects, movement, acting, and theatre history from the perspective of that country, along with mandatory cultural competency classes, master classes, and opportunities to study abroad with artists from the featured region. In each year of study, students are exposed to a different country or U.S. region.

This kind of conscientious theatre training creates a spectrum of collaborative, responsive, imaginative, and culturally aware professionals who know the difference between cultural appreciation and appropriation precisely because they’ve been given the opportunity to study, apply, and appreciate the diverse contributions within the field of theatre.

The future sustainability of drama programs will hinge on how the current curriculum evolves to meet the multifaceted needs of a diverse U.S. population. The time has come to move past talking about systems of oppression to dismantling them by organizing and implementing conscientious training pedagogy and cross-cultural curriculums that promote transparency, equity, and ownership.

There is not a one-size-fits-all model for switching to a conscientious training program. My first advice to organizations wanting to revamp their curriculum is to seek out organizations that are bursting with resources to assist in dismantling bias, discrimination, and racism in training and the industry, such as the Black Theatre Commons, Latinx Theatre Commons, Black Theatre Network, and the National Black Theatre Festival in Winston-Salem, N.C., to name a few. For those looking to diversify acting methods, try Sherrill Luckett and Tia Shaffer’s book, Black Acting Methods: Critical Approaches; it’s a repository of knowledge on various methods used to teach acting not centered in a white Western model.

Secondly, change happens when we cultivate open communication free from retaliation. Mauricio Tafur Salgado, an actor and storyteller and co-founder of Artists Striving to End Poverty, is currently completing a master’s degree in directing from Brown University. He believes that one of the many barriers faced in addressing oppression is the restriction of information. Isolating communication to a selected few creates hierarchy, he says.

“One thing I learned when it comes to organizing communities of people, to address institutional issues, is the importance of organizing across spaces of power—organizing students who seemingly lack power, organizing faculty who have another level of power, and organizing administrators,” Salgado says. “Success is dependent on having people in every level engaging within their sphere of power.” So if your students express concerns about the program, or even write letters about it to the faculty, listen to them and work with them to address their concerns.

Imagine how different the industry would be if conscientious theatre training were incorporated into every drama program in the country. In not denouncing the privileging of whiteness in theatre training, we uphold the superiority and universality of Eurocentric knowledge, and the systems that continue to diminish, ignore, harm, and appropriate the experiences of marginalized groups. I always believed the work of theatre was to stretch beyond the comfort of bias, to work together to release the guilt that feeds apathy and chokes the ability to act outside habit. Together we can make conscientious theatre training not just a talking point, but the answer to fostering a culture of belonging that shifts the attitudes, values, and beliefs of the people who power the industry. Together we can dismantle practices that are outdated, harmful, and antithetical to the creation of brilliant theatre.

Nicole Brewer is an unapologetic idea engine committed to outing bias and discrimination in theatre curriculum, presently tithing her time, talent, and artistry as an adjunct professor at Howard University.