Karen Olivo (she/they) has walked away from Broadway before. In 2013, after winning a Tony for their role in a revival of West Side Story, they uprooted their career and moved to Madison, Wisc., to teach theatre and raise kids with their husband, sound designer Jim Uphoff. Olivo has since returned occasionally to the stage, including in a 2018 staging of Fun Home at Madison’s Forward Theater. And their starring role in the 2019 Broadway hit Moulin Rouge! seemed like a welcome Main Stem homecoming for this powerhouse actor/singer/dancer, who first made a splash in 2008’s In the Heights.

This past week Olivo walked away again, with a 5-minute Instagram video posted on April 14 explaining why they wouldn’t be returning to their Moulin Rouge! role when the show returns, presumably in the fall. This time their exit left a mark: Deploring the industry’s silence not only about a devastating recent report about workplace abuses by producer Scott Rudin but about long-standing inequities built into Broadway’s business model, Olivo said they were using their leverage and profile to send a message to a regressive field. “I want a theatre industry that matches my integrity,” they concluded.

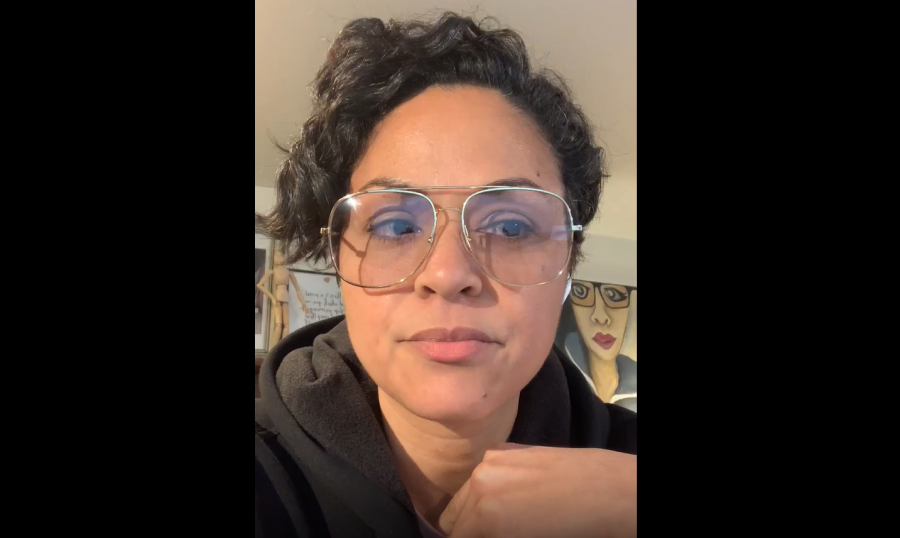

I spoke to Olivo yesterday from their home studio in Madison about the field they’re turning their back on and the field they hope to help build instead.

ROB WEINERT-KENDT: First, I have to say, brava for speaking out. Obviously your video speaks for itself, but I appreciate you taking time to talk about it some more. Though I know that it wasn’t just about you—it was a bigger statement than that—I wanted to start by giving you space to talk about your own experiences with abuse or harassment, and to ask you, if you’re comfortable talking about it, whether they occurred in the context of the industry.

KAREN OLIVO: I’m a person of color, so yes, obviously—whether it be microaggressions or you name it. I think the component of the question, which you’re being very gentle about, which I appreciate, is that I am a survivor of rape and also domestic abuse. So it’s a different framework when you come in contact with other survivors.

This business is built on a foundation of oppression, much like most of our world is. And this job specifically preys on the dreams of young people: the creation of art, something that is, in my estimation, one of the purest things. And we start conditioning children very, very young, we start grooming them for the levels of abuse—we put them through rigorous training to teach them to stop listening to their bodies, to stop listening to their hearts. And we make it competitive by giving them awards, so the scarcity model is in place. The things about art—the humanity and the grace, the divinity of it—are all stripped away by the time kids are looking at going to a predominantly white institution to get a musical theatre degree. And then what we do there is we train them harder, and we tell them, “If you go to the right school, you’ll be branded with the right brand, and you will walk through the doors, the pearly gates of Broadway, and everything will be yours—and you will get more abuse.” Because it is a structure that doesn’t believe in the art anymore. It believes in profit.

So as an educator, I feel like I have a responsibility. The moment I go back to the show, I endorse an industry that shows they don’t care about the people who are being harmed, and I do my students a disservice. I endorse something that will hurt them. And if you have a platform, if you were granted a platform—and I’ve been granted mine, truthfully, by a proximity to whiteness, conforming and being a token in rooms—the least I could do is be straight with these kids.

I know that some folks who saw your statement or the headlines about it immediately wondered, “Wait, is Scott Rudin a producer on Moulin Rouge!?” Obviously he’s not! And even though the producers of Moulin Rouge! released a statement of support and gratitude to you, the next thing I and some others wondered: Was something hinky going on with that production? Or is your point about the industry larger than any one producer or show?

I mean, look, the show is problematic because it’s all under the same structure, right? We worked too hard. I built a show that is oppressive to my physical form. I did horrible things to my body. And once you see that and you know it, you’re like: Why am I doing that? But it’s much bigger than that. I have a high-paying job waiting for me; they need me in that sense, and I can recognize that me going back and endorsing that and making money on that is the antithesis of what we need in this moment. I need to be able to step away and to be able to look at myself in the mirror.

Obviously, as you said above, your message is partly for your students, to set an example by not endorsing an industry you think is harmful. But your message is also for your colleagues on Broadway. You didn’t spell it out, but clearly you’re not the only one with a platform who could make a difference. Is part of your message intended to be heard by the likes of, say, Hugh Jackman and Sutton Foster, the stars of Rudin’s The Music Man, to say to them, “Hey, step up”?

Oh, absolutely. I’m making an assumption here, but I think that I’m not swinging too wide when I say I don’t think that Hugh Jackman is going to be out on the street if he doesn’t do Music Man. I’m just gonna make that assumption. And when he goes and makes Scott Rudin a lot of money, he endorses that behavior, and he also sends a message to all of the other predators out there: This will be condoned, this will be allowed.

Not everyone has a platform like you, though, and one critique I’ve seen since your video came out is: The onus for change shouldn’t be placed on actors and other theatre workers who depend for their health insurance on having a job; it should be on the theatre owners and producers and general managers.

Yeah, let me break it down. They want what I have, right? I am the content creator, and I have not been beaten down so much in this business that I do not understand my worth. That’s not being me being arrogant. It’s me knowing my craft. I know that the industry needs what I have, and only I have, so by withholding it—you know, it costs me. When I take of my own life force and my mental well-being, and I ask my body to do things, I want to make sure that it’s with the right people and it’s for the right reasons. Right now, this Broadway model has shown that there’s lots of theoretical change, but when pushed, it is just theoretical. I will not give everything I have to an industry that hasn’t done the work.

And I’m saying this about those of us who actually have a platform. It never dawned on me that people would assume I meant that anyone who needed a job couldn’t go back to work. That’s a choice I make for myself; you make that for yourself. But when people that I know who have a platform, white women and men who have platforms and remain quiet, when they reach out to me and say, “Thank you so much,” I almost want to say, “You do realize that I am once again doing your work for you.” Right?

But you don’t say that.

Well, no. What am I gonna do? That’s the other thing. I’m at the point where, after a year of listening and learning, if I have to explain to you right now what’s happening—who has the time for that?

Another thought I had in response to your video was, why not reform Broadway from within—stay in your show and model a different path that way?

Because I work within an oppressive system, right? Because I understand how it works. It’s a business model that puts me at the very, very bottom, regardless of whether or not I’m a headliner. Why? Why am I knowingly putting myself in that situation again? Look, I go back to Moulin Rouge!, and all of the initiatives that Moulin Rouge! has said that they’re going to do and Broadway on the whole says that they’re going to do, and I am in a position of leading a company, the company looks to you, they follow your lead—yet again, another person of color has to hold the weight of whether or not my company will act correctly. I have to be the accountability measure and do a Broadway show.

That’s a lot.

Right? It’s crazy. And I don’t believe that it was working in my best interest.

You said, “I want a theatre industry that matches my integrity.” What does your vision of a better theatre industry look like?

I actually spoke with seniors today, and we were talking about what the future is. In 20 years, we move out of New York—we’re not there anymore. That’s a real estate game. Truly, the gatekeepers of Broadway are three entities, and they’re real estate moguls. You know, gentrification has a lot to do with the Broadway model; we’ve pushed people out of the places they live so we can have more things for Broadway and for the tourists that we fly in. Once we divest from that, we could start looking at models in which cities have their own theatre, and they create an ecosystem around that theatre or a cluster of theatres. It could be all over the United States. And people wouldn’t have to move so far away. I feel like it would be more inclusive. We’d have better stories, we’d be talking about so many different things.

Well, you’re preaching to the choir now, because American Theatre is the magazine for the U.S. nonprofit theatre field, and that’s kind of the dream of the regional theatre movement you just described. It has fallen short in a lot of ways by following a similar, Broadway-focused industrial model, but I still think there are plenty of hopeful examples in it for a better way forward, of theatres that are real community centers as opposed to profit centers. Have you seen some of that in Madison?

Forward Theater has tried to do that. But Wisconsin is a problematic state. There’s a lack of tolerance and a lot of racism here. Scott Walker was in power for so long that anything that artistically we really wanted to do or tried to do was never really seen as important. You know, I woke up really early this morning and I was like, “Everyone says Detroit right now has real estate and it’s cheap—what would it cost to go and buy a theatre in Detroit and start trying to make the art we wanted to first of all?”

And I’m going to say this: Divest from Actors’ Equity completely. Because it’s impotent. It has no use at this point. You think you need the union because you don’t want a big corporation or the power dynamic in play, and you need someone to take care of the little guy, right? But if you find producers who aren’t going to take advantage of the little guy, then you wouldn’t need that. Right?

I think the idea is that you can’t rely on the goodness of individual producers. I just heard an arts administrator talk about how if you were to put in place a less hierarchical system, that can keep abusive people out of power, and even drive them away because there would be no place for them to lord it over people. But you need a system that’s bigger than any single person to do that, it can’t just be a hope, and a union is one part of that.

I’m not going to say I’m anti-union because that is not true at all. But the pipeline has been created to the commercial and for-profit theatre; there are so many bodies that are still going to head there. Broadway is going to open and those bodies are going to go there. And we need an accountability entity, especially if we see silence the way that we’ve seen.

I know you were a signatory to the We See You White American Theater document. Is that one entity you think that could hold the industry accountable?

I do a lot of work with Broadway for Racial Justice, and they have an Allied program where they take any organization—it can be a casting director, a school, a theatre company, a general manager’s office—and they basically show them: These are the initiatives, these are the things that we want to do to change our culture. And then anyone who works for that organization is told that if something happens in the space, if something goes wrong, if you have a question about something, don’t worry about going to your employer; you have this other this option, and Broadway for Racial Justice will stand in the gap. They’re your advocate. So you can just do the work that you came there to do. They’re what a union should be doing.

I was just thinking of the Toni Morrison quote about racism being a distraction, taking your precious time and health away from the task at hand, when you just want to do your work.

I would love to do that. But this is where we are.

Rob Weinert-Kendt (he/him) is the editor-in-chief of American Theatre. rwkendt@tcg.org

Creative credits for production photos: Moulin Rouge! The Musical, book by John Logan, directed by Alex Timbers, choreographed by Sonya Tayeh, with scenic design by Derek McLane, lighting design by Justin Townsend, sound design by Peter Hylenski, costume design by Catherine Zuber, hair design by David Brian Brown, makeup design by Sarah Cimino; Fun Home by Lisa Kron and Jeanine Tesori, based on the graphic novel by Alison Bechdel, at Forward Theater, directed by Jennifer Uphoff Gray, Scenic designer by Keith Pitts, lighting designer by Jason Fassl, costume designer by Scott Rott, sound design by James Uphoff, props design by Pam Miles, music direction by Mark Wurzelbacher, choreography by Maureen Janson.