It’s true. Plays are about people, not things. But often, things tell me more about the human condition than characters talking to each other on stage.

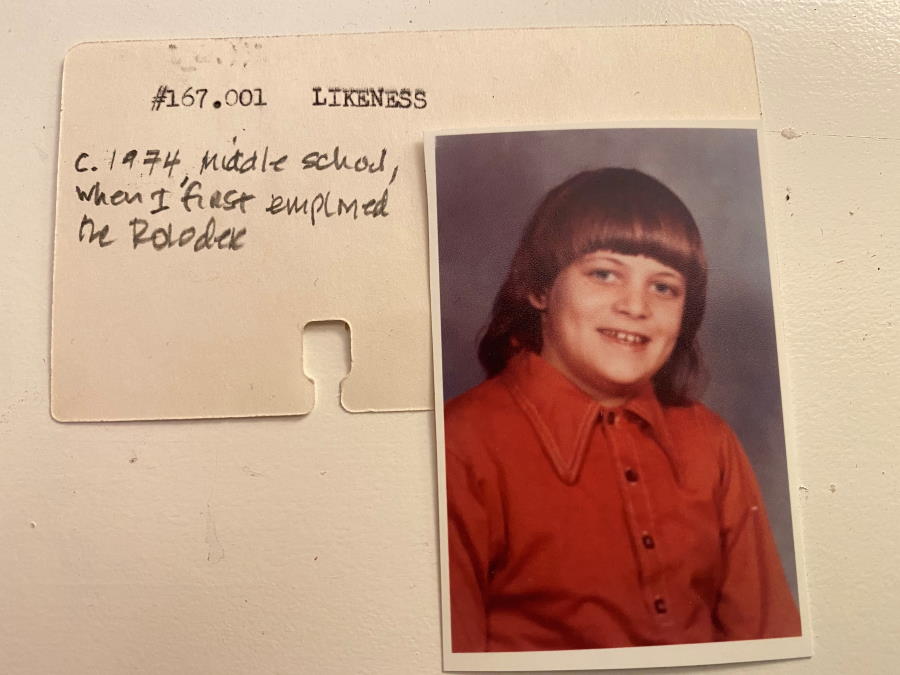

I became obsessed with objects in sixth grade. I was on the student council and in charge of our middle school lost-and-found. I cataloged the lost-and-found inventory on cards in a Rolodex file and categorized the objects into types. I’ve kept the Rolodex with me into adulthood and, over the years, added more and more nuanced categories to the collection. I have currently identified 229 classes of things, although I am sure there are many more to be discovered.

My Rolodex is a reminder of how my brain works. As a playwright living with attention deficit hyperactive disorder (ADHD) and autism spectrum disorder (ASD), I have found that objects can be an excellent organizing principle for my writing. Objects are also an alternative way for me to create work for the stage in an artistic culture otherwise dominated by dialogue, conflict, and emoting. What I’ve learned over three decades of playmaking is that my inability to create a normative theatrical experience is not a lack of craft or rewriting (as numerous literary managers and artistic directors have asserted) but rather a manifestation of my atypical neurocognitive condition.

What follows is an inventory of some of my more useful object categories. Feel free to employ these as writing prompts or as a tool for seeding actual objects into your theatrical worlds. I’ve discovered that objects are an excellent alternative method for organizing a theatrical story and can even add to the dramatic action. Even if you are writing fourth-wall farces, I hope this partial list inspires you to invent new ways of thinking about theatrical form and content.

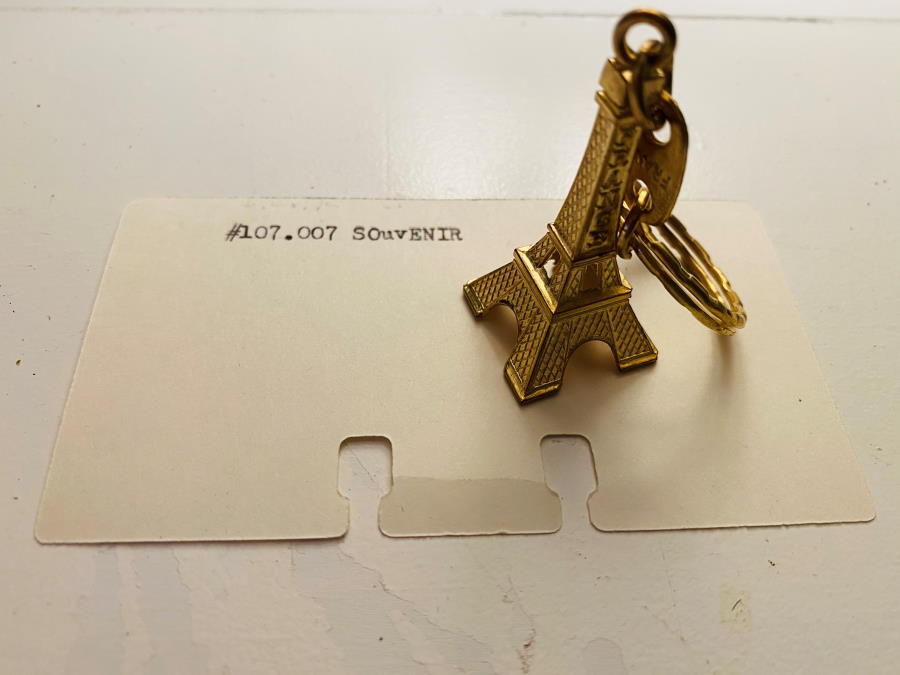

Souvenir [#107]. A souvenir is a memory of a trip, a journey taken, a time spent elsewhere. (Not all journeys end. A war souvenir may trigger post-traumatic stress in a veteran character for decades.) Souvenirs are closely related to Mementos [#43], although more tied to place than time. (A ghost character’s koala tattoo could be a souvenir of a fateful trip to Australia.) A souvenir triggers the past; it carries nostalgia and often has a loss associated with it, a memory of a “better,” more “innocent” time. Souvenirs may lose their meaning when the character who went on the trip dies. (For instance, my local Goodwill is filled with souvenirs that once had an intense emotional attachment to someone but are now just Miscellaneous Crap [#211] on a shelf.)

Souvenir [#107]. A souvenir is a memory of a trip, a journey taken, a time spent elsewhere. (Not all journeys end. A war souvenir may trigger post-traumatic stress in a veteran character for decades.) Souvenirs are closely related to Mementos [#43], although more tied to place than time. (A ghost character’s koala tattoo could be a souvenir of a fateful trip to Australia.) A souvenir triggers the past; it carries nostalgia and often has a loss associated with it, a memory of a “better,” more “innocent” time. Souvenirs may lose their meaning when the character who went on the trip dies. (For instance, my local Goodwill is filled with souvenirs that once had an intense emotional attachment to someone but are now just Miscellaneous Crap [#211] on a shelf.)

Souvenirs may also form a collection, like the commemorative plates of states where your serial killer anti-hero has buried his bodies, or the Belgian corks your contemporary Pandora character collected during her semester abroad in Brussels. Each cork holding the irretrievable memories of a night lost to blackout drinking. Postcards are typical souvenirs. (In my abandoned play Overdetermination, 15 characters find postcards from ex-lovers tucked inside books of poetry when packing personal items during breakups. Relationships are recalled in flashback, opportunities lost are revealed, and the bittersweet smell of a dusty collection of Neruda is sprayed throughout the theatre. In the final tableau, a souvenir Eiffel Tower left on a pillow has a double meaning, the ex-lovers recalling two completely different versions of the same honeymoon in Paris. [In Lou’s version, Barb flirted with a security guard in the Louvre; in Barb’s version, Lou spent most of the day in the museum bookstore searching for the perfect gift for his mother.])

Kitsch [#197] and Knickknacks [#83]. These subgenera of Miscellaneous Crap are small and seemingly worthless items that may hide deeper mysteries. Knickknacks often expose the extraordinary in the ordinary, the human in the simple. Devalued characters are often revealed in devalued things. We learn their beautiful secrets. Often a Knickknack is part of a larger, obsessive collection, like ceramic elephants or matchbooks (which also qualify as Tools [#127]).

Rubble [#73]. Rubble is a crumbling reminder of what we have lost. It’s usually the remains of a building or other constructed edifice, like a temple or school. Rubble isn’t thrown away (like Trash [#13] or Garbage [#97].) Rubble is created from entropy without human intervention. (And here I make a distinction between “actual” rubble harvested from the real world and the “theatrical property” rubble manufactured in a scene shop [see Props [#151]).

In the theatrical space, through storytelling, Rubble has the potential to transform into a Relic [#7]. Let’s say you wander the dystopian “island” (a.k.a. warehouse) of a mediocre site-specific production of The Tempest. The character of Sycorax hands you a fragment of reddish-brown brick. It’s about the size of a peach pit. You hold the fragment in your hand. While you are holding the brick fragment, Sycorax tells you that the brick is from Auschwitz and that she took it as a souvenir when she was visiting there. The brick takes on an entirely new meaning. The brick has transformed from a piece of Rubble into a Relic.

Relics may be sacred (finger bone of saint) or profane (condom wrapper from a character’s first sexual encounter). Unlike Technology [#163], which often hints at the future, a Relic carries the sting of the past. Relics frequently have historical legacy and are imbued with layers of meaning, as they are passed down from generation to generation. How a Relic was originally acquired can create a central dramatic conflict in a play. These objects are often “liberated” (i.e., stolen) from the cultures that created them—by archaeologists, soldiers, or treasure hunters—and we in the audience root for the characters who truly belong to the relics as they fight against all odds to reclaim their legacy.

Relics may also manifest as religious Icons [#79] or secular Heirlooms [#113]. Icons can allow for faith-based dramaturgy, where characters may exit their psychological prisons and enter the freedom of spiritual and revelatory space. An Heirloom has been passed down from generation to generation. Nostalgia is often associated with an Heirloom, a result of family lore told to a child by an elder. Sub-categories of Heirloom include Hand-Me-Down [#61] and Inheritance [#67]. Inheritance may be something of value or, as in my forgotten play Exploring the Incubus Archives, an entire storage unit filled with worthless junk that a character in the early stages of Alzheimer’s sorts through, hunting for fond memories of a childhood trip to the seashore.

Some objects may have magical properties, for example, the Cursed Antique [#199] or Lucky Charm [#103]. These allow a character to be motivated through spiritual, not psychological triggers, and may help break the otherwise mundane and clichéd cause-and-event cycle of American realism. A Talisman [#181] brings preternatural forces into play and may affect the dramatic action by influencing a character through belief and faith. Some Talismans take the form of Weapons [#59] (the haunted samurai sword and the like). A talisman can also be a Conversation Piece [#29]. Whatever the subgenera, the Talisman is usually misappropriated from another culture (e.g., the dream catcher hanging from the rearview mirror of the semi in The Fictional Operative, my lost stage adaptation of The Epic of Gilgamesh).

The most secular Relics are Trash [#13] and Garbage [#97]. (Please note that in my original sixth-grade scheme, Trash and Garbage are distinct sub-categories, having to do with moisture levels, organic and non-organic compositions, and whether the item was packaging or the thing that was contained inside the package. This distinction has proven far too subtle for any practical use on the American stage.) Both Trash and Garbage can be elevated to sacred status through narration. An FBI agent can pick through a suspect’s Garbage and cobble together Evidence [#53] of a crime. When a character tells a story about a piece of Trash found on the side of the road, deep human resonances may be revealed. (At intersections scattered around this city, there are discarded cardboard signs and piles of old food and other personal items abandoned by people who are homeless. In my play Leftover Future, the character of the Soccer Mom collects and assembles these piles into shrine/installations in the storage room of a diner, along with curatorial tags describing the people who once owned them.)

Tools [#131]. These are created objects specifically for human industry or work and which in their nature imply a function or action. There can be dramatic action hidden inside the Tool, which points to a character’s offstage life. A shovel covered with dirt and blood, a bucket filled with Medusa’s tears, the overheated chainsaw in the Phlogiston Foundation’s production of The Cherry Orchard—these all hint at significant offstage events. Tools can also be hybridized (e.g., a can opener with a Yellowstone Park handle is a Souvenir/Tool).

Clothing [#2]. The entire history of a character can be told in just the stains on an article of clothing. (And here I make the distinction of actual clothing and costumes {see Costumes [#109.]}) Clothing can be particularly evocative in a theatrical setting, especially when it belongs to a dead person and the audience is allowed to rummage through the pockets. They may find Trinkets [#17], Appurtenances [#89], Trappings [#101], Accessories [#137], Personal Effects [#157], and Impedimenta [#193]. Even Pocket Change [#5] can hint at a larger mystery (like when the Drifter in my play Ordering Seconds pays for coffee with change containing a Maltese lira coin). Clothing and its associated Paraphernalia [#179] can be displayed in a museum setting or possibly presented inside evidence packets duct-taped beneath the patrons’ seats. (The third act of The Fictional Operative is an exhibit of backpacks and suitcases [and their contents] that once belonged to runaways.)

Evidence [#53]. Evidence can be used to provide authenticity to a character’s story. For instance, if a character claims to have been a cheerleader in high school, a yearbook showing a photo of the character in a cheerleading squad provides Evidence of the story’s veracity. (If the character’s cheerleading sister was killed in a car crash, her bloody pompon provides Evidence of the death.) Evidence needs to survive cross-examination by the audience, especially if one or more of your characters interact with the patrons. If your purpose is to present the character as an unreliable narrator, the story will contradict Evidence the audience has seen with its own eyes. Photographs make excellent Evidence. A family photograph can heighten a domestic conflict, especially if one member of the family is left out of the photo or if the photograph provides Evidence of an infidelity. Evidence can also be falsified, providing proof of a war that never happened, or erasing a war that did happen. Evidence can be a character’s body itself; abuse can appear from cigarette burns or bruises. The irrational search for Evidence often leads a character on a crusade, for example, the quest for Evidence of a government cover-up.

Artwork [#181]. Artwork allows for a human drama that isn’t imprisoned by spoken language. (And here I make no distinction between Artwork and Crafts [#59].) The deployment of Artwork in a theatrical event is especially crucial when communicating with audience members who are most comfortable processing non-verbally. In American realism, a character is often revealed through conflict with others. Artwork allows a character to communicate with her audience using a practice that centers on beauty, invitation, and giving. Artwork can eloquently and succinctly reveal a character’s vulnerability by visually exposing the gaps between the ideal and the actual. The audience’s silent contemplation of the character’s Artwork becomes integral to the dramatic action. By sharing concrete, physical examples of her struggle to fully articulate the most essential qualities of being human, a character can provide her audience with a safe space to process their own loss, disappointment, and sense of failure. Through her Artwork, the character speaks to us, not at us or for us or regardless of us.

Artwork [#181]. Artwork allows for a human drama that isn’t imprisoned by spoken language. (And here I make no distinction between Artwork and Crafts [#59].) The deployment of Artwork in a theatrical event is especially crucial when communicating with audience members who are most comfortable processing non-verbally. In American realism, a character is often revealed through conflict with others. Artwork allows a character to communicate with her audience using a practice that centers on beauty, invitation, and giving. Artwork can eloquently and succinctly reveal a character’s vulnerability by visually exposing the gaps between the ideal and the actual. The audience’s silent contemplation of the character’s Artwork becomes integral to the dramatic action. By sharing concrete, physical examples of her struggle to fully articulate the most essential qualities of being human, a character can provide her audience with a safe space to process their own loss, disappointment, and sense of failure. Through her Artwork, the character speaks to us, not at us or for us or regardless of us.

I will occasionally receive requests from fellow playwrights to help them create a taxonomy for their own objects. Last year, the following query appeared in my mail slot from playwright Mat Smart:

Dear Sir:

I worked as a janitor at McMurdo Station in Antarctica for three months. The lost-and-found there is called Skua. Skuas are pretty much the only flying bird you encounter around MacTown. They are scavenger birds, and if you walk outside with uncovered food, they will dive-bomb you to get it. They survive on what others leave behind. Or leave out in the open. Anyway, there are so many gems in Skua, because so many people come and go. And when I was there, the jewel was an audiobook player (all one unit) that just had James Earl Jones Reads the Bible on it. All of us janos took turns with it. It broke up the monotony of cleaning toilets and mopping floors 10 hours a day, six days a week. How would you classify that audiobook player?

Answer: The audiobook player is most likely a Gadget [#71], a subspecies of Technology [#3]. Gadgets tend to be small, and they usually have a novelty quality to them (e.g., the “all in one” nature of the audio player). Theatrically, items discovered in a lost-and-found carry an intrinsic mystery—that is, we want to know who originally owned the object and why it was discarded. Scratches, labels, and other blemishes on the Gadget become clues to the item’s backstory.

The audiobook player’s taxonomy is complicated because the object may also qualify as a Recording [#149]. Recordings can be audio or visual, spoken records or text. However, to be eligible for Rolodex classification as a Thing, the Recording must also have significance as a physical object (e.g., a 45 of “Hey Jude” signed by John Lennon). A cassette tape made of your third birthday party is a dramatic trigger if it has your mother’s handwriting on the label. (In my abandoned play Indistinct Radio Chatter, an 8-track tape of Queen’s A Night at the Opera is cracked opened to reveal a desiccated queen bee, an obvious but effective metaphor that permeates the five-act family drama.) To determine whether your audiobook player meets the criteria as a Recording, you would have to submit the actual item to our basement laboratory for analysis.

More levels to the audiobook are revealed when we discover that the Recording is of the Bible. This technically qualifies the item as a Holy Text [#191]. Lastly, James Earl Jones is the narrator of the audiobook, which means that the object is also a Likeness [#167]. A Likeness is an object representing a person—real or fictional, living or dead, obscure or famous. Examples of dramaturgically effective Likenesses are 1970s Polaroids of abusive stepfathers and identity card photographs of the disappeared.

W. David Hancock (he/him) is an American playwright, best known for his plays The Race of the Ark Tattoo, Master, and The Convention of Cartography. He is a two-time Obie winner for his works with the Foundry Theatre. A collection of his plays is forthcoming from TCG Books.