This is one of three pieces about new revivals of Lorraine Hansberry’s seldom-produced second play. You can check out the other two here.

The woman who wrote A Raisin in the Sun believed her plays could change hearts and minds. But after widespread misreading of that 1959 masterpiece, though, Lorraine Hansberry was less sure about that.

“I hardly think you’d find many theatregoers willing to pay a $9.90 top to come to the theatre to be indicted,” playwright Bill Branch wrote her, “as I rather think you bore in mind yourself when writing Raisin.”

Echoing that backhanded compliment, in 1961 LeRoi Jones (later Amiri Baraka) wrote to her: “The position you have made for yourself (or which the society has marked for you) is significant. Your writing comes out of and speaks for the American middle class…The critics were joyous about Raisin for exactly that reason.”

How was Hansberry supposed to reply to this dismissiveness? To Branch she wrote, “I was a little stunned…to discover that you feel, implicitly, that I somehow contrived to write in Raisin a work which dutifully sidestepped Negro freedom because of one eye on the box office.”

This kind of response only deepened Hansberry’s inherent ambivalence about theatre. She felt drawn to activism, while her convoluted personal life alternately thrilled and depressed her. Still, she remained prolific, almost in spite of herself. As the playwright Jane Wagner (The Search for Signs of Intelligent Life in the Universe), who dated Hansberry in 1962, put it, “I loved that part of her wanted to save the world and didn’t think her plays were going to do it. She was trying to find the truth, just how good of a writer she was. She was very subjective after the success. She went inside herself.”

Hansberry finished a TV movie about slavery and started work on a sort of opera about Toussaint Louverture, adaptations of two novels, and two original novels. She nearly finished just two more plays, The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window, which was staged in her lifetime, and Les Blancs, which has been mounted in various versions since her death. Both are fascinating, especially on repeated viewings and in historical context. This month U.S. audiences will get two major revivals of Sign: In a Seattle production by the Williams Project and the Intiman Theatre, and in a staging at Brooklyn Academy of Music starring Oscar Isaac and Rachel Brosnahan.

It’s a reevaluation that’s long overdue for a play that didn’t really get a fair shake the first time around.

“Sign carried the weight of her first success,” said UC Berkeley theatre professor and Hansberry biographer Margaret Wilkerson. “While A Raisin in the Sun was very successful—it was, after all, a play about Black people by a Black woman—it was audacious of her to write a play about ‘white people.’ Writing a successful play about white people would make her ‘universal,’ and that was reserved for white people.”

“All of her plays depict the effort to stand with someone else,” said literary critic Michael Anderson, who has written extensively about Hansberry. “Such a conclusion is uplifting in A Raisin in the Sun, sobering in The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window. Its collection of broken souls illustrates the various ways we reject one another, and reckons the costs of such denial— costs so overwhelming that reconciliation can only be tentative.”

Rather than resolve ambivalence, the character Sidney Brustein invites it. Passionate, arrogant, hilarious, scattered, hostile, affectionate, and inconsistent, Brustein can be loving or vicious, open or a smug know-it-all. He is intermittently effective. He picks fights and gets distracted.

“I joke that he is the Jewish Hamlet,” says Anne Kauffman, who’s directing the BAM production. “He has that depth of despair, but he’s also one of the funniest guys around.”

Most importantly, Brustein never stops to think or to listen. “If you stop moving, you have to look in the mirror, and if you look in the mirror, who’s to say what you’re going to see?” said Chris Stack, who played Sidney in Kauffman’s 2016 Chicago revival. “Even though Sidney is incredibly magnetic and charming,” said Stack, “he’s really destructive.”

You may know a man whose stubborn inability to change led to multiple disasters, despite being a fine person in so many other ways. Many were men of World War II vintage who felt incredulous when, in the late 1960s, people grew unrecognizable to them. For anyone familiar with a certain music in the voices of uncles or grandfathers, Sidney is like meeting that guy as a younger man.

Hansberry began the play in 1960, when political corruption ran rampant in her immediate environment, as did the impulse for reform, even revolution.

“I lived around Little Italy,” recalled longtime Voice film critic J. Hoberman. “My Assemblyman was Louis de Salvio. I got a call asking me who I was going to vote for. Louis de Salvio? I said, ‘He’s a hack.’ When I went to vote, my page in the voter book was gone.”

In 1960, community members opened the first drug treatment program at the Judson Church, and in 1961, neophyte Village Voice editors helped defeat political boss Carmine de Sapio. This hopeful spirit dominated the early drafts of the play and its initially quite comic ensemble. It comprises Sidney Brustein, the former owner-manager of a folk spot called Walden Pond, who has, unbeknownst to his wife, Iris, also taken on a small community newspaper, The Village Crier. Sidney and Iris’s upstairs neighbor is (a caricature of) an absurdist playwright who achieves mainstream success. Their progressive friend, Wally O’Hara, is running to unseat the machine city councilman. Sidney’s friend Alton, a Black ex-Communist now working in a bookstore, persuades Sidney to endorse Wally. Alton is in love with Iris’s sister Gloria, not knowing that she is a call girl.

As Hansberry continued work on the play, internal divisions split the Village reform movement, and Kennedy was assassinated. Later drafts are accordingly darker: Wally turns out to be a covert machine operative, Iris is seduced by another man and the career he offers her, Alton learns of Gloria’s job and rejects her, she in turn commits suicide. Sidney must absorb all these blows, plus the blow to his self-regard from realizing that he is not omniscient.

Hansberry also drew upon personal episodes, as detailed in the handwritten draft of a preface found at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. Literary critic Anderson added that she engaged deeply with Ibsen, especially The Wild Duck, while writing Brustein. “Hansberry’s deep-rooted existential terror made her an artist as well as an activist,” said Anderson. “She understood that loneliness, isolation, and the need for intimacy is not limited by what side you’re on.”

‘‘The play was the edge of the end of something big and the beginning of something big,” the play’s first director, Carmen Capalbo, told Anderson in 1999. “With the Kennedy assassination and the continuing Civil Rights movement, there was a sense of public trauma. But ‘the Sixties’ as we know them hadn’t happened yet. In its time, the play had something to do with the death of idealism.”

Sidney “addresses the attitudes of white liberals and ‘intellectuals’ disengaging from politics,” said Wilkerson, “while illuminating the power of the individual to make meaningful change in the context of a dynamic world.”

Anderson feels that a commitment to activism, and to using art for social justice, frustrated the artist in Hansberry. “Hansberry felt guilty writing because she was not being an activist, which is the ostensible theme of Sidney,” he added. “A key to Hansberry is ambivalence, in so many ways.” Anderson discerns a “shadow side”—psychic currents within the writer’s mind that “she was unwilling to accept,” which nonetheless show up in her plays. Her husband and producer, Robert Nemiroff, “called her ‘a being uncommonly possessed of fear,’” says Anderson. “If there’s a figure in the carpet, that’s it.”

Nemiroff, ever Hansberry’s champion, was a key reason the play got produced at all.

“It was very important to Nemiroff to do The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window,” said Wilkerson. “He wanted to show that A Raisin in the Sun was not an ‘accident,’ and to demonstrate that Lorraine was a great playwright who could write convincingly about the human condition—meaning that she was not only confined to writing about Black people.”

Hal Prince even briefly joined as co-producer/director, but thought Brustein had too many subplots trying to say too much. A colleague wrote to him that Hansberry “has thought of everything except incest.” Revisions Prince requested did not happen, and he regretfully withdrew.

When Capalbo joined as director, the play still needed work, even as rehearsals began. “When she gets into a scene between two people instead of ideas, it still holds up,” Capalbo told Anderson, “but it tended to be more verbose than it had to be.” Hansberry responded enthusiastically to Capalbo’s “pointed questions,” telling him, “Thank God somebody really read the play.” But as her cancer worsened, she wasn’t able to make the changes he requested.

And there were casting problems. Most actors ‘‘didn’t bring a certain kind of music’’ to the role of Sidney, said Capalbo. Early casting wish lists proposed John Cassavetes, Walter Matthau, and Dick Shawn for the title role. Capalbo favored comedian Mort Sahl, who turned out to be a disaster. A non-actor more accustomed to improvising, Sahl couldn’t learn his lines, ran off to California, and digressed into tangents during rehearsals. After Nemiroff fired Sahl, Sahl asked Paul Newman to represent him in Actors’ Equity hearings over damages. (Newman refused, telling Sahl he lacked discipline and that “all you think about is broads.”) Sahl later claimed that as his anxiety mounted, co-producer Burt d’Lugoff, a physician, had prescribed pharmaceuticals to help him focus and sleep.

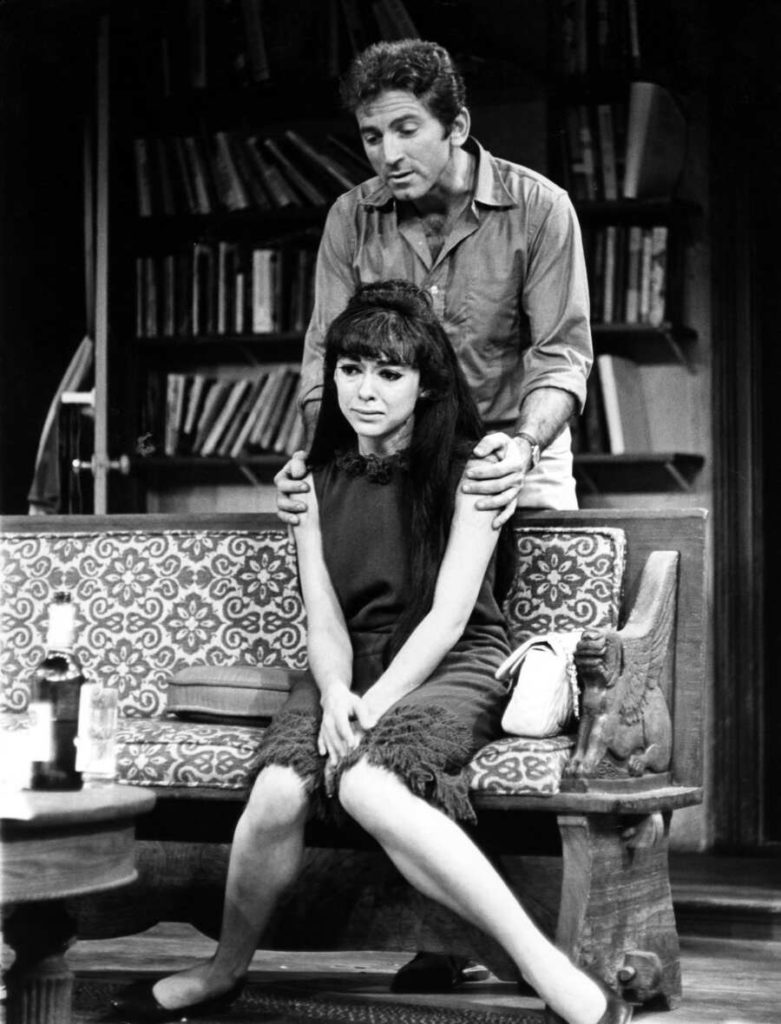

Gabriel Dell, a former Dead End Kid, replaced Sahl eight days before opening night. His son Gabe has a photo of the actor taken during the production; he stands at a craftsman table working on a collage. The collage includes a joint of marijuana, with the words, “In case of panic, pull tape and smoke.” On opening night, Dell apologized to the audience for remaining on book. His co-star, Rita Moreno, would non-verbally direct him to various onstage bookcases where his speeches were surreptitiously posted.

The doomed production was kept alive for 101 performances by the efforts of Nemiroff and famous friends like Anne Bancroft and Mel Brooks. Nemiroff would hold the audience for curtain speeches. “My wife is sick, keep this play alive!” Capalbo remembered him saying at one point. Douglas Turner Ward, a friend of Hansberry’s, felt embarrassed by the mawkish display. Capalbo was also appalled; he told Nemiroff, “You’re exploiting her illness; you’ve turned it into a circus.”

Reviews of the original production ranged from mixed to negative, and it closed on Jan. 10; Hansberry died two days later. Her will named Nemiroff literary executor and trustee but not beneficiary; instead he was charged with keeping her legacy alive and distributing her inheritance to her family, her girlfriend Dorothy Secules, and movement organizations. Nemiroff took producing and promoting seriously; he bought her literary rights and properties from her estate for $40,000, which would be about $300,000 now. A sharp trader and savvy operator, he stands out as one of the most devoted executors in literary history. Between 1965 and 1968, he adapted her letters, plays, and diaries into a collection titled To Be Young, Gifted, and Black and produced a second Broadway staging of The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window in 1972, though to similar indifference.

Sign has been only sporadically revisited since. The first major revival of recent years was at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival in 2014.

“Hansberry was our Shakespeare of that time,” said OSF dramaturg Lue Douthit. “It takes a lot to be moved all the time or committed all the time. But it requires not just the loner. It actually requires society for that to happen, and to stay committed. Hansberry was able to deliver to me a vehicle by which I get to do that exploration.”

It’s a play whose engine will run in your mind long after you get home from riding along with Sidney. After that, the car is yours to drive.

Elise Harris (she/her) has written for The New York Times, The Nation, and the literary journal Harp & Altar. An earlier article on Lorraine Hansberry can be found here.